Kirk session records

Introduction

Kirk sessions and their records

Kirk session minutes

Kirk session accounts and other financial records

Deacons’ Court minutes

Managers’ and trustees’ minutes

Registers of baptisms, marriages and burials

Communion rolls and other lists of names

Certificates of transference and other certificates

Chartularies and other legal registers

Population and vital statistics and other statistical returns

Minutes and records of other bodies

Other records among kirk session records

Handwriting in kirk session records and palaeography

Introduction

Kirk sessions are local church courts, held by the Church of Scotland since 1560. Their records comprise one of the most important sources for Scottish history from the sixteenth century until the late nineteenth century. Further information can be found in our guide on church court records.

To search for a particular kirk session go to the Virtual Volumes search or see our guide on using Virtual Volumes.

Kirk sessions and their records

A kirk session is the lowest court in the Church of Scotland, comprising the minister and elders of an individual parish or congregation. In the course of kirk session business, these courts—and in particular the elder appointed to the office of session clerk—produced records documenting their meetings, decisions and transactions.

As well as acting as a church court, kirk sessions had important responsibilities for poor relief and education in Scotland from the late sixteenth century until the late nineteenth century. At local level the amount of poor relief and education activities undertaken by kirk sessions varied from parish to parish and depended on the effectiveness locally of other local bodies, such as heritors and burgh councils.

The key official, in terms of record keeping, was the session clerk, who was usually one of the elders and usually acted as treasurer as well. He was often a local school teacher or lawyer and typically was a clerk to other bodies like parish road authorities, heritors and parochial boards (after 1845). After 1855 he might also have been the local registrar for births, marriages and deaths. This is why kirk session records often contain ‘stray’ records for other local bodies and vice versa.

The ‘standard’ kirk session record was the kirk session minute book. Strictly speaking, this should be a record of the meeting of the kirk session in its role as a court, but since most of a kirk session’s business was transacted at these meetings, minute books often include accounts, poor relief records, lists of parishioners for various purposes, certificates, and some records of baptisms, marriages and burials.

It is important to bear in mind that the record keeping of the kirk sessions was not consistent between parishes, nor between different session clerks. Kirk session records can vary a great deal from parish to parish in detail, quantity, format and structure.

Kirk session minutes

Kirk session minutes are the act books or record of proceedings of the session as a church court. In this sense they are primarily a record of the disciplinary cases heard and any other decisions taken by the session. Minute book entries will typically start with a list of the people who constituted the session (the minister and elders present), known as the sederunt.

However, most kirk session minutes contain much more than this because kirk sessions also had civil responsibilities relating to poor relief and education. Sometimes kirk sessions would keep distinct volumes of records relating to these and other functions, such as account books, registers of baptisms and marriages, and communion rolls. A session clerk might divide a volume into discrete parts (for example, one half of a book devoted to minutes and the other to a burial register), or they might interrupt the minutes proper intermittently to record something else (for example, quarterly accounts or an annual list of baptisms or marriages). More often than not, a session clerk would include these different forms of record within the kirk session minutes themselves by noting everything on a day-to-day basis as session business.

Kirk session minutes for Church of Scotland parishes will frequently contain financial accounts and associated lists of parishioners in receipt of poor relief, though some parishes kept distinct account books, or even account books specifically for the poor’s fund or other purposes.

The minute books of secession churches typically open with an account of the break with the Church of Scotland, for example in the form of a copy of the act of demission and protest and a list of the ministers and elders who signed it. One congregation might keep a combined minute book for the deacons’ court and kirk session, while another might keep distinct minute books for each body.

As well as recording the proceedings of disciplinary cases on a host of moral and social offences, session minutes will often record baptisms, marriages, burials, and notices of people who have either joined the parish from elsewhere or left the parish with a certificate of transference. Minutes might be interspersed with lists of communicants, abstracts of censuses and other statistical accounts of the parish, the formula of subscription signed by the elders, financial accounts, inventories of church property, correspondence (either the original letters or copies written into the minute book), newspaper articles relevant to the church, items relating to the founding or building of a new church (including copies of decreets, constitutions, trustees' minutes, managers’ minutes and presbytery minutes), extracts from wills, and a whole host of miscellanea. As a result, kirk session minute books are a key resource for anyone interested in everyday life in a parish.

Extract from Drainie kirk session minutes, 1711 (National Records of Scotland, CH2/384/2, page 100)

Kirk session accounts and other financial records

The kirk session collected money at church services but it also had other sources of income, such as fines levied in disciplinary cases, fees received for the use of the mortcloth (a decorative cloth hired to cover the coffin at funerals), and occasionally income received from bequests of cash or land left by wealthy parishioners.

The kirk session spent most of its money on regular (weekly or monthly) payments to the poor, but it frequently spent money for other purposes, such as the costs of the annual communion service and administrative costs associated with poor relief and disciplinary matters. In addition, some sessions used their funds to pay for what were really the duties of the heritors, such as the salaries of officials like the schoolmaster and bellman, and the repair and furnishing of the church and school buildings.

Kirk sessions of other Presbyterian churches did not have the statutory civil duties relating to education and poor relief that were imposed on the Church of Scotland, but they sometimes funded schools or engaged in charitable work and had to finance the building of churches, manses and halls.

The treasurer or clerk of the kirk session usually kept accounts for income (often termed ‘collections’) and expenditure (sometimes termed ‘disbursements’ or ‘debursements’). The accounts were commonly recorded in the session minutes, but some parishes kept separate account books. Depending on the whim of each session and in particular each treasurer, specific account books may survive for poor relief, charitable trusts and educational bequests, and other church activities. In account books for the Church of Scotland, poor relief accounts, whether recorded in the minutes or in account book, usually name individual recipients of poor relief within the parish but transient poor were often left unnamed.

If no account books survive for the parish for the period of time you are interested in, look in the kirk session minutes or, in the case of other Presbyterian churches, the managers’ and trustees’ minutes.

Deacons’ Court minutes

Deacons’ Court minutes are records of the Free Church where the role of the Deacons’ Court was to manage the finances of the congregation. In volumes of minutes dating from the Disruption of 1843, when the Free Church was established, it is common to find various notes relating to the split in the Church. These can include lists of names of parishioners who supported the Free Church at the time of its establishment and other documents relating to the construction of a new parish and church building. Deacons’ Court minutes might include information about specific property trusts and bequests but some Free Church parishes kept distinct financial records, managers’ minutes and accounts, trustees’ minutes and accounts, chartularies and other legal and financial records.

Managers’ and trustees’ minutes

In congregations where the secular affairs were not administered by the deacons’ court—most notably in the United Presbyterian and Original Secession Churches—temporal matters were the responsibility of a committee of management. The managers first appear in the late eighteenth century in the context of the first split of secession churches from the established Church of Scotland, and became particularly prominent in the nineteenth century, following legislation for the erection of parishes quoad sacra.

The committees of management—elected from the trustees and occasionally other members of the congregations—were entrusted with the applications for the erection of the new parishes. The minutes record the preparations and application process and usually include a copy of the deed of constitution for the new parish, setting out the managers’ responsibilities. These typically included the management of secular, mainly financial, affairs such as the upkeep of the church buildings, endowments, salaries, the collection of the seat rents and the appointment of some church officers, such as the beadle. Managers had no power in spiritual matters, which lay with the kirk session.

The funds for the new parishes mostly came from charitable bequests. This was especially the case after the introduction into Scots law of the trust disposition and settlement in 1856, which allowed owners to dispose of property to someone other than their direct heirs.

It was the responsibility of a board of trustees to draw up an inventory of the property made over to the church and to administer the liquidation of the bequest. Since the affairs of managers and trustees frequently overlapped, their minutes are often recorded in the same volume, but record keeping was not consistent between parishes, and anyone interested in the financing of the parish and its buildings should look at the records of the relevant kirk session in their entirety.

Registers of baptisms, marriages and burials

The Church of Scotland was responsible for recording the births, deaths and marriages in its parishes before the introduction of statutory civil registration on 1 January 1855. The records of this ecclesiastical registration system became known as the Old Parish Registers or Old Parochial Registers, and they were transferred to the care of the Registrar General for Scotland in 1855, except for some later records which were required in the parishes and submitted later. For further information about these records, please read our church registers guide.

However, many kirk sessions went on recording baptisms and marriage proclamations for their own administrative purposes. These registers can often be found within the kirk session records, either as discrete volumes or as part of minute books, for example. Occasionally pre-1855 registers can also be found in kirk session records, though these are usually copies of registers passed to the Registrar General or else they are part of another volume (such as kirk session minutes). Some other Presbyterian churches also kept registers of baptisms and/or marriage proclamations, which can survive among the kirk session records for these congregations. In most cases, where these survive, they have been indexed and are available to search by individual name under Other Church Registers. You can find more information about these records in our church registers guide.

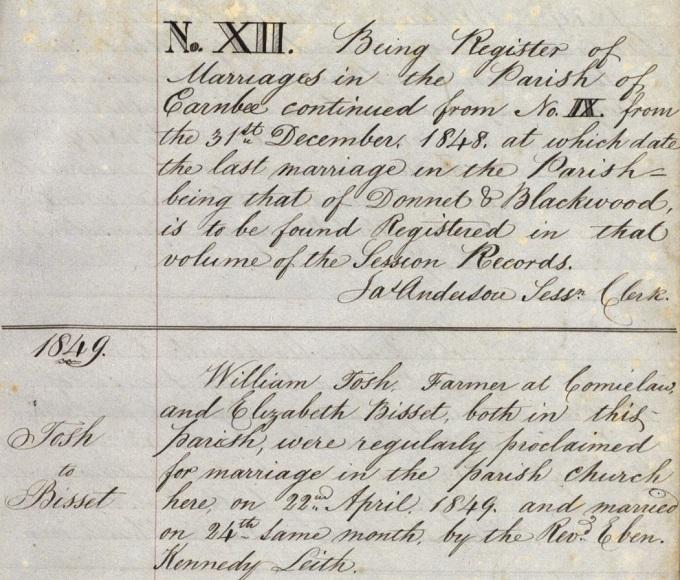

Extract from Carnbee kirk session register of marriages, 1849 (National Records of Scotland, CH2/1032/16, page 1)

Similarly, registers of burials compiled by Church of Scotland parishes prior to the beginning of civil registration should theoretically have been transferred to the Registrar General. However kirk session records often contain burial records of various kinds. There may be a copy kept by a session of a register passed to the Registrar General, or a burial register may form part of a minute book, for instance. There might be a lair register (which records the ownership of burial plots in the churchyard and not necessarily individual deaths), or a mortcloth account book. Mortcloths were large decorated cloths kept by the kirk session, which were hired by the family of deceased persons to cover the coffin during a funeral, or the corpse if a coffin could not be afforded. References to payments for mortcloths, along with payments for coffins or digging the grave of named persons, may appear in kirk session minutes and accounts or in heritors’ minutes or accounts. These can be a useful substitute when burial records are missing or in cases where none were kept.

Until the mid-nineteenth century, burial of the dead was largely the responsibility of the heritors of each parish, carried out almost exclusively in churchyards. In the eighteenth century, some secession churches and other denominations (such as Quakers) opened their own burial grounds. In some towns, separate burial grounds were maintained by burgh organisations, such as merchants or trade incorporations. By the mid-nineteenth century many churchyards were full and burial had become a public health concern. In response, most burghs and parochial boards began constructing municipal cemeteries. Responsibility for all burial grounds within each parish (including churchyards) became the responsibility of parish councils in 1894.

Communion rolls and other lists of names

Communion rolls list members of a church congregation who attended the annual or twice-yearly communion service. They vary in the amount of detail they supply. The most detailed give the names of communicants, their place of residence, occupation, and date of admission to the congregation. The general remarks column can provide further useful information. Other rolls may only give basic lists of names and communion dates, or only record male communicants.

If the communion roll does not list an individual known to have lived in the respective parish, he or she may be recorded in a roll of adherents, if this was kept by the parish. A list of communicants can sometimes also be found in kirk session minutes, especially in the case of newly-formed quoad sacra parishes and secession church parishes.

Communion rolls vary in the amount of detail they supply, but the most detailed give the communicant's place of residence, occupation, date of admission to the congregation and where he/she had come from. The general remarks column can provide further useful information.

Until the second half of the twentieth century, parishioners could rent their pews in the church, which guaranteed them a particular seat. Seat rent books usually recorded the renter’s name, the sum paid and the position of the seat, thus indicating the person’s standing in the community. Since renting a pew was a privilege, these records do not provide a full list of parishioners, nor do they always include women.

Some congregations did not keep separate seat rent books. In these cases, lists of seat renters might be included in the minute or account books of the kirk session or, in the case of secession churches, in the minutes or accounts of the managers.

In addition to communion rolls and registers of baptisms, marriages and burials, kirk sessions habitually produced other lists of parishioners, such as male heads of household, rolls of adherents or parish population surveys.

Following legislation in 1834 concerning the calling of ministers to vacant parishes, kirk sessions were required to draw up lists of male heads of families in their congregations. They supply few details other than names and residences but they are nevertheless a useful guide to the whereabouts of families in the decade before the 1841 census.

Rolls of adherents list parishioners or regular worshippers permanently connected to the parish, but not partaking in the communion. Adherents were often young people working towards full membership by attending Bible classes. Adherents’ rolls typically supply dates of baptism, and the remarks column can provide useful information about the adherents’ occupations and their families’ movements.

In many cases parish population surveys were a by-product of the gathering of population and vital statistics for official publication, but some parishes appear to have compiled lists of families or persons in the parish for other purposes. These lists might include individuals’ names, places of residence, occupations, number of dependants and other details. However, as with many types of record kept by kirk sessions, the content varies considerably from parish to parish.

Not every kirk session produced or preserved lists like these. Apart from the list of heads of households, these records were not statutory, so the format and details they contain will vary between parishes. Where separate lists of parishioners do not exist, it is worth checking the kirk session minutes.

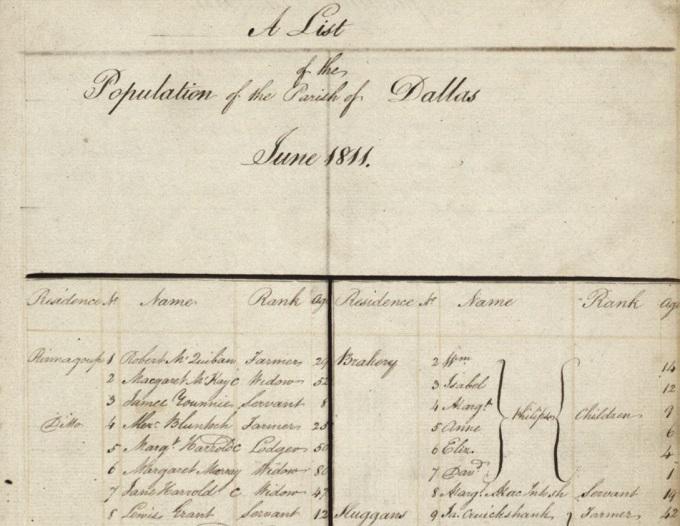

Dallas kirk session, extract from list of population of parish, June 1811 (National Records of Scotland, CH2/1129/2, page 25)

Certificates of transference and other certificates

When communicants (members of a church) moved to a new parish, they could be issued with certificates of transference by their old parish, stating that they were in full communion with the Church of Scotland or a secession church at the time they left. This would allow them to become members of their new parish church immediately.

There is some variation in the wording of the certificates: most simply state the date, the person’s name and the fact that they left the parish in full communion with the Church. Some, however, give more of each communicant’s personal details.

Relatively few certificates of transference survive and it is rare to find a large collection of them together. However, you may find the occasional one or two at the back of a communion roll or perhaps a volume of kirk session minutes. Kirk session minutes often record the issuing of a certificate to a parishioner who had moved or note that a new parishioner had submitted a certificate from another parish. Most certificates of transference on this site date from the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Chartularies and other legal registers

Chartularies are volumes containing copies of title deeds to property, deeds and other legal documents. Kirk session records sometimes contain chartularies and other registers or lists of legal documents. In some cases these will have been drawn up at the time of the election of a new minister, when an inventory of church property in the hands of the outgoing minister was required. In other cases they were compiled by the treasurer or session clerk in order to keep track of funds and property. Some parishes kept separate inventories of bonds. These recorded loans to merchants and landowners, which wealthier parishes used would make to avoid keeping large sums of cash on church premises and to provide a steady income. Others compiled chartularies or registers to record specific charitable bequests of property (or the revenues from property if the land itself was not conveyed to the church) left to the church for the purposes of education or poor relief. The reason for keeping such a volume and its likely contents might be obvious from the description, but in many cases it is hard to be completely sure without reading through the contents.

If the kirk session records for a particular parish do not contain separate records like these, it can be worth looking for this information in the kirk session minutes or accounts, or in heritors’ records.

Population and vital statistics and other statistical returns

Occasionally, population and other vital statistics, such as the number of births, marriages and burials occurring in the parish, survive among kirk session records. In most cases, these are transcripts of statistics which were supplied to the authors of the Statistical Accounts (1791–1798 and 1834–1845) and the censuses (1841–1901). As these statistics seldom include individuals’ names, they are of limited use to genealogists, though they may be of interest to researchers examining social and economic changes in the locality and their impact on the structure of the parish population. Statistics were not always kept separately and are sometimes included in the kirk session minutes.

Minutes and records of other bodies

The records of kirk sessions frequently contain minute books and other records relating to a wide variety of bodies associated with the church and its members. These can include committees and societies set up for special purposes within the parish (such as organ committees, Sabbath school associations, women’s groups, hall committees, literary societies and so on). The records of charitable trusts may also be included.

Kirk sessions acted in conjunction with other civil and ecclesiastical bodies within the parish in providing education, poor relief and public health. In many cases the session clerk might also serve as the clerk to bodies such as the heritors, the parochial board and road trustees. The clerk might use a single book to record the minutes of more than one body, for example kirk session and heritors’ minutes, or the clerk might keep a second copy of the minutes of, say, a parochial board, on which the kirk session was represented. Alternatively, a volume might begin as the minute book of a joint committee of the kirk session and heritors of a parish but become (at some point after 1845) the minutes of a parochial board.

This explains also why kirk session minutes sometimes appear within the heritors’ or parochial board records of the relevant parish, especially during the transferral of poor relief, education and other civil functions from church to local civil authority control in the period 1845–1894.

In most cases, the purpose of the records concerned should be apparent from the description, but records of this type are quite diverse, so you might need to read the first few pages of a minute book to decide why the records were kept by the session clerk and whether the content of the records concerned are of interest to you.

Other records among kirk session records

Among the records of kirk sessions, it is possible to find unusual items, such as correspondence, loose legal papers, year books, annual reports, petitions and other working papers accumulated for the purpose of conducting the congregation’s affairs.

It is difficult to classify many of these coherently, but their descriptions are usually self-explanatory. Some kirk session clerks preserved the diaries or journals of ministers. Their style and informational value vary considerably. In most cases, they simply record a list of sermons preached and other commitments of a purely professional nature. Occasionally they also include references to the minister’s private life and family, the health of a parish and medical matters, and the weather. In most cases the diary or journal survives because it is part of a composite volume of records (for example, the minister might have used the last few pages of a minute book as a personal journal).

Handwriting in kirk session records and palaeography

Although kirk session minutes are a form of court record, the amount of legal terminology is small and the handwriting is relatively easy to read by most researchers back to the late eighteenth century. Prior to that (as with other early modern records) the handwriting can be challenging but, once the researcher has undertaken a small amount of palaeography tuition, kirk session records are among the easier types of early modern records to use. If you are new to research using original records prior to the late eighteenth century, you can find help in our guide on reading older handwriting, the Scottish Handwriting resource and a glossary of abbreviations, words and phrases.