The Scottish Witchcraft Act

Witchcraft in Scotland

Prosecution of witchcraft cases

The case of Alison Dick and William Coke

The decline of witch-hunting

The repeal of the Scottish Witchcraft Act

Further reading

On 19th November 1633, Alison Dick and her husband William Coke were executed for the crime of witchcraft in Kirkcaldy. Fascinating details of their case are revealed in the recently released kirk session records from the National Records of Scotland (NRS) on ScotlandsPeople.

Their story is told below, but first a brief history of witchcraft in Scotland from the 16th to 18th centuries: why and how did witch-hunting take place and what was its impact on society?

The Scottish Witchcraft Act

Over 450 years ago the Scottish Witchcraft Act came into force in 1563 and was not repealed until 1736. Under this Act, both the practice of witchcraft and consulting with witches were capital offences. (The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland, A1563/6/9. Date accessed: 14 July 2021.)

In England, the Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act in 1542, though it was repealed five years later. It was restored by a new Act in 1562. A further law was passed in 1604 and this together with the 1562 Act transferred the trials of witches from the church to the ordinary courts.

The Scottish Witchcraft Act was part of the more general movement for social and behavioural regulation following the Reformation in 1560 which changed the dynamics between the clergy and common people. A crucial element that developed in the definition of the crime of witchcraft by the church and state was a pact with the Devil. It was believed that witches were not only sorcerers but Devil-worshippers; they were both criminals and heretics and therefore a deadly threat to Godly society. (Stuart Macdonald, ‘The Witches of Fife: Witch-hunting in a Scottish Shire, 1560-1710’, pages 3, 143).

During the time the act was in force from 1563 to 1736, the vast majority of prosecutions took place within a relatively short period from 1590 to 1662. Even within this time span, the rate of witch-hunting was not uniform, with flashes of intense hunting ‘panics’ first recognised by the historian Christine Larner. These collectively lasted only around six to seven years but accounted for more than half of all known Scottish witchcraft cases.

Witchcraft in Scotland

The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft database, compiled by the University of Edinburgh, is the most comprehensive resource and easiest starting point for researching witchcraft in Scotland. According to this database, there were nearly 4,000 people known to have been formally accused of witchcraft in Scotland and over 3,000 of these by name.

Although the database does not claim to include all instances of accusations of witchcraft, as a lot of the documentary evidence is missing and what has survived is difficult to find, it lists the relevant records for each, many of which are held by the NRS.

Women, especially the poor, middle-aged or elderly, who lived on the fringes of the Godly society, were the main suspects. They were not in a position of social and political power and were also seen as weak and susceptible to the temptation of the Devil.

Painting of ‘A Witch’. Unknown artist

Credit © Wellcome Collection. Public Domain

Prosecution of witchcraft cases

Witchcraft was a serious crime beyond the regular jurisdiction of the local courts, so the local prosecutors had to negotiate with the central government in Edinburgh.

- The local church courts (the kirk sessions and presbyteries) were often the first place where people complained about their neighbours’ witchcraft. The church courts would require the accused to appear and account for themselves, interrogate them and gather evidence from neighbours. However, they had no criminal jurisdiction and had to pass the case on for a criminal conviction.

- The Privy Council, committee of estates or Parliament were central bodies that did not hold trials themselves but issued ‘commissions of justiciary’ authorising other people to hold trials.

- The High Court of Justiciary was the highest criminal court, usually held in Edinburgh, and the Circuit Court a travelling version of this.

- Other local courts such as the sheriff courts and burgh courts, also tried cases although witchcraft was a serious crime and often outside their jurisdiction.

- Lastly, there were ad hoc local criminal courts held under commissions of justiciary issued by central government which were usually convened to try just one individual for a crime.

Most Scottish witches were tried in the local criminal courts, although you will also find cases in the kirk session minutes and the High Court records. Few records of the ad hoc courts held under commissions of justiciary survive, although there is usually a record of the issue of a commission in the Privy Council records.

The evidence used in trials usually consisted of: confession; neighbours’ testimony; other witches’ testimony and searching for the Devil’s mark. The Devil was believed to mark his followers when they made a pact with him, as a parody of Christian baptism. In order to locate this mark - either a visible bodily blemish or an insensitive spot - a physical search was undertaken of the suspect's body. The insensitive spot was discovered by pricking with pins, sometimes by the interrogators themselves or by itinerant professional witch-prickers.

Woodcut of witches dancing in a circle with the Devil. The History of Witches and Wizards, 1720

Credit: © Wellcome Library. Reproduced under Creative Commons license by 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The enforcement of the Scottish Witchcraft Act had deadly or life-changing consequences for those accused. Around 2,500 people were executed, though contrary to popular belief, those condemned to be executed as witches were very seldom burned alive. More usually they were strangled at the stake and then their bodies burned.

For those people who were not executed, other punishments included: banishment, being outlawed, excommunication, imprisonment, and there is even one known case of public humiliation. A small number were acquitted whilst others fled.

At least 1,500 people who were formally accused of witchcraft did not result in a conviction or indeed a trial because of insufficient evidence. However, if an individual was accused of witchcraft, and the charges were later refuted or they were let off, it was still harmful for their reputation. They could find themselves facing an accusation and/or a charge at a later date, as found in the case of Alison Dick and William Coke, one of the most complete witchcraft cases for Fife.

The case of Alison Dick and William Coke

Within the Kirkcaldy kirk session minutes for 1633, amongst the usual business of the session (giving and collecting money for the poor, public repentance for adulterous behaviour and drinking on a Sunday in dubious circumstances); we find the case of Alison Dick and her husband William Coke who were accused of witchcraft.

It took place just after a significant period of witch-hunting in Scotland from 1628 to 1631 but seems to have arisen as a result of accusations made locally rather than part of a specific witch-hunt.

Alison was first investigated as a witch as early as 1621. Kirkcaldy kirk session noted her appearance before them ‘accusit of sundrie poynts of witchcraft’, which she denied, and the ‘mater remitted to farther proban’.

Alison Dick denies the accusation of witchcraft, Kirkcaldy kirk session minutes, 13th February 1621

National Records of Scotland, CH2/636/34, page 67

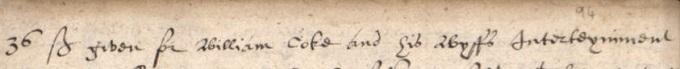

Two years later on 13th May 1623, the session noted expenses of 36 shillings ‘for William Coke and his wyfs Interteyniment’

Note of William Coke and his wife’s internment, Kirkcaldy kirk session minutes, 13th May 1623

National Records of Scotland, CH2/636/34, page 94

Their imprisonment was not necessarily to do with witchcraft but related to the way they seemed to treat others in their community. It is recorded in the Kirkcaldy Burgh records that they were released the following month upon a bond of caution due to insufficient evidence. (Macdonald, ‘The Witches of Fife’, page 145).

Alison and her husband had been publically displayed as troublemakers in the community and their reputations tarnished. Ten years later, the situation escalated and events took a dark turn. They found themselves before the kirk session again, but this time they were accused as witches.

Once someone was accused of witchcraft, the kirk session would seek other accounts to back up the reports. Alison and William were a quarrelsome pair and in this case there was plenty of evidence forthcoming as they had caused trouble between themselves, their family and neighbours.

On 17th September 1633, Alison appeared accused of activities ‘tending to witchcraft’. Although she denied the charges, witnesses came forward with evidence. Alison and her husband were overheard arguing in which he accused her of sinking ships and they both said that each other would have been better off dead. (NRS, CH2/636/34, page 280).

The kirk session met again the following week on 24th September and the focus moved from the quarrelling couple to the acts they were alleged to have committed, from cursing their neighbours and allegedly causing them ill-fortune, and also highlighted the tensions within the couple’s family. (NRS, CH2/636/34, pages 280-282).

Once the session had collected evidence, the person accused of witchcraft, in this case Alison Dick, could be imprisoned and guarded. During imprisonment they could be questioned by the kirk session in an attempt to secure a confession.

On 8th October 1633, Alison confessed to making a pact with the Devil. She portrayed herself as the victim and her husband as the villain of the piece.

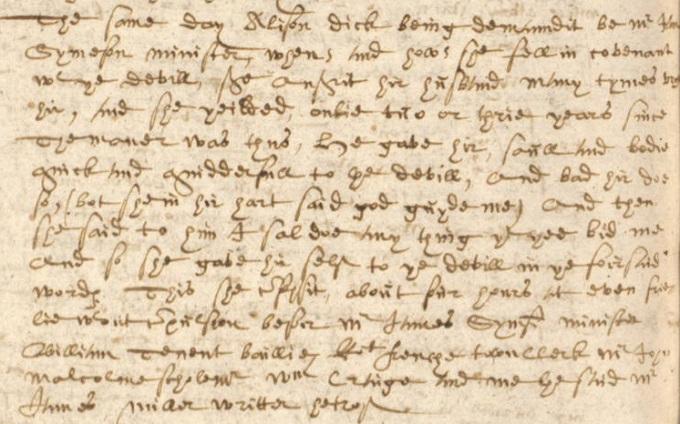

Alison confesses to making a pact with the Devil, Kirkcaldy kirk session minutes, 8th October 1633

National Records of Scotland, CH2/636/34, page 284

‘The same day Alison Dick being demandit be M[iste]r James

Symeson minister, whens and hows she fell in covenant

w[i]t[h] [th]e devill she ans[e]rit hir husband many tymes vrged

hir, and she yielded onlie tuo or thrie years since

The maner was thus, He gave hir, soull and bodie

quick and quidderfull to the devill and bad hir doe

so, (bot she in hir hart said god guyde me) And then

she said to him I sal doe anything [tha]t yee bid me

And so she gave hir self to [th]e devill in [th]e foirsaid

words This she c[on]fessit about four hours at even frie-

lie w[ith]out c[om]pulsion befoir M[iste]r James Syms[on] minister

William Tenent baillie R[ober]t frenche town clerk Mr John

Malclome Scholem[aste]r W[illia]m Craige and me the said M[iste]r

James mi[ll]ar written heirof’

The kirk session kept a careful record in the minutes of Alison’s incarceration in the church steeple from 2nd October onwards. On 15th October, it is recorded that soldiers were paid 14 shillings to keep watch over her and keep her awake: ‘for Alison Dickes Interteyniment who is ordaned to be wakeit heirafter.’ (NRS, CH2/636/34, page 284). No reference is made to William’s confession or detainment in the minutes.

After Alison’s confession, evidence continued to be collected which painted her in a very different light to the victim she purported to be in her confession. She was seen a dangerous quarrelsome woman not to be crossed.

On 15th October, Cristian Rannaldsone recounted that she had sold a house to Alison but her husband ‘said he wald not have the devil to duell above him in the clois’ and struck up the door and put forth the chimney she had put in it. Alison then told Cristian that her husband would set sail soon and lose his stock which came to pass when David Whyts’ (the ship master) ship was lost with stock owned by Cristian’s husband on board. (NRS, CH2/636/34, page 284).

More evidence was gathered against Alison on 22nd October. According to Kathren Wilson, Alison had visited her and Janet Whyt and begged for money from Janet. Alison then complained that she didn’t give her very much and proceeded to curse and urinate at their meal cellar door. As a consequence, the meal never lasted in the cellar. Furthermore, a horse they owned was said to be bewitched and died having proved itself useless. (NRS, CH2/636/34, page 285).

The testimony of Alison and William was concluded on 29th October when the final evidence in the case was collected. Prior to this, on 15th October Alison affirmed her confession and also asked for forgiveness.

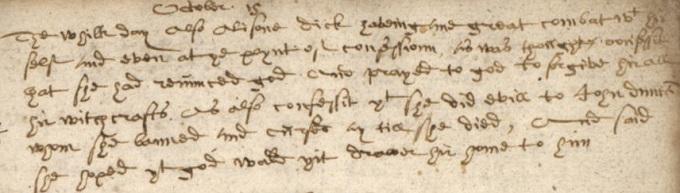

Alison affirms her confession and asks for forgiveness, Kirkcaldy kirk session minutes, 15 October 1633

National Records of Scotland, CH2/636/34, page 285.

‘October 15

The whilk day also Alison Dick haveing ane great combat w[i]t[h] hir

self and even at [th]e poynt of confessioun as was thowght confessit

that she had renunced god And prayed to god to forgive hir all

hir witchcrafts As also confessit [tha]t she did evill to John Dunca[n]

when she banned and cursed ay till she died, And said

she hoped [tha]t god wald yit drawer hir home to him.’

The church courts moved quickly during Alison and William’s case. Two days after Alison’s affirmation of her confession, Kirkcaldy presbytery were informed of the situation (NRS, CH2/224/1, page 115). By the 29th, Robert Douglas was appointed to go to the Archbishop with the information that had been gathered. (NRS, CH2/636/34, page 286.)

After the confession before the church courts, a commission would be sought from the Privy Council to put the accused on trial and then, if guilty, they would be executed. For Alison and William’s case, a commission was sought from the Privy Council and issued on 8th November 1633. [Macdonald, Witches of Fife’, page 150). By 14th, the presbytery were informed that they were to go to trial (NRS, CH2/224/1, page 116). The records of the trial have not survived but it is likely to have taken place soon after, as the couple were burned as witches on 19th November 1633.

Alison Dick and her husband William Dick are burnt for witchcraft, 19th November 1633

National Records of Scotland, CH2/636/34, page 287.

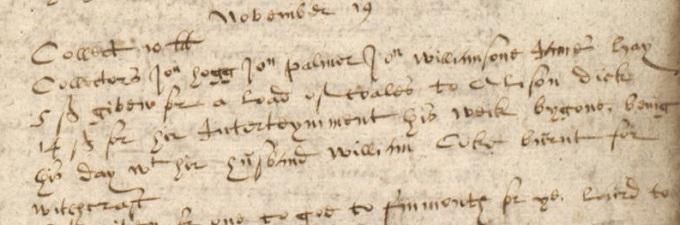

‘November 19

Collect 10 lib[rii]

Collectors Jo[h]n Hogg Jo[h]n Palmer jo[h]n Williamsone James Hay

5 s[olidii]s given for a load of coales to Alison Dick

14 s[olidii]s for hir Interteyniment this weik bygone being

this day w[i]t[h] hir husband William Coke burnt for

Witchcraft.’

Accounts later on in the minutes show that prosecuting witchcraft cases was an expensive and therefore serious undertaking. In the case of Alison and William, they show the costs for paying for the coal, the watch being kept over Alison, purchasing the commission for the trial, arranging for someone to get the laird as judge, as well as payments for tar barrels (so the bodies would burn quickly) and leather straps. The total costs incurred were £16 18s for the kirk session and £17 1s 4d for the burgh.

The cost of prosecuting a witch, Kirkcaldy kirk session minutes, 17th December 1633

National Records of Scotland, CH2/636/34, page 289

‘The towne and sessiouns extraordinar debursments

for W[illia]m Coke and Alison Dick witches

In primis to M[iste]r James Miller when he went to Pres

towne [videlicet] Sept 24 (inserted) for a man to trye them - 47 s[olidii]s

Item to the man of Culrose when he went away

the first tyme - 12 s[olidii]s

Item for coalls for [th]e watches - 24 s[olidii]s

Item in purchaseing [th]e c[om]missioun - 9 lib[rii] 3 s[olidii]s

Item for one to goe to finmouth for [th]e Laird Nov 19 (inserted) - 6 s[olidii]s

Item for harden to be ju[m]ps to them - 3 lib[rii] 10 s[olidii]s

Item for makeing of them - 3 s[olidii]s Summa 16 lib[rii] 18 s[olidii]s

for the kirks part’

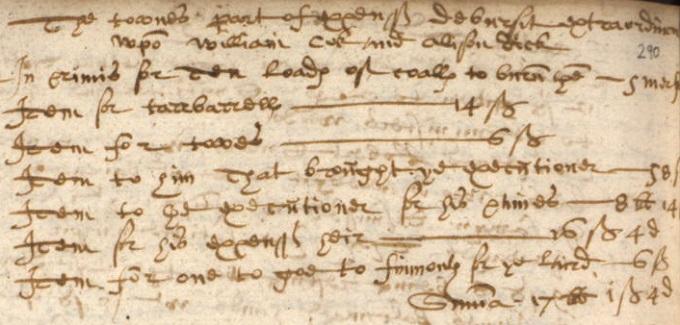

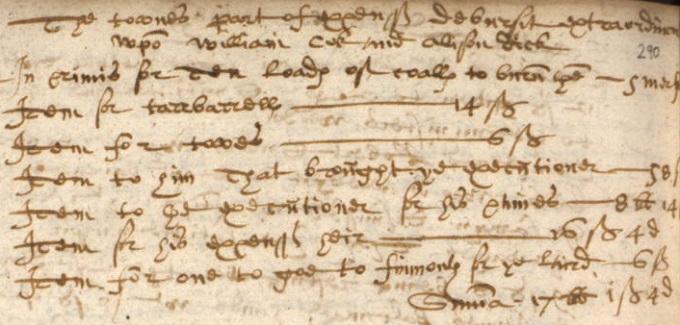

The cost of prosecuting a witch, Kirkcaldy kirk session minutes, 17th December 1633

National Records of Scotland, CH2/636/34, page 290

‘The townes part of expens[is] debursit extraordinar

wpo[n] William Cok and Alison Dick

In primis for Ten loads of coalls to burn the[m] - 5 merks

Item for tarbarrells - 14 s[olidii]s

Item for towes - 6 s[olidii]s

Item to him that brought [th]e executioner - 5 s[olidii]s

Item to the executioner for his paines - 8 lib[rii] 14 s[olidii]s

Item for his expens[is] heir - 16 s[olidii]s 4 d[enarii]

Item for one to goe to finmouth for [th]e Laird - 6 s[olidii]s

Sum[m]a 17 lib[rii] 1 s[olidii]s 4 d[enarii]’

The case of Alison Dick and William Coke shows the key role in which church courts could play in a witch-hunt as well as the process of hearing and dealing with accusations of witchcraft and acting as a pre-trial body. It also demonstrates that with help from the burgh, they could arrange for suspects to be incarcerated and watched, vital for securing a confession. (Macdonald, ‘The Witches of Fife’, pages 150-151).

The decline of witch-hunting

Witch-hunting in Scotland went into a sharp decline following the last ‘panic’ in 1661 to 1662, though levels of prosecution fluctuated throughout the rest of the century with occasional flare-ups.

The decline has been attributed by historians to both a judicial and an ideological scepticism. Gradually over time, although the concept of witchcraft was still a reality for some, the authorities came to believe it was impossible to prosecute cases as a practical matter and were less convinced that the usual kinds of evidence could prove guilt.

The validity of confessions made under torture was questioned, and pricking for the Devil's mark came to be seen as fraudulent. During some of the major panics, particularly in 1661 to 1662, there were miscarriages of justice which led to tightening up of procedures.

After the ‘Glorious’ or ‘Bloodless’ Revolution of 1688-1689, in which James VII and II was overthrown and replaced by his daughter Mary and her Dutch husband William, the state became more secular and no longer needed to prove its godliness by executing witches.

The last person prosecuted before the Lords of Justiciary for witchcraft was Elspeth Rule who was tried before Lord Anstruther at Dumfries Circuit on 3rd May 1709. She was burned on the cheek and banished from Scotland for life.

A small number of local prosecutions continued; the last person executed for witchcraft is said to have been Janet Horne in Sutherland in 1727 but there is no documentary evidence to support this.

The repeal of the Scottish Witchcraft Act

The Scottish Witchcraft Act was repealed in 1736 as a result of a House of Lords amendment to the bill for the post-union Witchcraft Act 1735. The repeal of 1736 abolished the crime of witchcraft and replaced it by a new crime of 'pretended witchcraft' with a maximum penalty of one year's imprisonment.

Portrait of the medium Helen Duncan, undated

Credit: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Helen Duncan, a medium and spiritualist, gained the unlikely notoriety of being the last Scottish person to be imprisoned under the Witchcraft Act of 1735 for fraudulent claims in 1944.

Further reading

For more information, please see the guidance on church court records and Using Virtual Volumes on ScotlandsPeople.

If you are new to reading and interpreting kirk session records, you can find help in our guide to reading older handwriting, the Scottish Handwriting resource and a glossary of abbreviations, words and phrases.

Excerpts from Alison Dick and William Coke’s case are included in John Sinclair, editor, ‘The Statistical Account of Scotland 1791-99’, vol. X, Fife, (Edinburgh, 1978), pp. 807-816.

Julian Goodare, Lauren Martin, Joyce Miller and Louise Yeoman, 'The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft'.

Christine Larner, ‘Enemies of God: The Witch-Hunt in Scotland’, (London, 1981).

B.P. Levack, ‘Witch-Hunting in Scotland: Law, Politics and Religion’, (Abingdon, 2008).

Stuart Macdonald, ‘The Witches of Fife: Witch-hunting in a Scottish Shire’, 1560-1710’.

UK Parliament: An Overview of Witchcraft.