Introduction

Sarah McCleary

Isabella Paterson

Euphemia Runciman

Further reading

Acknowledgements

Introduction

In October 2021, we published the article ‘The Fascinating Tales of the Devil’s Porridge and the Munitionettes'. In partnership with The Devil’s Porridge Museum, we told the story of three women who worked as part of the war effort in producing explosives for munitions in HM Factory Gretna, and appealed to our readers to submit their family connections to the factory to Laura Noakes (laura@devilsporridge.org.uk) at the museum.

We were delighted that the article received such a positive response and, as part of Women’s History Month (March 2022), we feature three women who we learnt about via this appeal, in order to tell their stories and the part they played during the First World War.

Sarah McCleary

The granddaughter of Sarah McCleary, Barbara Lees, contacted the Devil’s Porridge Museum after seeing our appeal to tell us the story of her grandmother.

Sarah was born on 2nd November 1886 in Rambank cottage in Kilmabreck, Kirkcudbright, to Peter, a clerk at a granite quarry, and Euphemia Josephs. After leaving school Sarah worked as a domestic servant, but with the arrival of the war she was employed as a nursing sister in the small on-site hospital which served the factory in Gretna.

Barbara explained that Sarah had been working as a Sister at the Fleming Memorial Hospital (the children’s hospital in Newcastle upon Tyne) before she moved to Gretna. An on-site hospital was necessary; one of the main components of cordite (which the factory produced) was acid and despite precautions there were a number of accidents. In some instances, workers' faces, hands and arms were sprayed with acid or they were overcome by noxious fumes. One of the risks for the women that worked on site, was the possibility of long-lasting harmful effects from the chemicals.

An example of one of the nitrating pans that women worked with which can be seen on display in the museum. Photograph taken in 2015.

Courtesy of The Devil’s Porridge Museum

A Volunteer Rescue Brigade was stationed nearby who were equipped with protective uniforms and stretchers to move workers to the hospital should there have been a large scale accident; thankfully that never happened.

An example of the uniform worn by onsite nurses, c 1917.

Courtesy of The Devil’s Porridge Museum

Barbara told us that: “When my husband and I visited the Gretna ‘Devil’s Porridge’ museum some years ago … we discovered from the lists of wartime inhabitants of the new town, that my grandfather Alexander Cunningham was living there too with his parents, Bernard and Elizabeth Cunningham …At Gretna Alec was a materials checker. I think Sarah and Alec already knew each other before moving to Gretna. They married in Creetown on December 7th 1916.”

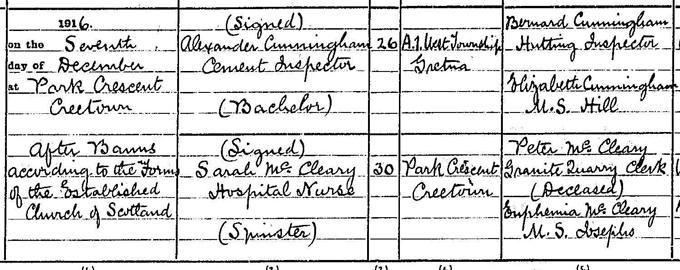

Detail from Alexander Cunningham and Sarah McCleary’s marriage entry, 7th December 1916.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland (NRS), Statutory Register of Marriages, 1916, 873/4

Their first child, Barbara’s father Ian Cunningham, was born at Gretna on 9th September 1918, just days before the end of the war. The family later moved to South Shields, England.

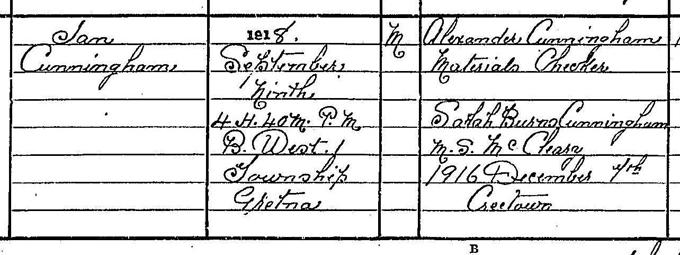

Detail from the birth entry of Sarah and Alexander’s first son, Ian Cunningham, 9th September 1918.

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Births, 1918, 827/69

A photograph of the hospital where Sarah worked, c 1917. It is not known if she appears in this image – Barbara Lees, Sarah's granddaughter, noted that she was camera-shy.

Courtesy of The Devil’s Porridge Museum

Isabella Paterson

Isabella was born in Birnie, Moray, on 10th August 1898 to James Paterson and his wife Jane Sutherland.

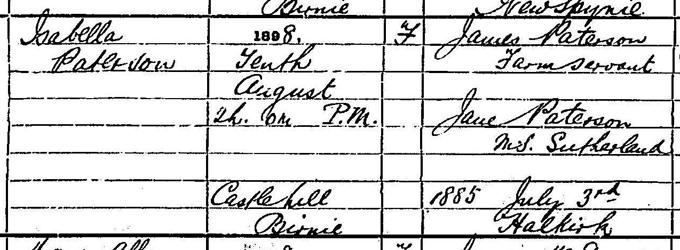

Detail from the birth entry of Isabella Paterson, 10th August 1898

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Births, 1898, 127/14

Isabella came from a large family of 12 siblings. Her father, James, was a farm servant from Latheron, Caithness, and raised his family with his wife on Spynie Farm, New Spynie, Moray. As a young woman, Isabella joined thousands of other women working shifts at the factory in Gretna to make munitions.

At the age of 18, on the morning of 2nd July 1917, Isabella finished a night shift. She returned to her lodgings at 36 Scott's Street and ate breakfast with her friend Williamina. The pair then proceeded to the shore at the Solway Firth to bathe in the sea. Upon entering the water the tides were low, however currents driving the sea to shore took the women by surprise and pulled them into a creek. Unable to swim they began to struggle. The Dumfries and Galloway Standard reported on 4th July that Williamina was able to scramble out and run to a nearby house to raise the alarm where she then collapsed. By the time help reached Isabella she had died. Her death entry lists her as an ‘explosives factory worker.’

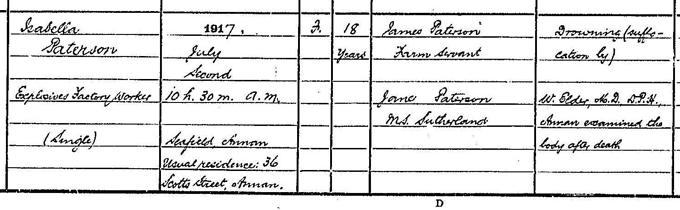

Detail from the death entry for Isabella Paterson, 2nd July 1917

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Deaths, 1917, 812/54

Euphemia Runciman

Euphemia, or Effie, as she was known, worked at the factory during the war. It is not known, at this time, the exact role that Effie worked in. Her relative, Graeme Hendry, holds a photograph of workers wearing traditional munitionette uniforms; it has not been confirmed if Effie is in this image but it is thought that she may be seen second from the right on the back row.

A group of munitionettes at HM Factory, Gretna, by Frank Holbrook, photographer at Alexander’s Studios, Dumfries and Annan, c 1917.

Courtesy of Graeme Hendry

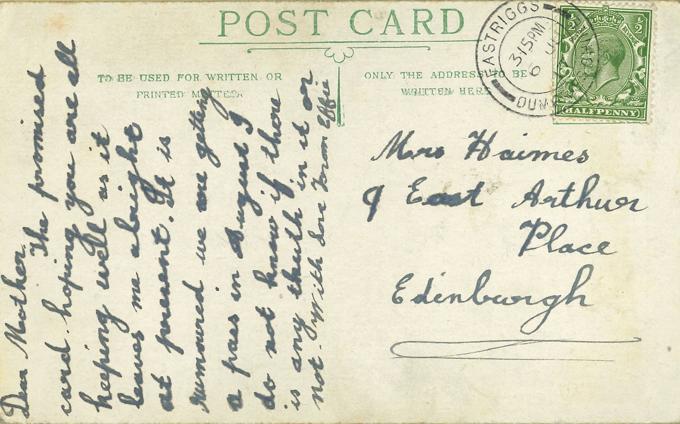

During her time at the factory, Effie wrote to her mother to say that her situation was ‘bright at present. It is rumoured we are getting a pass in August I do not know if there is any truth in it or not.’

The postcard written by Effie to her mother, 6th July 1917

Courtesy of Graeme Hendry

The munitionettes at Gretna worked on a three shift basis: 7am - 2pm, 2pm-10pm, and 10pm-7am. From 1917, the Home Office ruled that women should work a maximum of 60 hours per week, and 14 hour days could be worked on the condition that they were given breaks. The women did, however, have time to enjoy their wages, and going to the cinema or dance hall was a popular pastime.

Following the cessation of the war, Effie spent time in Edinburgh where she fell pregnant outside of marriage in the early 1920s. The societal shame of an unmarried pregnancy was felt by her mother, who cast her out of the family home and they became estranged. Her son, Robson Runciman, was born on 11th October 1920 at The Royal Maternity Hospital, Edinburgh. Sadly, he died just two months later on 11th December. Effie lived to be 93, spending her life out of contact with her relations – those surviving today only learnt about her, and the role she played in manufacturing explosives during the war, following her death.

Photograph of Euphemia Runciman, late 1910s

Courtesy of Graeme Hendry

Further reading

You can find out more at The Devil’s Porridge Museum's website.

Photograph of the exterior of The Devil’s Porridge Museum, Gretna, 2015.

Image courtesy of The Devil’s Porridge Museum.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to the families of Isabella Paterson, Sarah McCleary and Euphemia Runciman for helping us to tell their stories.