Introduction

Using church court records

Presbyterian church organisation and records

Parishes (kirk sessions)

Secession church congregations

Presbyteries

Synods

General Assembly

Presbyterian churches in Scotland

Introduction

Presbyterian churches in Scotland are organised into a hierarchy of church courts: kirk sessions, presbyteries, synods and the General Assembly. The records of these courts comprise a major source of information for researching many aspects of Scottish history from 1560 onwards.

In partnership with several local authority and university archives in Scotland, National Records of Scotland (NRS) look after the records of the Church of Scotland and several other Presbyterian denominations.

Using church court records

Church court records are used by a wide variety of researchers. Social historians use them to study everyday life in Scotland from the sixteenth century onwards, since the records contain information about the church’s control of economic activity, moral and sexual behaviour. Kirk sessions also had important functions in school education and poor relief.

Church historians use church court records to study general aspects of religion in Scotland and the history of specific parishes and church buildings.

For family historians, kirk session and presbytery records are often the first step away from sources (such as registers of birth and census returns) which are not indexed intensively by personal name. They can give details of births, marriages, burials and the movement of people from one part of Scotland to another. Evidence given in kirk session and presbytery cases can give fascinating details of how our ancestors lived, worked and worshipped.

To search for a particular kirk session, presbytery, synod or the General Assembly, go to the Virtual Volumes search or see our guide on using Virtual Volumes.

Presbyterian church organisation and records

At the base of the Church of Scotland were its parishes, grouped into presbyteries. The presbyteries in turn were gathered into synods and all these bodies were answerable to the General Assembly at the apex of the Church. The Assembly usually met annually in Edinburgh yearly and when not sitting was represented by a Commission. The summaries of organisation and records given here relate primarily to the Church of Scotland. In practice, when congregations seceded from the Church of Scotland they set up their own kirk sessions, presbyteries, general assemblies, and (in some cases) synods. These bodies all had similar functions to those of the church they had left behind and they created similar records.

Parishes (kirk sessions)

Parishes were originally a way of dividing up the country into small areas, each of which would support a local church and associated clergy. In the eighteenth century there were about 940 parishes. Over the years, there have been countless boundary changes, amalgamations, changes of name and abolitions of parishes. Each congregation (or parish) of the Church of Scotland has a kirk session, which comprises the minister(s) and the ruling elders. The elders’ duty is care for the spiritual needs of the congregation, with a district of the parish assigned to each. The minister is moderator of the session, and a clerk has custody of all the session's records. There may also be a treasurer, and an officer or beadle. The session's duties are to maintain good order amongst its congregation (including administering discipline and superintending the moral and religious condition of the parish), and to implement the Acts of the General Assembly.

The main types of record created by kirk sessions are listed on the kirk session records guide.

Parishes quoad omnia

A quoad omnia parish was a parish for civil and religious purposes. It had a kirk session and heritors. After 1845 it would have had a parochial board for poor relief and public health, which was partly elected and still contained unelected representatives from Church of Scotland kirk session and heritors. In 1892 parochial boards were replaced by wholly elected parish councils.

Parishes quoad sacra

A quoad sacra parish (from the Latin: 'for sacred purposes') had a kirk session but did not have heritors. In the nineteenth century, many large parishes were sub-divided into two or more parishes quoad sacra. Often this was where the parish contained two separate large villages or towns, for example where an industrial town had either grown up some miles from the old parish church or where it arose on the boundary between two parishes. If a parish was divided into two or more quoad sacra parishes, each quoad sacra parish would have its own kirk session but the heritors of the original quoad omnia parish(es) continued to act for civil purposes, at least in theory. However, different parishes tended to do things differently and the kirk session records themselves should be examined to find out the circumstances in any specific parish. The four cities (Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow) were especially prone to divisions and sub-divisions and the result was a large number of quoad sacra parishes in the cities, which is why they have been treated separately in the place search.

General sessions

The kirk sessions of quoad sacra parishes, especially in cities, could act together for a limited period of time or for certain purposes, sometimes in response to a crisis of some sort. These meetings of combined quoad sacra parishes were termed general sessions and equate either entirely or roughly with quoad omnia parishes but, again, it is not advisable to generalise about their purpose and functions.

Parishes quoad civilia

The term civil parish (or quoad civilia) is often used to refer to parochial boards (1845–1892) and their successors: parish councils (1892–1930). These were, strictly speaking, parishes quoad omnia, except that poor relief was now under the control of parochial boards. Later in the nineteenth century, parochial boards acquired public health and other civil functions. In a few cases after 1845, parochial boards were formed by statute for areas whose boundaries did not conform to those of previous quoad omnia parishes. In such cases, a place could be served by a quoad sacra parish (the kirk session acting as a church court), a quoad civilia parish (the parochial board acting for poor relief and public health purposes) and a residual quoad omnia parish (albeit with a rather empty title, wherein the heritors funded the maintenance of church buildings and clergy of several quoad sacra parishes).

Secession church congregations

From the eighteenth century onwards, a series of other Presbyterian churches were formed, mostly by breaking away from the Church of Scotland. These set up their own kirk sessions, presbyteries, general assemblies, and (in some cases) synods. It is best not to think of the kirk sessions for these churches as having parishes in the physical sense (as Church of Scotland kirk sessions and parishes had). The majority of these congregations re-joined the Church of Scotland by 1929 and the parish structure of the Church of Scotland was altered to make them quoad sacra parishes. If a congregation re-joined the Church of Scotland, the records should also (in theory) have passed to the Church and, if they survive, should be deposited in NRS or a local archive. In cases where a Presbyterian church congregation remained outside the Church of Scotland, its records are not covered by the agreement between NRS and the Church of Scotland, but might still be deposited in NRS or in another archive.

Presbyteries

Each presbytery superintends the kirk sessions and ecclesiastical activity within its boundaries, and also elects the ministers and elders to attend the annual General Assembly. As a court, presbyteries have the power of review over decisions taken by kirk sessions or congregations. Its membership comprises ministers, certain elders and (from 1990) members of the diaconate within its bounds. The presbytery’s main officials are a moderator (effectively chair), clerk and treasurer. Presbyteries meet more or less monthly. The General Assembly has the power to unite, disjoin or erect presbyteries. In the eighteenth century, there were 78 Church of Scotland presbyteries. In 2024 there are 41. The Presbytery includes amongst its tasks the oversight of records produced by each kirk session. Within each five-year period it will formally visit each congregation. Presbyteries have the duty of caring for the well-being of its ministers and candidates for the ministry.

Surviving presbytery records generally consist of presbytery minutes. These cover the full range of its duties, including oversight of its congregations and regular visitations to those congregations. They also cover the ordaining of ministers and their and their families’ well-being, the setting the boundaries of each parish for ecclesiastical purposes, and vindicating the Church’s claims to funds or property. The minutes will include formal examination of discipline cases and appeals against judgments of kirk sessions. Until the late nineteenth century the presbytery also examined parish schoolmasters before their appointment. In the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, presbyteries played a crucial role in raising and submitting petitions on regional and political affairs to civil and judicial authorities. There may be references to these activities in the minutes.

Synods

Synods were courts of the Church of Scotland which stood between presbyteries and the General Assembly. The General Assembly determined how synods were formed from constituent presbyteries. There were 15 synods in the eighteenth century, falling to 12 by 1930. Synods commonly met twice yearly and could hear appeals against decisions from presbyteries. They comprised all ministers and representative elders who were on the rolls of the presbyteries within the synods and there might also be ‘corresponding members’ from neighbouring synods. The main officials were a moderator (effectively chair) and a synod officer, as well as one or more clerks. Funds for their work came from an assessment levied on congregations within their bounds. Synod duties included examination of presbytery records, after which a report would be sent to the General Assembly touching on matters including the quinquennial investigation, special visitations of congregations (if required), and supervision of general schemes of the Church. The synod's own records would be examined by the General Assembly. Meetings of synods came to be poorly attended, in part because their authority was diminished, and they were dissolved from 1 January 1993.

Synod minutes include appeals for cases which had appeared before the constituent presbyteries, examinations of presbyteries’ record keeping, and examinations of presbyteries’ petitions or requests proposed to go to the General Assembly. Compared with the records of the presbyteries and kirk sessions, the synod minutes contain a relatively greater proportion of business relating to church policy and national events.

General Assembly

The General Assembly is the highest court and policy-making body of the Church of Scotland and it meets annually. Other Presbyterian churches have their own general assemblies. The acts of the General Assembly have been added to Scotland's People and like the kirk session records can be viewed using the Virtual Volumes search. The Assembly was first held in 1560, the year of the Scottish Reformation and saw the formation of the Protestant Church of Scotland. The primary business of the Assembly is to hear reports from the committees and councils, deliberate and decide church law and set the agenda for the national church. The Assembly also hears appeals which have been deferred from the kirk session courts and makes decisions on their outcomes.

Presbyterian churches in Scotland

Protestant churches in Scotland owe their existence to the European Reformation, which in Scotland’s case is usually regarded as occurring in 1560. For the next 130 years, the Scottish Church – and the Scottish nation – was riven (sometimes violently) by supporters of two competing forms of church government: Presbyterian (government of the Church by elected courts) and Episcopalian (government of the Church by bishops). This turmoil partly explains the poor survival rate of church court records between 1560 and the late seventeenth century.

Church of Scotland

Following the Revolution Settlement of 1690, the former Presbyterian party prevailed and the Presbyterian form of the Church of Scotland became the ‘Established Church’ (the official state religion). Although the majority of the Scottish population was in the Church of Scotland, it began almost immediately to lose members to other Presbyterian churches set up following various secessions. The largest of these was the Disruption of 1843. Thereafter there began a gradual coming together of the many Presbyterian congregations until finally in 1929 the United Free Church, formed from many of the seceding churches’ congregations, reunited with the Church of Scotland.

Secession Church 1733 ('Original Secession')

The 'Original Secession Church' was formed by Ebenezer Erskine, minister of Stirling, and three other ministers in December 1733. They were opposed to lay patronage and defended the claims of congregations to elect their own ministers. The Church split into Burgher and Anti-Burgher congregations in 1747.

The Reformed Presbyterian Church 1743

The Reformed Presbyterian Church had its origins in the followers of Richard Cameron (the ‘Lion of the Covenant’), known as Cameronians, who challenged King Charles II’s religious policy in the 1680s and rejected the Revolution Settlement of 1690. They were regarded as extreme Covenanters and remained outside the established Church of Scotland. Some joined the Original Secession Church, formed in 1733. Most of the remaining members joined the Reformed Presbyterian Church, set up in 1743, which itself merged with the Free Church in 1876. A tiny minority of members stayed independent of the Free Church and a few congregations still remain independent.

Burghers and Antiburghers 1747

The 'Original Secession Church', formed in 1733, split over the taking of the burgess oath (imposed by government following the 1745 Jacobite Rising), which required burgesses to acknowledge 'the true religion presently professed within this realm' (that is, the 'Established' Church of Scotland). The Associate Synod was the governing body of the Burghers and the General Associate Synod the governing body of the Antiburghers. Both the Burghers and the Antiburghers split later, the former in 1799 into 'Old Lights' and 'New Lights', the latter, also into 'Old Lights' and 'New Lights', in 1806.

Relief Church 1761 ('Second Secession')

The Relief Church was founded when Thomas Gillespie, minister of Carnock, and two others set up a presbytery ‘for the relief of the Christians oppressed in their Christian privileges’ following disputes over lay patronage. The Church was regarded as liberal, evangelical and anti-Covenanting. In 1847 the Church joined with the United Secession Church to form the United Presbyterian Church.

Burghers 1799

The Burghers, already a faction split from the Original Secession Church of 1733, split again in 1799, into ‘Old Lights’ and ‘New Lights’ over the role played by the state (‘the civil magistrate’) in religion. The Old Lights favoured the Church’s connection with the state and the Covenants and reunited with the Church of Scotland in 1839. The New Lights opposed connection with the state and the Covenants. They joined the New Light Antiburghers in 1820 to form the United Secession Church.

Antiburghers 1806

The Antiburghers, already split from the Original Secession Church of 1733, split again in 1806 into 'Old Lights' and 'New Lights'. The former approved of the Church's connection with the state and the Covenants and a majority of them joined the Free Church in 1852, leaving a remnant of the Original Secession Church to continue. The New Light Antiburghers joined with the New Light Burghers to form the United Secession in 1820.

United Secession Church 1820

The United Secession Church was formed from the union of the New Light Burghers and the New Light Antiburghers. It opposed state connection and was regarded as anti-Covenanting. In 1847 the Church joined with the Relief Church (the 'Second Secession Church’' to form the United Presbyterian Church.

Free Church 1843

The Free Church was founded in 1843 at the Disruption from the Church of Scotland, when the issue of lay patronage reached its climax, after a ten-year period of intense controversy. Led by Thomas Chalmers, 190 ministers left the Church of Scotland. Ultimately 474 ministers out of 1203 joined the Free Church, many of them ministers of Highland congregations. In some parishes a large number of the congregation followed them to join the new church. Some conservative members of the Free Church left it in 1892 to form the Free Presbyterian Church. The bulk of congregations of the Free Church joined with the United Presbyterian Church in 1900 to form the United Free Church, although a small number of Highland congregations remained independent.

United Presbyterian Church 1847

The United Presbyterian Church was formed in 1847 by the union of the Relief Church ('Second Secession Church') with the United Secession Church, itself a union, in 1820, of the New Light Burghers and the New Light Antiburghers. The United Presbyterian Church joined the majority of congregations of the Free Church in 1900, forming the United Free Church. A small number of Free Church Highland congregations remained independent.

Free Presbyterian Church 1893

The Free Presbyterian Church was formed by conservative members of the Free Church who believed it was becoming too liberal in its theology, in particular over what they considered to be the slackening of confessional standards. The majority of its congregations are in the West Highlands of Scotland.

United Free Church 1900

The United Free Church was formed by the union of a majority of congregations of the Free Church with the United Presbyterian Church. About 150 Highland Free Church congregations stayed out of the union, remaining independent. The United Free Church, apart from a remnant opposed to state connection and wanting greater theological liberty, joined the Church of Scotland in 1929. Thus this church, which was the successor to the majority of congregations of the seceding churches of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, joined again with the Church of Scotland.

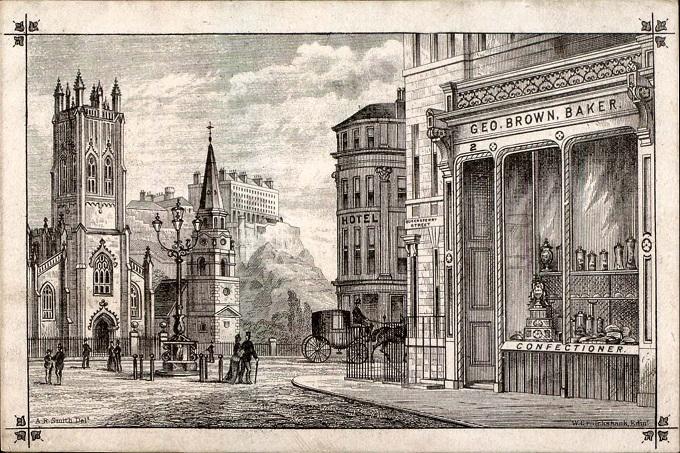

Illustrated trade card of George Brown, baker, looking towards the west end of Princes Street, Edinburgh, including St John's Church, 19th century

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, GD136/1340