Reading older handwriting (palaeography)

Background information

If you have problems reading a document, this guide may help you get the most from your research. To improve your research using manuscript historical records you need to study a few things:

- diplomatic (knowledge of the forms that records take, for example, the form of a testament)

- palaeography (the ability to read older forms of handwriting)

- vocabulary (the specialist vocabulary in certain records, for example, sums of money, agricultural produce and weights and measures)

- Scots language (the spelling, grammar, and abbreviations in the older Scots tongue)

Secretary hand

This website features manuscript records from the early sixteenth century to the twentieth century. During that time handwriting in Scotland (as elsewhere in Europe) changed quite radically. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the clerks, who compiled these records wrote mainly in a form of handwriting known as secretary hand, many of whose letters were different from the letters we know today. However, clerks invariably knew other forms of handwriting (such as italic) and frequently jumbled up handwriting styles, so that a line of text might include secretary hand letters, italic letters, and other letter styles. From the mid eighteenth century handwriting gradually changed to become modern handwriting. However, the change was not consistent everywhere. Each clerk had a different style (and a different standard of writing clarity). Even nineteenth century handwriting can be difficult to read.

The following examples from testaments illustrate the change in handwriting over the centuries:

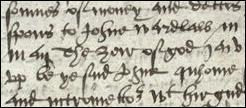

In this first example, the handwriting writing looks odd because many of the letters are in their secretary hand forms (for example, a, b, c, d, e, g, h, k, r, s, and t). Other problems are Latin numerals, archaic letters (the yogh and the thorn), Scots vernacular words, phonetic spelling, abbreviations, and interchangeable letters (at this time the letters u, v and w were variations of the same letter, as were the letters i and j).

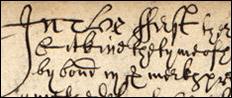

In this second example, some letters are recognisably secretary hand, but the writing is not as neat as the previous example. Many letters are cursive (either untidy versions of secretary hand, italic, and other writing styles, or forms of the writer's own invention). Other problems include elaborate letters which interfere with other letters or make several words look like one continuous word).

The handwriting in the last example is very neat, but not all handwriting from this period is easy to read.

Further reading

Use the record guides to understand the form of documents such as valuation rolls and wills and testaments. Consult our guides on agricultural produce and livestock, dates, numbers and sums of money, unfamiliar words and phrases, and weights and measures.

Search our glossary for help with abbreviations, legal terminology, occupations and other unfamiliar words. Consult the Dictionary of the Scots Language for additional help with Scots words.

For further help with palaeography visit the Scottish Handwriting resource in particular the testaments tutorial and the palaeography posers organised by different record types.

Scottish Handwriting 1500-1700: A self-help pack, Edinburgh 2022, is a step-by-step guide to reading the handwriting of Scottish documents dating between 1500 to 1700 using facsimiles, mainly from the National Records of Scotland's (NRS) archives. This is an updated version of the original 1994 kit, created in partnership with the NRS and the Scottish Records Association (SRA).

The updated kit includes higher quality colour images of the records, updated bibliography, and the inclusion of web sources for further practice and reading. Types of documents studied are: wills and testaments, bonds, personal letters, burgh records and High Court minute books.

A physical copy can be purchased from the ScotlandsPeople Online Store. A free digital version of the handwriting pack is available to download from the Publications page on the NRS website.