For the first time we have made General Assembly records available online. This is the governing body and highest court of the Church of Scotland. The records of the General Assembly often reflect pivotal moments in Scotland’s history and give insight into the workings of the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

These are part of the recent release of church court records on Scotland's People which has widened the breadth of the types of church records now accessible on the site. Within the kirk session volumes are a wealth of newly added categories of records which are useful sources for church, family and social historians.

The General Assembly is overseen by an appointed Moderator and ministers and elders are commissioned to attend and given the power to vote on Church law. We have studied the Acts of the General Assembly and found the turbulent meeting in 1638 which documents an significant episode in Scotland’s history.

The opening page of 'A briefe collection of the passages of General Assembly holden at Glasgow', 1638.

National Records of Scotland (NRS), CH1/1/6 page 2

The meeting and outcome of the General Assembly of 1638 had a formidable impact not just on the Church of Scotland and its worshippers but also on the relationship between Scotland and England. In fact, certain historians have said the acts passed by the 1638 Assembly resulted in war.

James VI and I had introduced a hybrid hierarchy of the governance of the Church of Scotland between Episcopacy and Presbyterianism. The General Assembly was the highest court with a temporary moderator directing meetings and Jesus Christ was regarded as the head of the church. The Episcopal (or Anglican) churches adhere to a hierarchy governed by bishops which was introduced by James, and eager to control the General Assembly's discussions. The initiation of the ‘Five Articles of Perth’ forced Episcopal and Roman Catholic methods of worship into the Scottish Church. These included confirmation by bishops, observance of certain holy days and kneeling for communion. Again, these practices were resisted by Scottish ministers, but those who opposed them were removed from their position and even imprisoned.

Charles I sought to further his father’s religious ambitions. Charles was an unpopular figure in Scotland. He had not visited Scotland since his Scottish coronation in 1633 (at which he insisted was conducted using the Anglican rite) and had made some unwelcome changes to the way Scotland was governed by the Privy Council. This comprised an increased number of bishops being appointed to the Privy Council and the Bishop of St Andrews (at the time John Spottiswoode) becoming Lord Chancellor of Scotland. These changes were unpopular with the Presbyterians, who wanted the state and the church to be separate entities. They also disliked the increasing power bestowed on a growing number of bishops, and they used the situation to incite suspicion and discontentment within their followers.

Dissent and the National Covenant

The introduction by Charles I of a new prayer book which was to be used ‘throughout the Realme of Scotland’ to conduct worship prompted a sequence of disorderly events. The prayer book was a thinly disguised version of the English Book of Common Prayer and had been produced without the input of the General Assembly or the Scottish Parliament. On Sunday 23 July 1637 the congregation of St Giles, Edinburgh rebelled and the minister was attacked as he began his sermon. The widely circulated but apocryphal story of Jennet (or Jenny) Geddes, a market trader, was one such alleged rebel. Geddes, supposedly outraged by the use of the prayer book, flung a stool at the Dean. The incident turned into a full-scale riot which brought out the town guard.

Illustration of Jennet Geddes throwing the stool at Minister Hannay. From 'Witnesses for the Truth in the Church of Scotland' by W.P. Kennedy, 1843.

Public domain, taken from www.archive.org

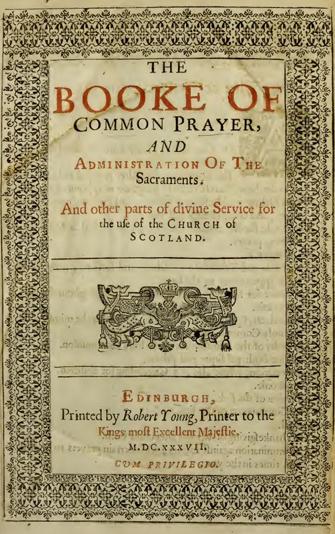

A page from ‘The booke of common prayer, and administration of the sacraments: and other parts of divine service for the use of the Church of Scotland’, 1637.

Image credit: Public domain, www.archive.org

These events along with the growing dissent of the Scottish people led to the drawing up of the National Covenant, which rejected Charles’ reforms or ‘innovations’ as they were phrased in the Covenant and emphasised that all signatories were loyal to the king to prevent charges of treason.

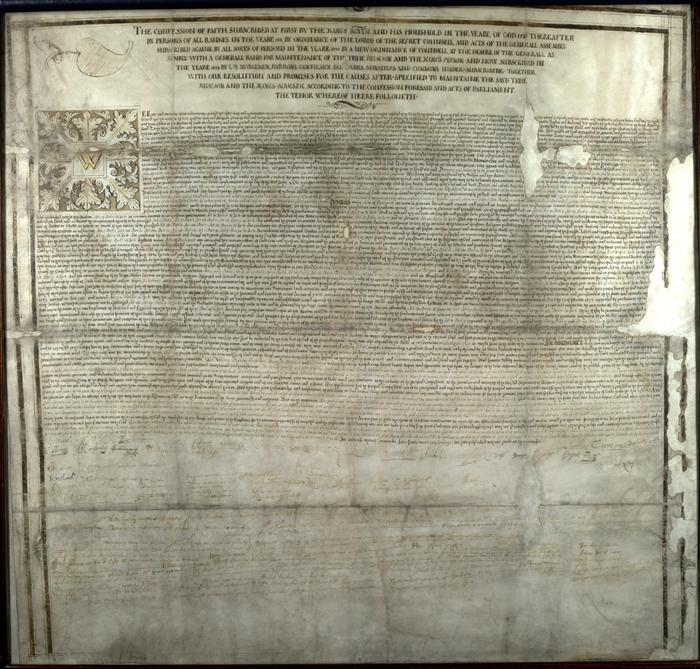

National Covenant which was signed in protest against Charles I’s religious reforms in Scotland. Copies were sent to every corner of Scotland.

NRS, GD40/12/2. Accessible on Scotland's People image library.

The General Assembly of 1638

It was 20 years since the Assembly had last sat in 1618. During that time, James VI and I and his son Charles I had attempted to influence the Church of Scotland to reflect the customs of the Church of England. The General Assembly of 1638 undid all that the two kings had put in place. Gathering in Glasgow on 21 November that year, the city was probably chosen because it was less hostile location, and far enough from the site of rebellion in Edinburgh. Despite these efforts, Glasgow Cathedral was crowded with members of the public and the commissioners ignored the noise to continue their business. The king’s representative, the Duke of Hamilton, withdrew on 29 November, along with a handful of ministers and elders. A large number of members sat on and passed a series of acts over the next two weeks that shaped the Church’s future:

- The Five Articles of Perth were rebuked

- The position of bishop was abolished and all bishops threatened with excommunication

- All imposed Anglican methods of worship, including the Scottish Prayer book, were revoked and condemned

- Members of clergy were barred from holding positions in civic office

- It was initiated that the General Assembly would meet annually

- Image

The Act deposing John Spottiswood (and others) from his ‘pretended’ position of Bishop of St Andrews at the General Assembly of 1638.

NRS, CH1/9/1 page 15

The measures to eradicate Anglican observances in the Church of Scotland led to fifty years of unrest, including ultimately civil war. Charles I instructed troops to march to the Scottish border in what was to become known as the first Bishop’s War. The second Bishops’ War and the Scots’ successful seizure of Northumberland eventually led to Charles calling the Long Parliament in November, 1640, hastening the English Civil War. The Church of Scotland was established as Presbyterian in an Act of Parliament in 1690.

The closing passage from the Register of General Assembly at Glasgow, 1638. It reads:

And so after prayer by the moderator, singing of the

23 Psalm, and the blessing, The assembly de-

parted joyfull and glad in heart, for all

the wonders that God had wrought

for this church and

Land

Finis

NRS, CH1/1/4 page 278

The handwritten registers and printed acts of the General Assembly 1560 – 1900 are available to view on Scotland's People using the Virtual Volume search.

Further reading

Thomas Pitcairn, Acts of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland 1638-1842

Chris Langley, ‘Decorum, emotion and moderation at the Glasgow Assembly, 1638’, Historical Research, 93 (2020)

For more information on these records please see the guidance on our Church Court records and using Virtual Volumes on Scotland's People.

If you are new to reading and interpreting church court records, you can find help in our guide to reading older handwriting, the Scottish Handwriting resource and a glossary of abbreviations, words and phrases.