Surnames

How to use surname search options

Background information

This guide is about surnames and how to search effectively by surname in records that are indexed by personal name. It gives you some background on the development of surnames in Scotland, tells you common reasons why surnames have variations or the spelling of surnames are sometimes not what you might expect. It gives you advice on how to use surname search options to improve your searching.

Why surname spelling varies

The way surnames were written in different records varied and, when searching for a person in our indexes, the spelling might differ from what you expect. This can be due to one or more of the following factors:

- transcription error during indexing

- misspelling, phonetic spelling or other misinterpretation by registrars and clerks

- deliberate or accidental misrepresentation by informants

- surname variants

- the family members may have altered their surname after emigration from Scotland, or anglicised the name on arrival in Scotland

- families from the Highlands and Western Isles may have anglicised their Gaelic surname, for example, MacIan to Johnston.

How to use surname search options

If you are unsure of the spelling of a surname, or you suspect the name may have been recorded differently, you can use the 'surname search options' to improve your search. Here are the ways you can use the search options:

Leave the surname field blank

You can leave the surname field blank and search by using only a forename or other search fields.

Exact names only

If you select 'Exact names only' it will return all entries that contain the whole search name, so a search on the surname DOUGLAS, for example, will return all DOUGLAS entries. Hyphenated names such as MONTAGU-DOUGLAS and DOUGLAS-HOME are also returned. Variations in the spelling of the search name and partial matches (where the search name is included in a longer name), for example DOUGLASS, will not be returned.

Fuzzy Matching

Fuzzy matching compares each word in the name searched for with each word in the names in the index using the Levenshtein distance formula. A score of half the number of letters in the word or greater is considered a match. The Levenshtein distance is a metric for measuring the amount of difference between two sequences (the so-called edit distance).

Names that begin with

If you select 'Names that begin with' it will return all matches which begin with the letters searches, and DOUGLAS, for example, will return DOUGLASS.

Phonetic matching

Phonetic matching is an attempt to deal with variations in spelling the same word, especially personal names, based on the combination of letters representing sounds. It relies on a phonetic algorithm to suggest possible variations of the same word. On the ScotlandsPeople site we use the Beider-Morse phonetic matching system (sometimes abbreviated as BMPM). For more information on this see the Steve Morse website.

Wildcards allowed

If you select 'Wildcards allowed' it allows you to use symbols to find variations in the characters within a word.

- Substitute the asterisk (*) or percentage sign (%) for zero or more characters

- Substitute the question mark (?) or underscore (_) for one character only

These characters can be substituted anywhere in the surname or forename and can be employed in various combinations. However, you should try to be as specific as possible in your use of wildcards to avoid returning unnecessary amounts of data. Here are some tips about using wildcards:

- A wildcard search on a surname will still return entries with extra forenames and those where the chosen forename appears as a second or subsequent forename.

- Where a surname may have been recorded with a spelling involving only one change of letter, for example, SMITH recorded as SMYTH or CALLISON recorded as CALLISON, you may find it useful to employ the question mark wildcard (?) to locate them.

- Be careful in your use of the asterisk wildcard (*) at the end of a surname. For example, BRYD* would locate any names beginning with BRYD, such as BRYDON, BRYDAN, but also BRYDENTON, BRYDALL, and BRYDSON.

- Where a Mc surname may have been recorded as Mac, or vice versa, use the asterisk wildcard (*) to locate it. For example, M*CDONALD or M*CDONALD will find both MCDONALD and MACDONALD entries.

- You can use multiple wildcards in a single search, for example, searching on M*CGIL*V?R*Y will return many variants of the surname; MCGILVERY, MCGILLVERY, MCGILIVARY, MCGILLIVARY, MCGILLIVERY, MCGILLIVERAY, MCGILVARAY, MCGILVAREY, MCGILVARY, MCGILVEREY and so on, together with the Mac versions.

- Entries in the surname field must contain a minimum of two characters, but neither of these can be a wildcard. For example, M*, *M, will not be accepted, but M*M, MA*, or *MA are all accepted.

Surnames in Scotland

Permanent surnames began to be used in Scotland around the 12th century, but were initially mainly the preserve of the upper echelons of Scottish society. However, it gradually became necessary to distinguish ordinary people one from the other by more than just the given name and the use of Scottish surnames spread. In some Highland areas, however, fixed surnames did not become the norm until the 18th century, and in parts of the Northern Isles until the 19th century.

The influences on Scottish surnames are many and varied and often more than one has resulted in the surname that we know today. It is therefore very difficult to attribute sources for surnames with complete certainty, although there are many books on the subject of surname origins that attempt to do just that. Here are just some of the elements thought to have contributed to present day surnames:

Foreign influences on Scottish surnames

External influences have played a crucial role in the shaping of surnames in Scotland. The migration of the Scots from Ireland into the Southwest in the 5th century, nurturing the spread of Gaelic language and culture, the influence of the resident Picts, the establishment of the Britons in Strathclyde, and Anglian immigrants in Lothian and the Borders, all contributed to the melting pot of surnames that we have today.

The Norsemen, through their seasonal raiding and subsequent colonisation of the Western and Northern Isles, left behind aspects of their heritage and language that endure not least in the surnames of these areas, for example Gunn is originally derived from the Norse and appears in significant numbers in the North of Scotland. Scandinavian influence can be seen in other parts of Scotland too, for example, Thorburn is an old Norse name found in the Scottish borders and around Edinburgh.

Norman influence filtered into Scotland after their invasion of England, and was actively encouraged by Scottish kings. Anglo-Norman nobles acquired grants of land around Scotland and introduced the feudal system of land tenure. For example, Robert the Bruce was a descendant of Robert de Brus who fought with William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings. Bissett, Boyle, Colville, Corbett, Gifford, Hay, Kinnear and Fraser are all originally Norman names, which first appeared in Scotland in the 12th century. Menzies and Graham are recognised Anglo-Norman surnames also first seen in Scotland at this time.

Continuing into more recent times, the effect of Irish immigration during the 19th century can be seen in the surnames now in use in Scotland, for example Daly or Dailly is an Irish name derived from O’Dalaigh and concentrations can be found in areas where Irish immigrants settled, around Glasgow and Dundee. This is borne out in the records, with very few people of that surname appearing in the OPRs, but significant numbers appearing in the statutory registers. Names like Docherty and Gallacher, now quite common in Scotland, are also relatively recent additions.

Location-based surnames

Many of the first permanent surnames are territorial in origin, as landowners became known by the name of the lands that they held, for example Murray from the lands of Moray, and Ogilvie, which, according to Black, derives from the barony of Ogilvie in the parish of Glamis, Angus. Tenants might in turn assume, or be given, the name of their landlord, despite having no kinship with him.

Occupational surnames

A significant amount of surnames are derived from the occupations of their owners, Some of these are obvious, for example Smith, Tailor, Mason, and others might be less obvious for example Baxter (baker), Stewart (steward), Wardrope (keeper of the garments of a feudal household) and Webster (weaver). Cordiner, Soutar and Grassick are all derived from shoemaker, the latter being from the Gaelic for shoemaker, greusaich.

Patronymics

Many Scottish surnames originated in patronymics, whereby a son’s surname derived from the father’s forename, for example John Donaldson’s son might be Peter Johnson, whose son might be Magnus Peterson, and so on. Patronymics present something of a challenge for the family historian in that the surname changed with each successive generation.

This practice died out in Lowland Scotland after the 15th century, as patronymic surnames became permanent family names. It persisted, however, in the Highlands and Islands well into the 18th century (see Mac surnames) and in the Northern Isles until the 19th century.

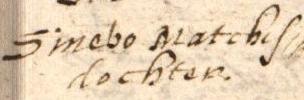

The system was applied to daughters’ names too, with the girl adopting the father’s forename with daughter applied to the end of the name. The daughter suffix was habitually abbreviated in the records, for example, Janet Adamsdaughter becomes Janet Adamsdaur, or Adamsdr or Adamsd. An entry from the Lerwick OPR in 1734, neatly illustrates the effect of patronymics with the birth/baptism of William Laurenceson to Laur. Erasmuson and Katharine Nicollsdr.

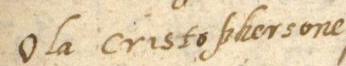

Ola Cristophersone

Sinevo Matchis dochter

Mac Surnames

Mac is a prefix to surnames of Gaelic origin meaning son. For example, Macdhomhnuill translates to Macdonald, meaning son of Donald.

You may come across the feminine version Nc, an abbreviation of nighean mhic or daughter of Mac, attached to a woman’s surname, and sometimes further abbreviated to N'. There are many examples in the old parish registers, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, for example Ncfarlane, Ncdonald, Ncdearmit, Ncfee, but there are only isolated examples by the early 19th century.

In earlier records, a person might be known not only by the father’s name but also by the grandfather’s name. As such, you may come across the use of Vc, meaning grandson or granddaughter, for example, in 1673 Dugall Mcdugall Vcean (Dugall, son of Dugall, grandson of Ean) married Marie Camron or NcNdonochie Vcewn .

Some Mac surnames originated in occupations, for example Macnab (son of the abbott), Maccosh (son of the footman), Macmaster (son of the master or cleric), Macnucator (son of the wauker or fuller of cloth), later anglicised Walker. Others derive from distinguishing features, for example Macilbowie (son of the yellow haired lad), Macilchrum (son of the bent one). Yet others contain vestiges of Norse influence, for example Maciver (son of Ivar, a Norse personal name), since the Mac prefix was not the exclusive preserve of the Gaels, being adopted in some cases by the Norsemen and by some Lowland Scots, particularly on the Highland periphery, for example Macgibbon, Macritchie.

Many Mac surnames no longer in use such as Macolchallum were abandoned because they were too difficult to pronounce, corrupted over the years by phonetic spelling, or anglicised.

Mac surnames were also written as Mc, Mhic, or M’. Mc/Mac surnames are indexed separately in the database, but it is very common to find the same person’s surname registered as Mc in one record and Mac in another, so you should always check both. Using the asterisk wildcard (*) will return both versions in one search, for example M*CDONALD will retrieve both MCDONALD and MACDONALD entries.

Ronald m[a]cdonald v[i]c Ean

![T[estament] d[ative] Janet Fraser alias nein donill vic robie](/sites/default/files/styles/maximum_size/public/2020-04/topicSurnames5.jpg?itok=_cGtmMye)

T[estament] d[ative] Janet Fraser alias nein donill vic robie

Please note that some index entries have an unfortunate gap between the Mc/Mac and the rest of the name. Staff will correct them as they come across them and any customers who spot these should report them to us as index errors. To try to account for these in search results, customers should try search options such as wildcards.

Clan-based surnames

It is a common misconception that those who bear a clan surname are automatically descended from a clan chief. The ability of a clan to defend its territory from other clans depended greatly on attracting as many followers as possible. Being a member of a large and powerful clan became a distinct advantage in the lawless Highlands and followers might adopt the clan name to curry favour with the Laird, to show solidarity, for basic protection, or because their lands were taken by a more powerful neighbour and they had little option! Yet others joined a clan on the promise of much-needed sustenance.

Conversely, not all members of a clan used the clan surname. When Clan Gregor was proscribed in 1603, many Macgregors were forced to adopt other surnames for example Grant, Stewart, Ramsay. When the clan was again proscribed during the 18th century, Rob Roy Macgregor adopted his mother’s name Campbell. Once the ban was lifted in 1774, some reverted to the Macgregor name, but others did not.

Effects of Emigration and Migration

Many emigrants from Scotland changed their names on arrival in their new country, as did many people from the Highlands and Islands who migrated to the Scottish lowlands in search of work. Shortening or dropping the prefix Mc or Mac, or anglicising a Gaelic surname, or indeed changing the surname altogether for a similar sounding English one, which would be easier to pronounce and would conceal one’s origins, were quite common occurrences. Thus the Gaelic surname Macdonnchaidh or Macdonachie becomes Duncanson, Macian becomes Johnson, Macdonald is anglicised to Donaldson, Macilroy becomes Milroy, and Maccowan becomes Cowan. The Gaelic Mac Ghille dhuibh, or son of the black lad, seen in the surnames Macilduy, Macildue and Macildowie, translates to Black. Gilchrist, a gaelic name meaning servant of Christ, might be anglicised to Christopher. Illiteracy might, however, engender a change of surname by default, giving rise to weird and wonderful variants, for example Maclachlan recorded as Mcglauflin.

To-names or T-names

To-names or T-names meaning 'other names' or nicknames, were prevalent particularly in the fishing communities of North East Scotland, but were also seen in the Borders and to a lesser extent in the West Highlands.

In those areas where a relatively small number of surnames were in use, T-names were tacked on to the name to distinguish individuals with the same surname and forename. The nickname may have referred to a distinguishing feature or be the name of the fishing boat on which the person was employed. These T-names have made their way into the records. For example, amongst the numerous John Cowies of Buckie can be found fisherman John Cowie Carrot who married Isabella Jappie of Cullen in 1892. Was this perhaps a reference to the colour of his hair?

The T-name appears on a statutory results page in brackets in order to distinguish it from a middle name for example James (Rosie) Cowie, James (Bullen) Cowie, Jessie (Gyke) Murray, and may be designated in inverted commas on the image of the actual entry.

Early spellings may vary from later ones

You may find in older records that Quh and Wh are interchangeable, for example White might be recorded as Quhit, Quhytt, Quhyitt, Quhetit, Quheyt, Quhyte, and so on. Macwatt may be written as Macquhat. Ch or ck may be dropped from the end of a surname for example Tulloch is rendered as Tullo in many earlier records, Tunnock as Tunno. It is very common to find an e added to the end of surnames in earlier records (for example, Robertsone for Robertson, Pearsone for Pearson), or that w and u are interchangeable (for example, Gowrlay for Gourlay or Crauford for Crawford), or u being inserted to surnames ending in on or one (for example Cameroun for Cameron, Robertsoun or Robertsoune for Robertson). Names like Morrison may be rendered as Morison, likewise Ker for Kerr. A surname ending in y might be replaced with e as in Murray and Murrie. The letter i might be replaced with y as in Kidd and Kydd.

Further reading on surnames

For further information on the origins of Scottish surnames, the following books are helpful:

Black, George F, 'The Surnames of Scotland: their origin, meaning and history' (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 1999, Reprinted 2004, first published by the New York Public Library, 1946) - viewed as the principal work on surname origins.

Dorward, David, 'Scottish Surnames' (Glasgow: HarperCollins, 1995) – a pocket-sized book, which concentrates on surnames currently in use in Scotland. It is particularly useful for its information on surname concentrations.