Background information

Special commission of oyer and terminer

The records of the Radical Rising trials

How to search the records of the Radical Rising

What can I learn from the records of the Radical Rising?

Further reading

Background information

The ‘Radical Rising’ or ‘Radical War’ of 1820, also known as the Scottish Insurrection of 1820, was a week of strikes and unrest in Scotland that culminated in the trial of a number of ‘radicals’ for the crime of treason. It was the last armed uprising on Scottish soil, with the intent of establishing a radical republic.

Based in Central Scotland, artisan workers (such as weavers, shoemakers, blacksmiths), initiated a series of strikes and social unrest during the first week of April 1820. This pushed for government reform, in response to the economic depression. The Rising was quickly, and violently, quashed, and the subsequent trials took place in Scotland from July to August 1820.

The events of the Rising followed years of economic recession after the end of the Napoleonic Wars and considerable revolutionary instability on the European continent. As the economic situation worsened for many workers, societies sprung up across the country which espoused radical ideas for fundamental change.

In the early nineteenth century, Scottish politics offered power to very few people. Councillors on the Royal Burghs at this time were not elected to their position, rich landowners controlled county government and there were fewer than 3,000 parliamentary electors in the whole of Scotland.

It was recognised that the key to change was electoral reform, and the events of the American Revolution of 1776 and French Revolution of 1789 helped to promote these ideas. Radical reformers began to seek the universal franchise (for men), annual parliaments, and the repeal of the Act of Union of 1707.

Between 1 and 8 April 1820, across central Scotland, some works stopped, particularly in weaving communities, and radicals attempted to fulfil a call to rise. Several disturbances occurred across the country, perhaps the worst of which was a skirmish at Bonnymuir, Stirlingshire, where a group of about 50 radicals clashed with a patrol of around 30 soldiers.

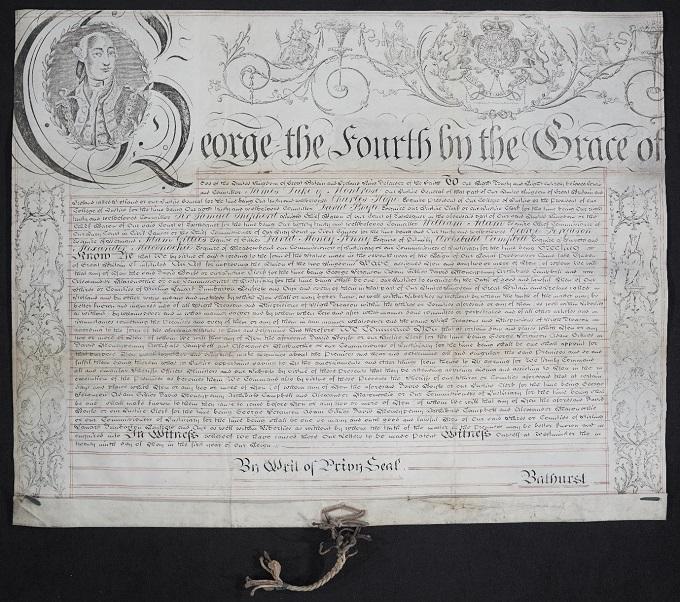

Special commission of oyer and terminer

Special commission of oyer and terminer, 29 May 1820. (Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, JC21/1/1)

On 29 May 1820, a ‘special commission of oyer and terminer’ (translated as ‘to hear and determine’) was granted under the Great Seal of Great Britain. This commission conferred royal authority to hold treason trials in several counties of Scotland for those individuals charged with involvement in what is now known as the Radical Rising.

The ‘special’ commission of oyer and terminer (as distinct from a ‘general’ commission of oyer and terminer) came into common use in England during the reign of King Edward I. A common reason for the establishment of these commissions was an inability to obtain justice at the local level, so the special commission of oyer and terminer carried the law of the Crown from the centre of government to the outlying counties.

Although the Treaty of Union 1707 states “that all Laws in use within the Kingdom of Scotland, do, after the Union and notwithstanding thereof, remain in the same force as before”, the Treason Act of 1708 sought to unify the laws for trials of treason and misprision of treason, effectively bringing English law into the Scottish courts. This was achieved through the use of special commissions of oyer and terminer, where three Lords of Justiciary had to be on the commission.

Bills of treason were issued for 88 men involved in the Radical Rising, detailing the four counts and 19 overt acts of treason with which the men were charged. Only a few of the 88 men were tried, as a significant number had fled the country. Of those tried and found guilty by the special commission of oyer and terminer, 19 were transported to Australia, where they largely found sympathy. The three alleged ring-leaders were executed at Glasgow and Stirling. James Wilson, John Baird and Andrew Hardie came to be seen as martyrs to the cause.

The records of the Radical Rising trials

The highly-significant trial papers of the Radical Rising are held by the National Records of Scotland (NRS). For many years, the papers were thought to have been lost in storage at Parliament House, Edinburgh. In 1972, nineteenth-century records of the High Court of Justiciary were received by the former Scottish Record Office (predecessor of NRS). Because the Radical Rising trials had not taken place under normal Justiciary procedures, the records did not fit into any of the existing High Court record series and were misplaced within the vast High Court collection.

The records were rediscovered among unsorted High Court papers in 1983 by the Keeper of the Records of Scotland though have, until recently, been an under-used resource. The collection has now been fully catalogued, conserved and digitised, and is made fully available online on ScotlandsPeople for the first time. Further details on the process of conserving, cataloguing and digitising the collection are available in two articles on the National Records of Scotland 'Open Book' blog.

Types of record found within the collection include:

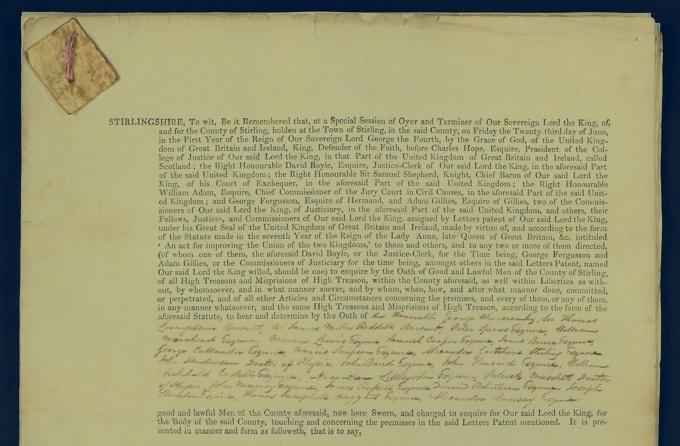

Printed presentments

Trial papers of the Camelon case, Stirling – “a Special Session of Oyer and Terminer […] holden at the Town of Stirling […] on Friday the Twenty-third day of June”, 23 June 1820. (Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, JC21/2/2)

Writ of certiorari

Each special commission of oyer and terminer was essentially constituted as a separate and distinct court. The ‘writ of certiorari’, meant for rare use, is a writ by which an appellate court decides to review a case at its discretion. The word ‘certiorari’ comes from Law Latin and means “to be more fully informed”. A writ of certiorari orders a lower court to deliver its record in a case so that the higher court may review it. In this case, the special commission of oyer and terminer delivered its record to the High Court of Justiciary, and this writ survives as JC21/7.

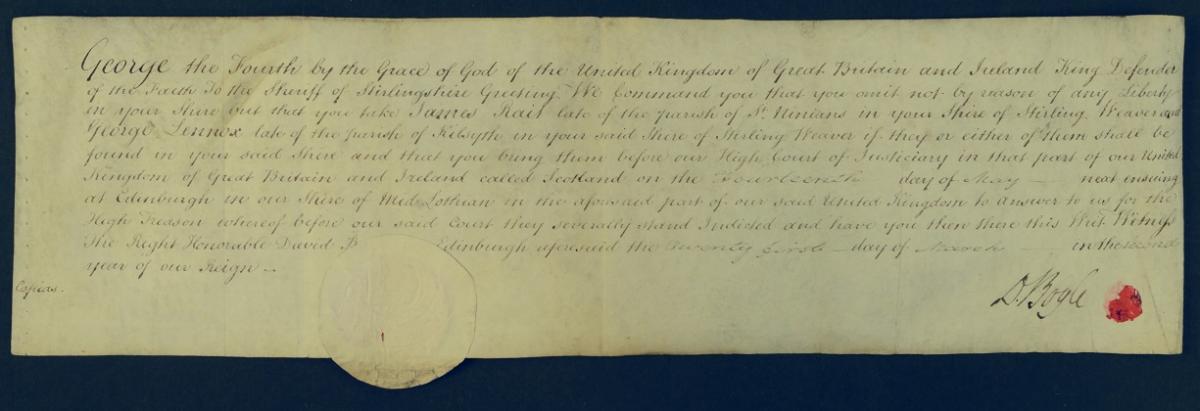

Writs of capias

Writ of capias against James Rait and George Lennox, Stirling, 21 March 1821. (Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, JC21/8/5)

At the termination of the trials in August 1820, several men remained in prison without trial. In a half-hearted attempt to institute new treason trials, ‘writs of capias’ were issued against these men, though all were returned ‘not found’. A writ of capias directs an officer to take into custody the person named in the writ or order. These writs of capias survive in JC21/8.

How to search the records of the Radical Rising

To search for a particular record from the Radical Rising trials, go to the Virtual Volumes search or see our guide on Using Virtual Volumes.

The NRS online catalogue references for the eight series, which can be used for searching the records by reference number in Virtual Volumes, are as follows:

- JC21/1 Commission of oyer and terminer

- JC21/2 Treason Trials: County of Stirling

- JC21/3 Treason Trials: County of Lanark

- JC21/4 Treason Trials: County of Dunbarton

- JC21/5 Treason Trials: County of Renfrew

- JC21/6 Treason Trials: County of Ayr

- JC21/7 Writ of certiorari directing commissioners to certify indictments into High Court of Justiciary

- JC21/8 Writs of capias against persons not brought to trial in 1820

What can I learn from the records of the Radical Rising?

In times of political strife in the United Kingdom, the method of dealing with political rivals was often through the courts. Such cases frequently came before the courts held under commissions of oyer and terminer. As these commissions specialised in cases of treason and armed insurrection, the trial papers of the Radical Rising throw a good deal of light on the politics of the United Kingdom at the time, and of Scotland particularly.

The Radical Rising provides an early example of people understanding the inequality in their society and the importance of electoral representation in order to address it. As such, the surviving trial records are a rich source of political and social history, both at a local and a national level.

Political historians can also use the material to study general aspects of how crimes of treason were dealt with in Scotland in the years after the 1707 Union.

Local historians with a research focus on the counties of Stirling, Lanark, Dunbarton, Renfrew and Ayr will find useful details on important historical events in those localities which are intrinsically linked with the wider social and political landscape in the United Kingdom and Europe at that time.

Further reading

The trial proceedings and evidence were printed verbatim from C. J. Green's shorthand notes in 'Trials for High Treason in Scotland … in the Year 1820', 3 vols (Edinburgh, 1825).

H. W. Meikle, 'Scotland and the French Revolution' (Glasgow, 1912).

P. Berresford Ellis and S. Mac A'Ghobhain, 'The Scottish Insurrection of 1820' (London, 1970). A new edition was published in 2016.

M. Craig, ‘One Week in April: The Scottish Radical Rising of 1820’ (Edinburgh, 2020).

K. MacAskill, ‘Radical Scotland: Uncovering Scotland’s Radical History’ (London, 2020).

Though much of the collection is printed, you may find the legal terminology and occasional handwriting in the trial papers difficult to read and interpret. Look at the guides on reading older handwriting, unfamiliar words and phrases, and search the glossary for assistance with abbreviations, legal terminology, occupations and other unfamiliar words.