Introduction

Per verba de praesenti

Per verba de futuro subsequente copula

Marriage by cohabitation with habit and repute

Why did the Church of Scotland tolerate irregular marriages?

Why did people marry irregularly?

Further reading

Introduction

“The law of Scotland as to marriage was this – it adopted the principle that consent alone made marriage… The law of Scotland did not require the presence of a priest, nor the intervention of any religious ceremony. The law of Scotland considered marriage to be a civil contract, but it did not provide any particular mode by which that contract was to be proved” – Hansard, discussion on bill, Registration of Births and Marriages (Scotland) Bill August 1848.

The recent release of National Records of Scotland’s (NRS) kirk session minutes on Scotland's People, affords the chance to examine these forms of marriage, the impact it could have on people’s lives and how it was recorded by the Church of Scotland.

The laws of marriage were quite different in England and Scotland. In Scotland, marriage was based on the principles of mutual consent and both ‘regular’ and ‘irregular’ marriages were recognised by law. Regular marriages were those performed by the clergy after the publication of banns. There were three forms of irregular marriage in Scotland:

1. Per verba de praesenti – A present exchange of consent by words by both parties to be married, privately or informally given, to be man and wife. Ideally this exchange would be performed in front of witnesses; a marriage contract without was still legal but much more difficult to prove.

2. Per verba de futuro subsequente copula – A promise of future marriage without a present exchange of consent, ‘followed at a subsequent time by carnal intercourse’.

3. Marriage by cohabitation with habit and repute. Generally this meant a couple living together and publicly behaving as though they are man and wife. This could include being affectionate, and referring to each other as ‘husband’ and ‘wife’. Also known as a ‘common law’ marriage, this was not so much a form of marriage, but a separate type of evidence which could be used to establish that a marriage had taken place. If a couple had lived and presented themselves as married for an extended period of time, there was a presumption that there had been a previous exchange of consent.

Irregular marriages remained valid until 1939 because the Scots held to the simple doctrine that any two unmarried people of lawful age (until 1929 12 for a girl, 14 for a boy) that wished to get married, if they were physically capable and not within the prohibited degrees of kinship, ‘and they both freely expressed this wish and freely accepted each other in marriage, then they were married’ (T. C. Smout). Consent made the marriage, not the clergy nor the civil official, and there were no restrictions on where and when the marriage might take place, nor a requirement that witnesses be present to prove its validity.

By contrast, in England the law of marriage has been determined by the Clandestine Marriages Act 1753, more generally known as Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act. This was modified by the Act for Marriages in England 1836, or ‘Lord Russell’s Act’. This made all marriages equally regular, but they could be in either the religious or civil mode. The former would take place in church before a clergyman after the publication of banns or after obtaining an ecclesiastical licence, while the latter took place before a registrar after a posted notice of the marriage.

Per verba de praesenti

In Scotland an irregular marriage, if it could be proved, had all the same legal consequences of a regular one. Mainly that a man had an enforceable claim on the woman’s property, and the women and children of the marriage, upon her husband’s death, had a claim to his estate.

Throughout the kirk session minutes there are numerous examples, in almost every parish of irregular marriage, the sin of fornication, and also ‘ante-nuptial fornication’; in other words, having sex with your now husband/wife before the marriage had taken place. How these acts of intimacy were discovered varied, from witnesses coming forward, perpetrators confessing, or in some cases because of the impressive investigative skills of the church session.

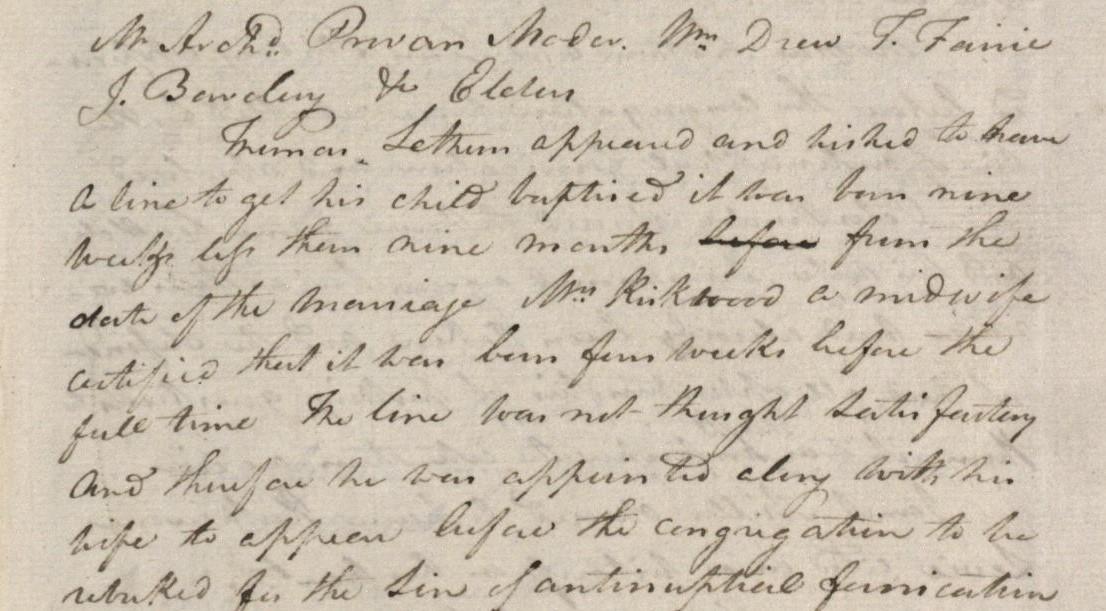

The case of Thomas Lethum in 1801 who approached the session requesting ‘a line to get his child baptised’ is one such example. The Cadder kirk session record that the child was,

“…born nine weeks less than nine months from the date of the marriage. Mrs Kirkwood a midwife certified that it was born four weeks before the full time. The line was not thought satisfactory and therefore he was appointed along with his wife to appear before the congregation to be rebuked for the sin of antinuptial fornication”

Cadder kirk session minutes, 3rd May 1801

National Records of Scotland (NRS), Cadder kirk session minutes,CH2/863/3 page 71

In the minutes of the Cadder kirk session between 1798 and 1882 (NRS,CH2/863/3) there are repeated entries referring to couples appearing before the session acknowledging themselves to be husband and wife, and being ‘rebuked for their irregularity and absolved’ and fined.

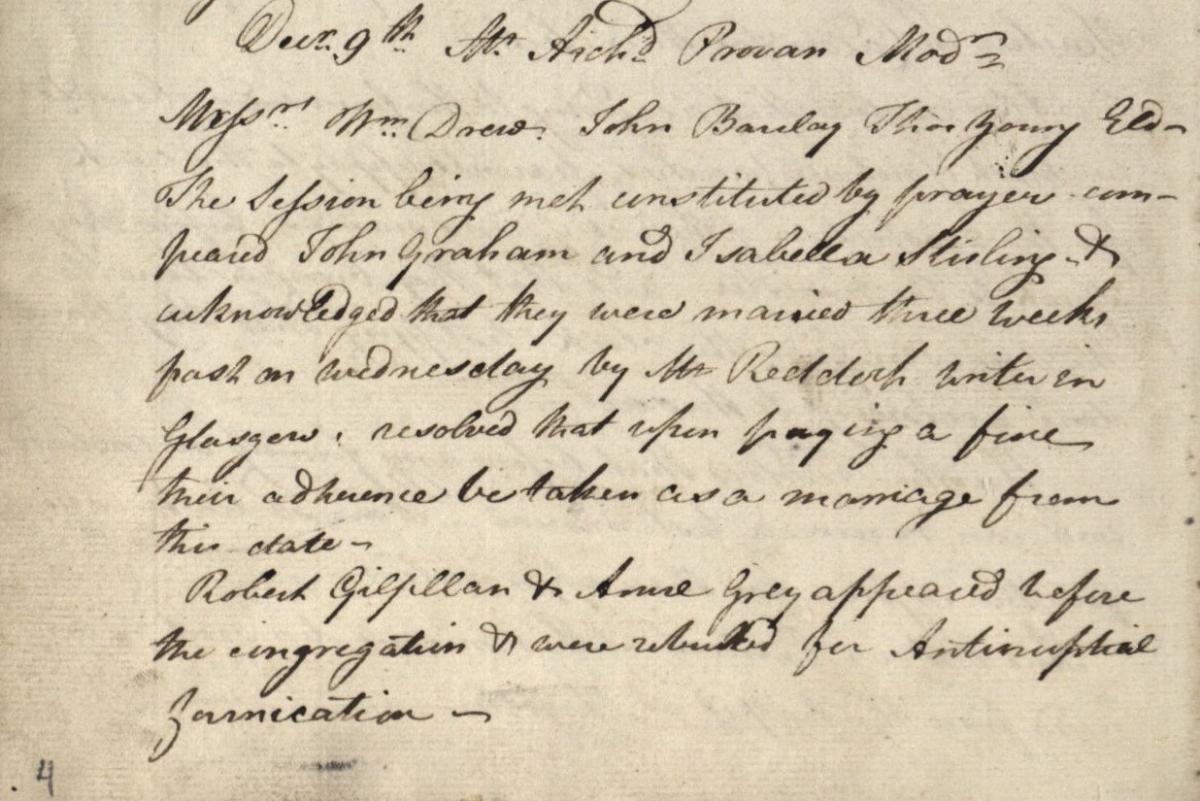

Cadder kirk session minutes, 9th December 1798

NRS, Cadder kirk session minutes,CH2/863/3 page 4

“The session being met constituted by prayer compeared John Graham and Isabelle Stirling acknowledged that they were married two weeks past on Wednesday by Mr Reddoch writer in Glasgow, resolved that upon paying a fine their adherence to be taken as a marriage from this date”

Cadder kirk session minutes, 26th June 1800

NRS, Cadder kirk session minutes,CH2/863/3 page 42

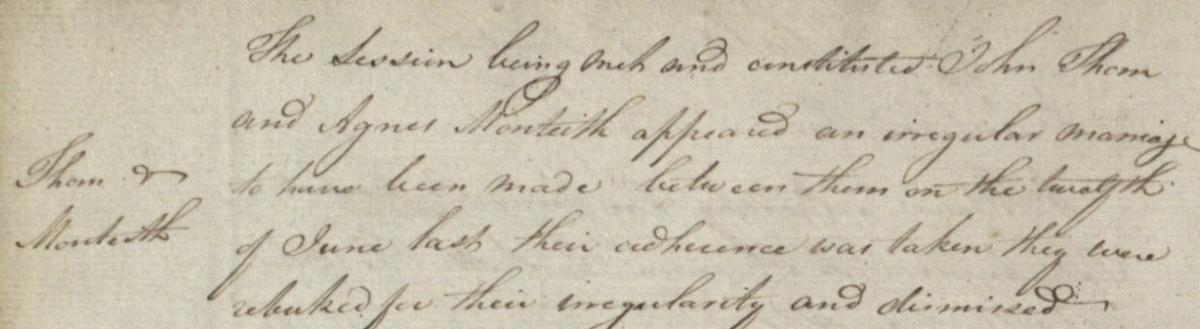

“The session being met and constituted John Thom[son] and Agnes Monteith appeared an irregular marriage to have been made between them on the twelyth of June last their adherence was taken they were rebuked for their irregularity and dismissed”. 26th June 1800

When both parties confessed the marriage, while they still might be required to provide proof, there were less likely to be issues beyond a public rebuke and a fine. Problems occurred when one party claimed a marriage, and the other denied it.

Per verba de futuro subsequente copula

From May 1799 till the beginning of 1800 a case appears in the Cadder kirk session minutes concerning a claim of promised marriage.

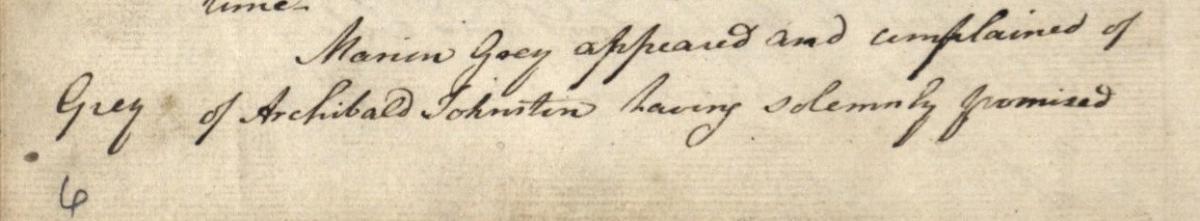

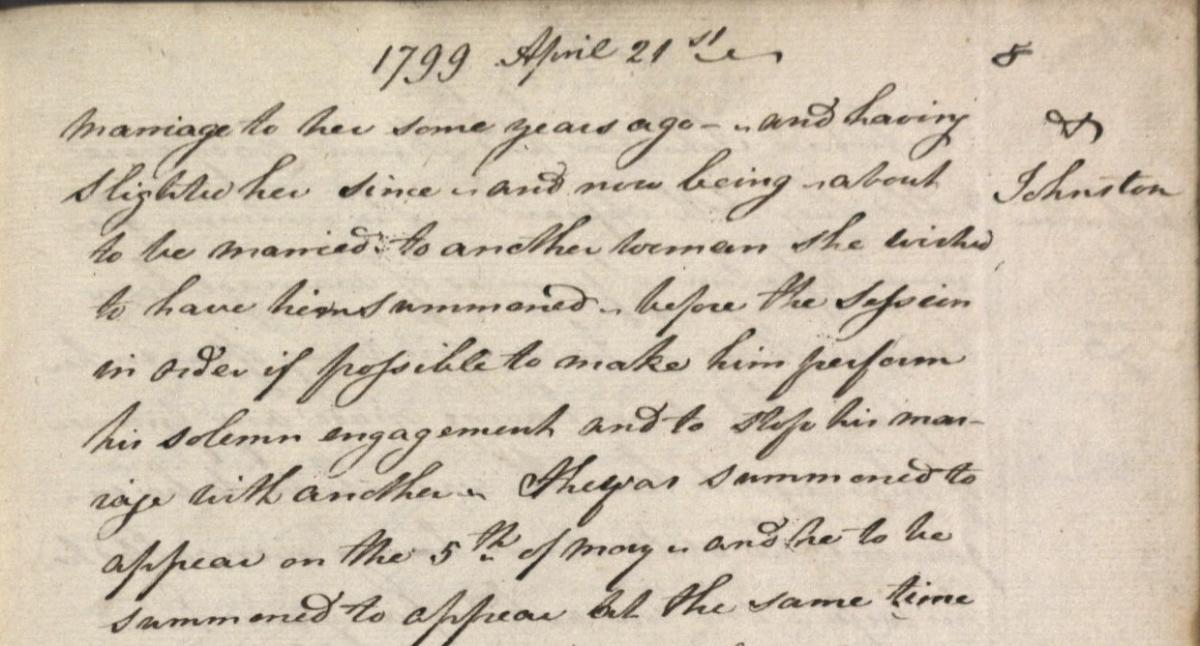

“Marion Grey appeared and complained of Archibald Johnston having solemnly promised marriage to her some years ago and having slighted her since is and now being about to be married to another woman she wished to have him summoned before the session in order if possible to make him perform his solemn engagement and to stop his marriage with another. He is summoned to appear on the 5th of May and her to be summoned to appear at the same time”.

Cadder kirk session minutes, 21st April 1799

NRS, Cadder kirk session minutes, CH2/863/3 pages 6 and 7

Archibald Johnston denied this promise stating to the session that ‘he confessed being often in her company but denied having made any promise of marriage to her’. In this situation the session sought evidence to prove that Johnston had intended marriage and asked Grey whether there were any witnesses to him calling her ‘wife’ or to establish if the couple treated each other as husband and wife. Evidence could include witnesses to affectionate behaviour and either person acknowledging the other as ‘husband/wife’ in public, as well as the submission of letters that were addressed to each other in a similar manner.

Several witnesses were called before the session between 5th May and 8th September 1799. They all claimed ignorance; the session considered it impossible to pursue the claim any further without more evidence and the case was dismissed on 8th August 1799. Despite this, Marion Grey appears again on the 25th and states that she could provide proof of her being ‘bedded’ with Archibald Johnston and further witnesses were called.

After several meetings with individuals that knew nothing of the matter, on the 26th September 1799 Marion Grey called Mr Craig and Helen Drummond as witnesses who provide the following account of their stay at a public house:

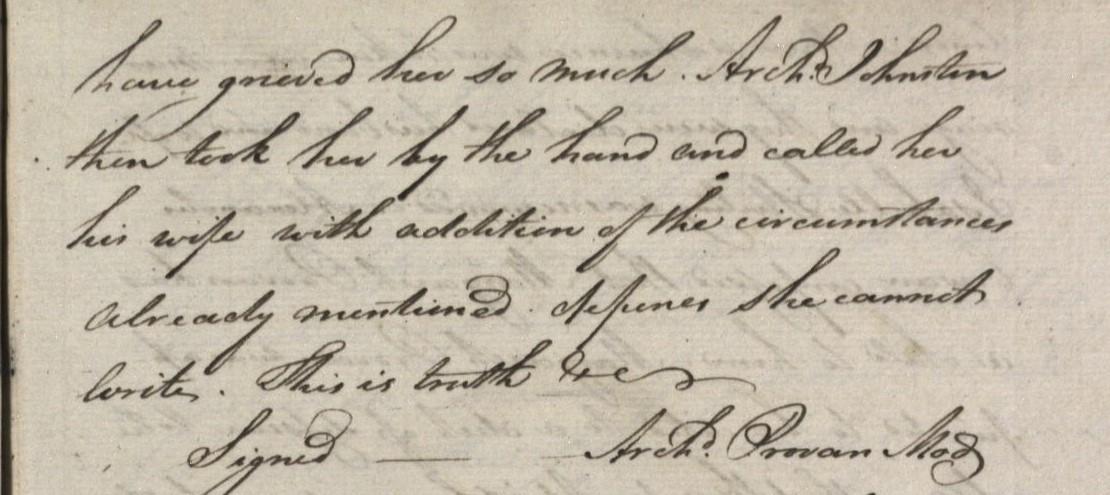

“‘through a skreen which divided the apartments she saw Archibald Johnston and Marion Grey together and they then she heard [Archibald] Johnston call Miss Grey his wife and assure her that he would provide a house for them to stay together when he had settled his mother. The deponent adds that [Archibald] Johnston said that he could not get lines to day but that he thought there was enough between them without lines. Marion Grey appears to be anxious on this account upon which [Archibald] Johnston asked her why she was so grieved. Marion Grey said that if nothing had been between them nothing else could have grieved her so much. [Archibald] Johnston took her by the hand and called her his wife with addition of the circumstances already mentioned”.

Cadder kirk session minutes, 26th September 1799

NRS, Cadder kirk session minutes, CH2/863/3 pages 22 and 23

A Mr Harrion and Katharine Rankine also state that they heard Johnston call Grey his wife at the same public house.

The session concludes that they are not the competent court to declare whether Archibald Johnston and Marion Grey are husband and wife, but neither can they allow the proclamation of banns for Johnston’s ‘new’ marriage to proceed until the case had been ruled on by a competent court. They refer the matter to the presbytery who, on the 8th December 1799 return an interesting conclusion:

“Mr Provan reported from the presbytery with regard to the affair of Arch[ibald] Johnston and Marion Grey. That the session ought not to have taken the affair into their cognisance till Arch[ibald] Johnston had applied for proclamations but that after the affair was taken in their sentence ought to have been this. That a definite time, a month or six weeks, should have been appointed after which Arch[ibald] Johnston should be at liberty to have proclamation of banns. Still leaving in the power of Marion Grey to stop the proclamation by a Dis[missal] from an adequate civil court. The former sentence of session therefore annulled and after six weeks from the date of meeting of last prysbtery Arch[ibald] Johnston is considered as being at liberty to have proclamation in order to marriage” (NRS,CH2/863/3 page 32).

At this point, the story of Marion Grey and Archibald Johnston disappears, but is clearly not yet resolved.

Marriage by cohabitation with habit and repute

Due to the close nature of communities and the church, it was very rare for a claim of marriage by ‘habit and repute’ to be raised as it would be very difficult for a couple to cohabit for any length of time without the local session enquiring as to their marital status.

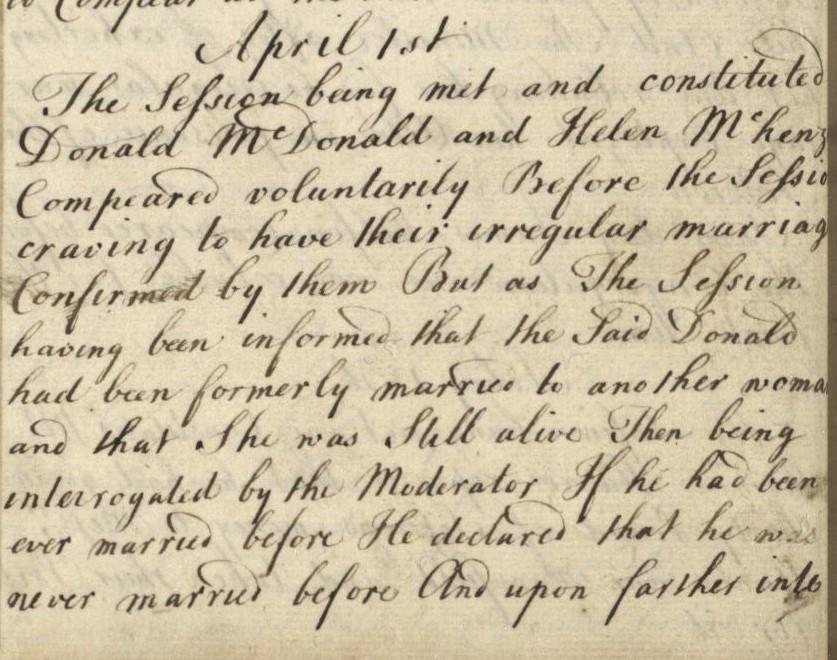

One such incidence does appear in the Dalkeith kirk session in April 1770. Donald McDonald and Helen McKenzie appear before the session voluntarily to have their irregular marriage confirmed. However, the session has been informed that McDonald has been previously married to another woman. Upon interrogation:

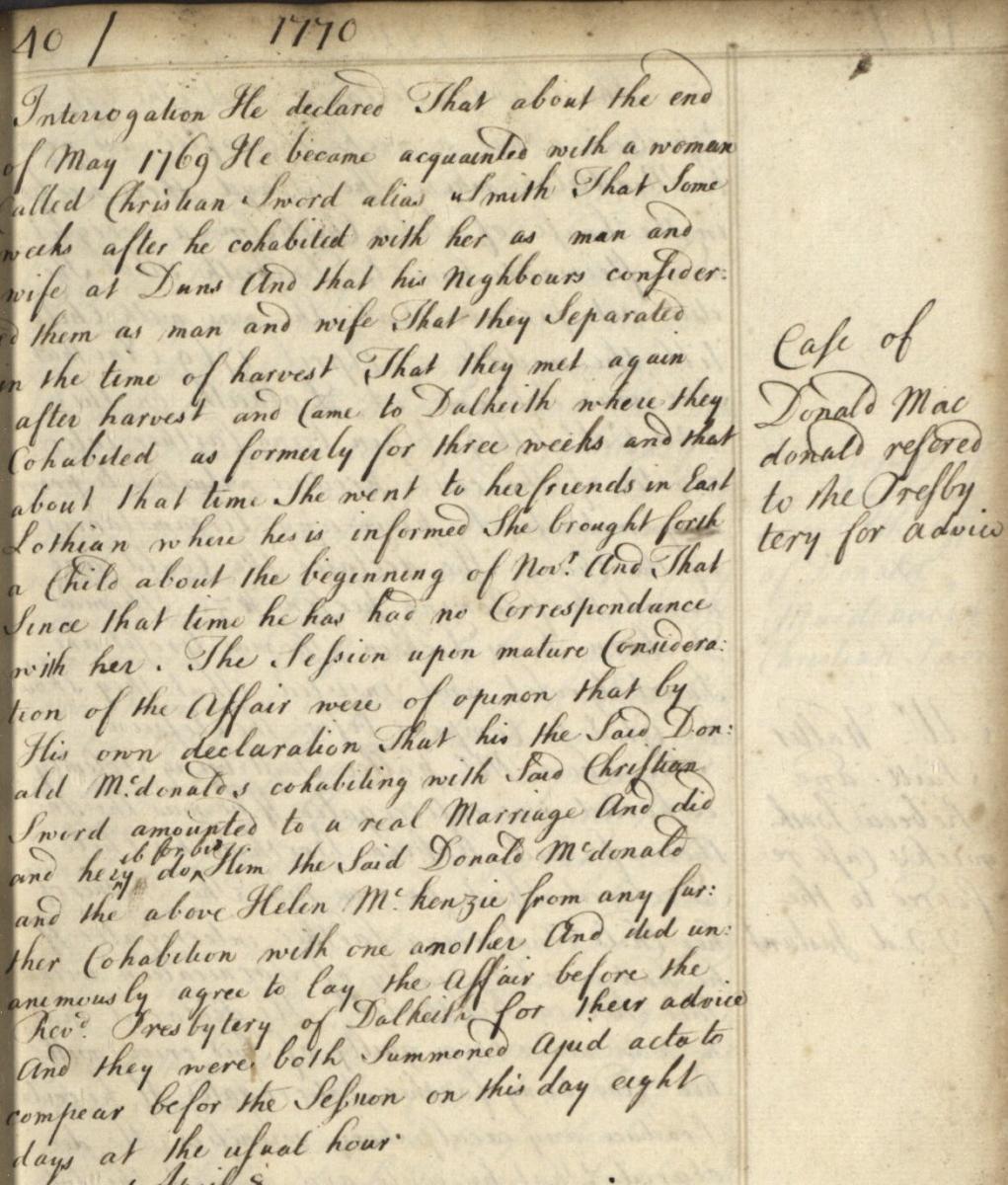

“He declared that he was never married before and upon farther interrogation he declared that about the end of May 1769 he became acquainted with a woman called Christian Sword alias Smith that some weeks after he cohabited with her as man and wife at Duns and that his neighbours considered them as man and wife That they separated in the time of harvest That they met again after harvest and came to Dalkeith where they cohabited as formerly for three weeks and that about that time she went to her friends in East Lothian where he is informed she brought forth a child about the beginning of Nov[ember] and that since that time he has had no correspondence with her. The session upon mature consideration of the affair were of opinion that by his own declaration that his the said Donald McDonald cohabiting with said Christian Sword amounted to a real marriage” (NRS,CH2/84/13 page 40).

Dalkeith kirk session minutes, 1st April 1770

NRS, Dalkeith kirk session minutes,CH2/84/13, pages 39 and 40

In this instance, the session come to the conclusion that McDonald’s time with Sword constituted a ‘real marriage’.

This is an unusual example. In most cases a marriage by ‘habit and repute’ would be put before the session by women wishing to secure their situation, and that of their children, in the eyes of the law and to ensure that their children were baptised. This could be particularly relevant to the partners of soldiers, where their husband’s potential death and lack of a recorded marriage, could put the family at risk.

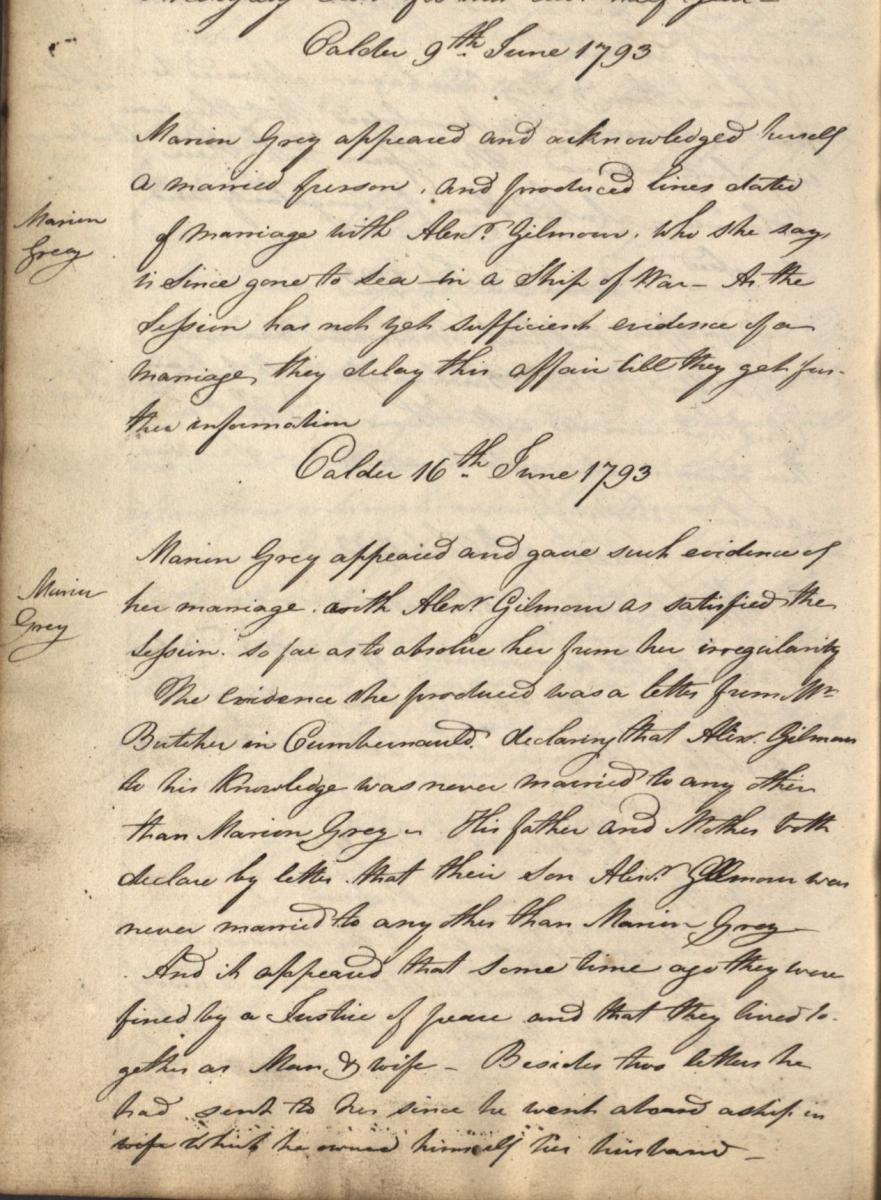

For instance, in the case of another Marion Grey, she approaches the Cadder kirk session to have her irregular marriage to Alexander Gilmour recognised. Gilmour has since gone to ‘sea in a ship of war’, and once adequate proof is provided – in this case correspondence from Gilmour, witnesses to their married life and a fine paid to the Justice of Peace – their marriage appears to be accepted.

Cadder kirk session minutes, 9th and 16th June 1793

NRS, Cadder kirk session minutes,CH2/863/2 page 236

“Marion Grey appeared and acknowledged herself a married person, and produced lines dated of marriage with Alex[ander] Gilmour, who she says is since gone to sea in a ship of war. As the Session has not yet sufficient evidence of a marriage they delay this affair till they get further information".

The Cadder kirk session minutes continues with Marion Grey's case on the 16th June 1793:

“Marion Grey appeared and gave such evidence of her marriage with Alex[ander] Gilmour as satisfied the Session so far as to absolve her from her irregularity.

The evidence she produced was a letter from Mr Butchers in Cumbernauld declaring that Alex[ander] Gilmour to his knowledge was never married to any other than Marion Grey. His father and mother both declare by letter that their son Alex[ander] Gilmour was never married to any other than Marion Grey.

And it appeared that some time ago they were fined by a Justice of Peace and that they lived together as man & wife. Besides there letters he had sent to her since he went aboard a ship in which he owned himself her husband” (National Records of Scotland,CH2/863/2 page 236).

Why did the Church of Scotland tolerate irregular marriages?

The acceptance of the Church of Scotland of irregular marriage in many ways seems extraordinary given the problems it could cause. It was impractical to distinguish between a present vow and future promise; it allowed couples to marry outside of the control of their parents, a particular worry for the propertied classes where the economic and political considerations of a match could be disregarded; and it undermined the attempts of the church to regulate marriage. So why allow it to continue?

At the Council of Trent in 1563 the Roman Catholic Church barred all forms of marriage other than that constituted by a public ceremony. The reformers in Scotland had a choice between following this line or adhering to the old forms of marriage. As the change proposed by the Roman Catholic Church put marriage in the hands of the clergy, the militant lay kirk sessions of Scotland resisted it and chose to retain the other traditional forms of marriage, although it would come to stress that the proclamation of banns followed by a ceremony in church was a ‘true marriage’.

So why did the kirk sessions spend so much time endeavouring to establish bona fide irregular marriages? In Scotland, the original Protestant confession of 1560 declared that a godly discipline was one of the signs of the true church. This ‘true church’ was a body of the elect and the National Confession of Faith defined it as a ‘company and multitude of men chosen by God’, so a congregation could not consider itself part of this company unless it sustained discipline. The system of regular discipline enforced by the church courts and recorded in the kirk session minutes was therefore an essential part of the affirmation by the community of its membership of the elect. While the recording and punishment of sins such as ‘anti-nuptial fornication’ seem spectacularly invasive today, and in many ways redundant as a marriage had taken place, it was believed necessary because without enforcing Christian discipline, the very salvation of the community might be in doubt. This fear extended not only to individual retribution by God, but that a sinful society would be punished as a whole, with events such as famines and plagues viewed as a divine punishment.

Another reason might be to assert the church’s authority. By insisting that irregularly married couples appear before the session, they asserted a measure of control over the population. Similarly there were economic reasons for establishing a marriage; if a family came to rely on poor relief through sickness, and it could be proved that they were married, the man’s parish were responsible for the women and children – if not, then the woman’s parish would be. Without a record of local marriages, managing poor funds could be difficult.

However, a more generous interpretation might be that the church had a genuine desire to protect innocent victims. There was no ambiguity around a couple that had been publicly proclaimed and married, but irregular marriages were not so straightforward.

Why did people marry irregularly?

So why did people participate in irregular marriages, particularly women, where the difference between a legally binding marriage and an illicit affair could profoundly alter their, and their children’s, status and situation?

Marriage service at the blacksmith's workshop in Gretna Green.

Credit: Public domain, Wikimedia Commons

The ability to marry quickly with minimal questions asked was likely a big attraction for parties in a hurry, or wishing to avoid the scrutiny or knowledge of their plans that public banns might bring about. This could be for a number of reasons; for some, it might have been an attempt to get away with bigamy. Irregular marriages by their nature, were not necessarily recorded, and perpetrators could potentially maintain several relationships – and escape them - without getting caught. For others, parental opposition might be a factor. The difference in marriage law between Scotland and England was well known, this led to couples crossing the border to marry at places like Gretna Green, Coldstream and Lamberton Toll. Those that visited could procure the services of the local blacksmith or person to act as a witness and be married with minimal fuss and intervention.

Another motive might be differences in religious practice. For those who wanted to marry someone from the Church of England, or who was Roman Catholic, they would not necessarily be allowed to marry in the Church of Scotland. To enter into a union they might be forced to marry clandestinely, or over the border in the Church of England, and later be recorded by the session as ‘irregular’.

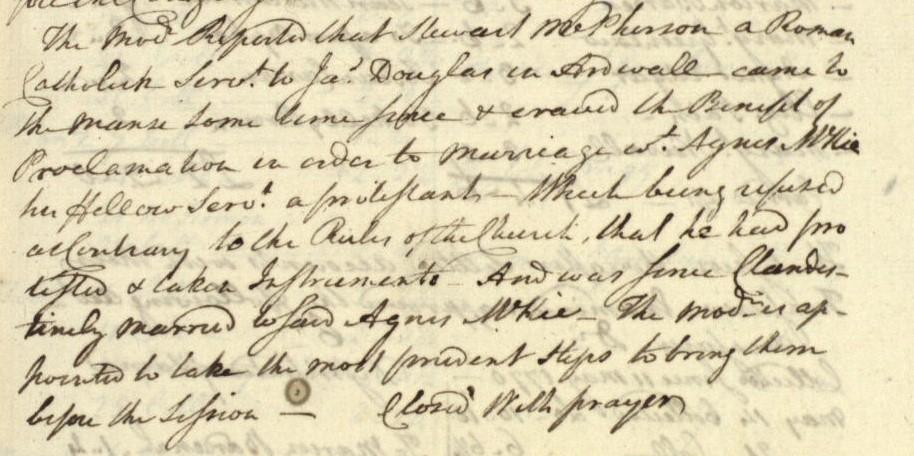

One such example in the kirk session minutes of New Abbey in 1770, records Stewart McPherson, a Roman Catholic, asking the session to be proclaimed for marriage with Agnes McKie, a Protestant. When the minister refused, they left and married irregularly. Despite refusing to marry them, the irregular marriage was later accepted.

New Abbey kirk session minutes, 27th January 1770

NRS, New Abbey kirk session minutes,CH2/1042/3 page 13

“The mod[erator] reported that Stewart McPherson a Roman Catholic serv[ant] to Ja[mes] Douglas in Ardwall came to the manse some time since & craved the Benefit of proclamation in order to marriage w[i]t[h] Agnes McKie his Fellow serv[an]t a protestant which being refused as contrary to the rules of the church, that he had protested & taken instruments. And was since clandestinely married to said Agnes McKie. The moder[ator] appointed to take the most prudent steps to bring them before the session.”

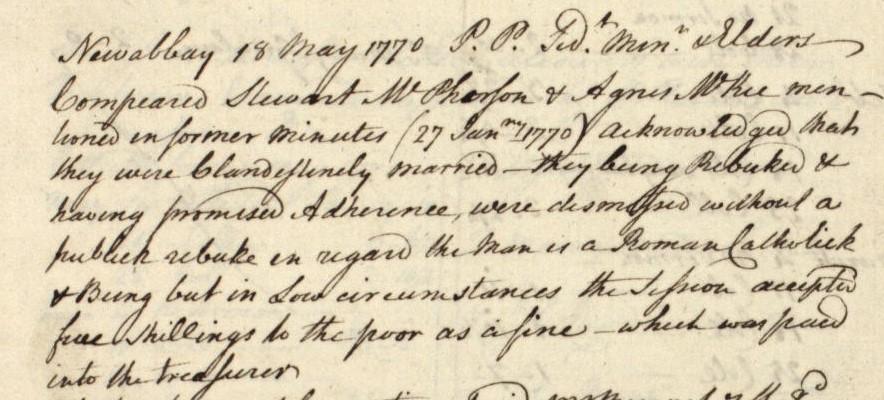

New Abbey kirk session minutes, 18th May 1770

NRS, New Abbey kirk session minutes,CH2/1042/3 page 16

“Compeared Stewart McPherson & Agnes McKie mentioned in former minutes (17 Jan[uary] 1770) acknowledged that they were clandestinely married – they being rebuked & having promised adherence, were dismissed without a publick rebuke in regard the main is a Roman Catholick & being but in low circumstances the session accepted five shillings to the poor as a fine – which was paid into the treasurer”.

While it is not possible to conclude why irregular marriages happened with 100 per cent accuracy, outside of some criminal intentions, it appears to have been a combination of convenience, independence, and necessity.

Further reading

For more information, please see the guidance on church court records and Using Virtual Volumes on Scotland's People.

If you are new to reading and interpreting kirk session records, you can find help in our guide to reading older handwriting, the Scottish Handwriting resource and a glossary of abbreviations, words and phrases.

Resources used:

T.C. Smout, A History of the Scottish people 1560-1830, 1970

Rosalind Mitchison & Leah Leneman, Girls in Trouble: sexuality & control in rural Scotland 1660-1780, 1998

Leah Leneman, Promises, Promises: Marriage Litigation in Scotland 1698-1830, 2003

Leah Leneman, Marriage as interpreted by church and state in eighteenth-century Scotland, Marriage as interpreted by church and state in eighteenth-century Scotland (euppublishing.com)

University of Glasgow, The Scottish Way of Birth and Death, Marriage, University of Glasgow - Schools - School of Social & Political Sciences - Research - Research in Economic & Social History - Research projects - Scottish Way of Birth and Death - Marriage