The National Records of Scotland (NRS) have made available a series of prisoner records from Edinburgh’s Bridewell and Calton Prisons between 1798 and 1851. These records reflect the shift towards a modern penal system and changing ideas around crime, punishment and society in the nineteenth century. This article sets out to give a history of this notorious institution, and place these newly released records in their social and cultural context and highlight some of the significant cases found within these files.

Calton Hill towers above Edinburgh, giving an astonishing vista of some of the capital’s most well-known streets, buildings and monuments and allows visitors to take in the splendour of the city’s new and old towns. Today, looking to the south, the view from Calton Hill is dominated by the Art-Deco-inspired St Andrew’s House. St Andrew’s House, a Grade A listed building, has served as the headquarters of the government in Scotland since it opened in 1939 and from 1999 onwards has housed the offices of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister of Scotland.

St Andrew’s House, built on the site of the old Bridewell and Calton Prisons (no date).

Image courtesy of the Scottish Prison Service

While St Andrew’s House is an imposing building in its own right, visitors to the same spot in the nineteenth century would have been greeted with a very different and altogether more terrifying sight; dominating the skyline was an extensive complex that looked like a medieval castle, complete with turrets and battlements. Indeed, many nineteenth century tourists arriving in the city by train, saw this edifice towering above Waverley station and assumed that this was Edinburgh’s famous castle.

Despite appearances to the contrary, the Bridewell Prison was a project of the Scottish Enlightenment, prompted by the social and prison reformer John Howard. Howard had himself designed an ‘ideal prison’, which later inspired Jeremy Bentham’s ‘Panopticon or Inspection House’ model of confinement. As the number of crimes for which capital and corporal punishment could be imposed was progressively reduced, imprisonment was increasingly used as an alternative.

Edinburgh Bridewell Prison (c.1840) with Edinburgh Castle in the background. Access to the prison was from the west (now Regent Road) before a bridge was built to connect Princes Street and the hill to the east. Adam’s version of a Panopticon is the semi-circular building in the centre of the image.

Image courtesy of City of Edinburgh Council - Edinburgh Libraries

Robert Adam offered six different proposals for the Bridewell and the one chosen for construction included a version of the Panopticon and yards for different gradations of prisoners relating to the seriousness of their crime. There were also considerations for the ventilation of the cells, and the daily duties of the prisoners from their morning meal to work (including spinning and weaving) or ‘hard labour’ during the day through to sleeping at night. This was undoubtedly a consequence of Howard’s influential publication ‘The State of Prisons’ published in 1777. The foundation stone was laid during a lavish ceremony on St Andrew’s day 1791 with Adam in attendance.

The Bridewell was the first of the new ‘reformed’ houses of correction to be built in Edinburgh and stood in stark contrast to the disorder of Edinburgh’s previous custody facilities at the Tolbooth on the Royal Mile. The desire for an orderly and structured environment and to manage the day to day activities of prisoners required the creation of a need to create extensive records for them.

The Bridewell took its name from a well dedicated to St Bride in London which was deemed to offer miraculous cures. Here a royal palace was built, which became known as Bridewell Palace and was handed over to the City of London by Edward VI. The palace then became a of refuge for vagrants, petty criminals, homeless children and women of ill repute. Bridewells began to appear all over Britain and to a certain extent this was the purpose of Edinburgh’s Bridewell.

It soon became clear that Adam’s building was inadequate to meet demand and the site was progressively expanded. The majority of Adam’s original designs (including the Panopticon) for the Bridewell were built over to incorporate the architectural plans of Archibald Elliot (1761-1823), creating what became Scotland’s largest custodial facility. The new Edinburgh Prison at Calton opened in 1817 and by 1859 the site had expanded to such a size that novelist Jules Verne described Calton Prison as resembling a self-contained medieval town. It was at this time that Calton Hill was first connected to Princes Street, as a bridge was built for access purposes to the jail.

Archibald Eliot’s structural changes to Adam’s design are portrayed here in this early photograph of the prison complex (no date).

Image courtesy of the Scottish Prison Service.

The Scottish Prison Commission employed General Thomas Bernard Collinson who also made further revisions to the prison in the 1880s.

Those incarcerated within the prison did not share Verne’s sentiment and across the years, Calton Prison acquired a reputation as Scotland’s harshest prison. One of its later prisoners, Trades Union activist Willie Gallacher, was detained in Calton Prison for sedition during the First World War and described it as ‘by far the worst prison in Scotland; cold, silent and repellent. Its discipline was extremely harsh, and the diet atrocious.’ Gallacher would be among the last generations to experience the hardships associated with Calton Prison. Shortly after the end of the First World War, HMP Edinburgh – better known as Saughton – opened in the suburbs of Stenhouse, and Calton Prison demolished to make way for the new Scottish Office building. All that is left of this astonishing building is the former Governor’s House, which is constructed in the same castellated style and some of the old prison walls which can be seen from Calton Road, between Waverley Station and the base of Calton Hill.

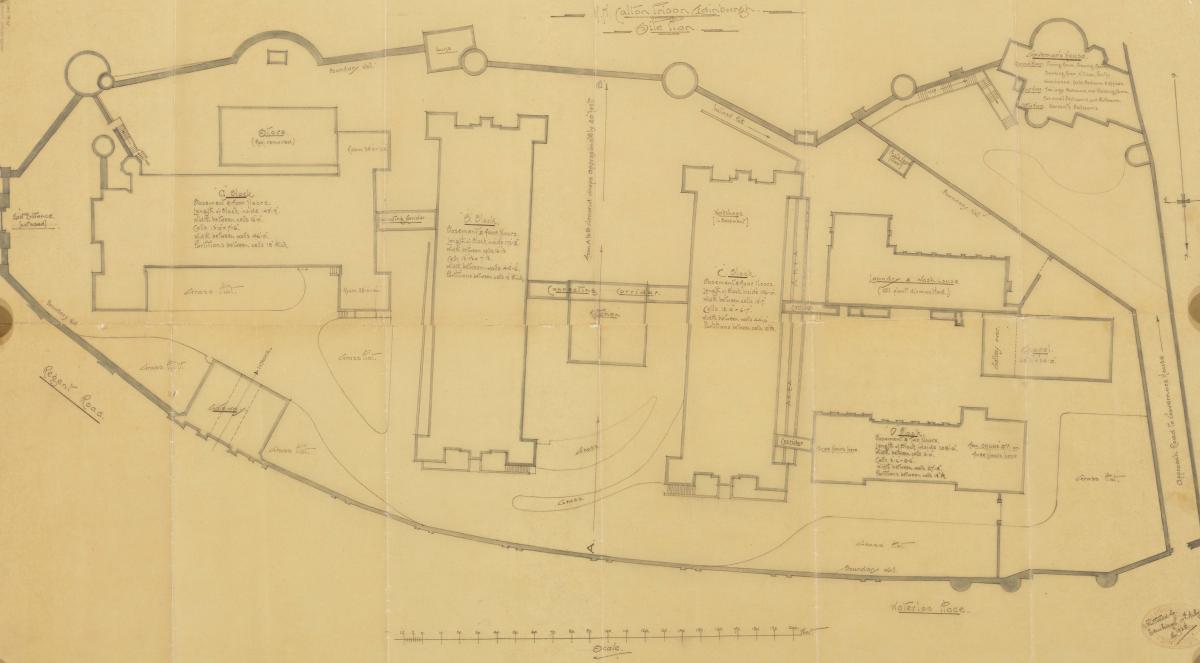

Plan of Calton Prison, 1928.

NRS, RHP43986

Prisoner profile: James Cumming, Chartist

But what of the men, women and children who were incarcerated in Calton and Bridewell Prisons over the years? The prison registers, searchable on Scotland's People reveal people from across the social spectrum were incarcerated for a variety of offences from 1798-1851. The imprisonment of Gallacher was not the first time that Calton Prison had been used to house political dissidents.

In the aftermath of the Great Reform Act of 1833 that failed to extend the vote to the working classes, organisations predominantly in the new industrial areas of England, Wales and Scotland held mass rallies and collected petitions in order to demand universal male suffrage, secret electoral ballots and parliamentary constituencies of equal size. These ideas spread widely in lowland Scotland and by the late 1830s there were over 150 Chartist groups in existence. These reforms were bitterly contested and the Chartist leaders persecuted by the authorities. This concern reached its height in the aftermath of the revolution in Paris of 1848 and a number of Chartist meetings were violently suppressed.

One person to fall foul of this legislation and was also charged with sedition, was the Edinburgh Chartist leader James Cumming. The evidence against Cumming comprised a series of ‘criminal letters’ written to other Chartist leaders about obtaining arms and organising meetings in Edinburgh to gain new members and rouse the current ones. Unfortunately, these letters (submitted as evidence in court) were delivered to someone with a similar name and address and he handed in the letters to the police. Edinburgh-born Cumming admitted in his declaration before the High Court, that he was a member of the Stockbridge section of the National Guard, a Chartist movement in Scotland, but that it had been dissolved some time before (NRS, High Court of Justiciary papers, JC26/1848/511). He went on to state that he knew nothing of an order to raise arms for its members and that if he had written letters to a fellow Chartist leader in Glasgow, it had not been since the National Convention (which took place in March 1848).

Along with Cumming, Henry Ranken, John Grant and Robert Hamilton were also charged with sedition. However, a legal challenge of the Indictment against Cumming by his legal representative meant that he was dismissed from the trial and freed from Calton Prison along with Grant. However, their alleged co-conspirators, Ranken and Hamilton, were not so lucky. Each of the jury found them guilty of ‘using language calculated to excite popular disaffection and resistance to lawful authority’ (Perthshire Advertiser, 15th November 1848). They were sentenced to four months imprisonment.

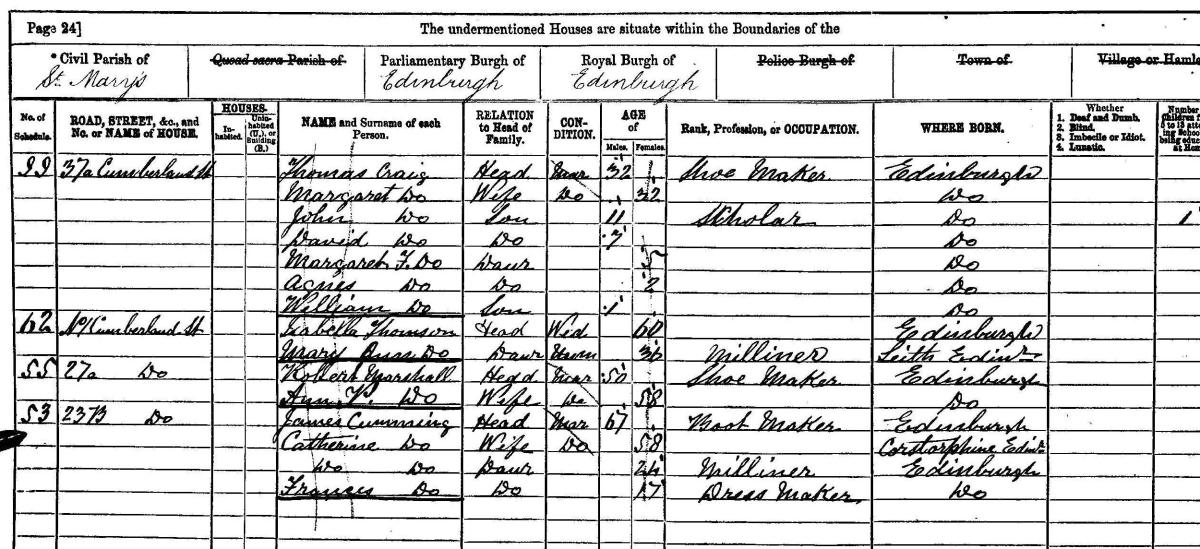

James Cumming died in 1888 at the age of 86. He can be found in enumerated in the census records of 1851,1861, 1871 and 1881 as a ‘shoemaker’ or ‘bootmaker’ and his final place of residence was in Stockbridge, now a gentrified area of north Edinburgh.

James Cumming lived out his later years at 23B Cumberland Street, Stockbridge, Edinburgh. In the 1871 census, his daughters were enumerated living at home and employed in the city.

Crown copyright, NRS, 1871 census, 685/2 41 page 24

Prisoner profile: John Kerr, Body snatcher

The late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries saw Edinburgh emerge as a centre of medical and anatomical knowledge. However, strong religious and legal objections existed to using corpses for dissection. These tensions created a particular challenge for schools of anatomy and a thriving trade emerged in exhuming recently buried corpses in order to sell them to anatomists. Most notorious among these so-called resurrectionists, were William Burke and William Hare, who moved onto murdering their victims in order to sell their corpses.

In 1829, John Kerr, James Barclay and George Cameron were charged with ‘violating of sepulchres of the dead’ the legal term for removing dead bodies from a grave. The corpses they carried away from Lasswade Kirkyard - a village 14.5 km south of Edinburgh city centre - belonged to Alexander Kerr, a child of 21 months, Joan Swann, a village resident, and John Braid, a labourer in the parish. These bodies were buried during the month of January or early February 1829 but on the night of the 20th February or early morning of 21st February 1829, their graves were ‘wickedly and feloniously opened and the said body carried away’ (NRS High Court of Justiciary papers, JC26/1829/2679). The same charges were also brought against Helen Begbie or Miller, who is thought to have informed Kerr and his associates of the location of recent burials in Lasswade Kirkyard. It is thought that charges against Miller were dropped as she turned informant on Kerr, Barclay and Cameron. Kerr was made an example of by the court and sentenced to nine months hard labour, serving 274 days.

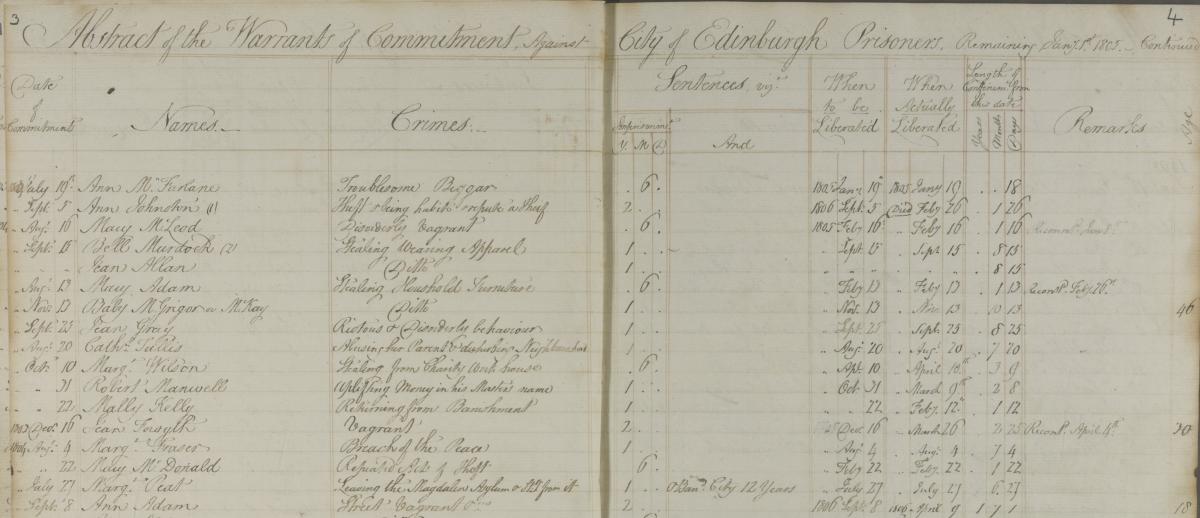

The early prison registers of the Bridewell reflect the fact that it was not only home to adult male criminals; its original purpose was also to house vagrants and wayward children. The admission registers of 1798-1790 are brief and contain the prisoner’s name and their dates of admittance and liberation (a prisoner’s criminal offence is recorded in the registers from 1805). The prisoners are more commonly women, charged with being drunk and disorderly or returning from banishment, and children charged with petty crimes.

A page from the Bridewell Prison register for 1805. The first entry on the page is for Ann McFarlane charged with being a ‘Troublesome Beggar’. The majority of entries on this page are for women charged with minor offences such as vagrancy and being drunk and disorderly.

Crown copyright, NRS, HH21/6/2 page 4

Another sad case from 1805 can be seen in the registers concerning an 18-year-old woman Mary Downie. Downie did not appear to have been named in the Warrant for her arrest but is imprisoned for ‘Drunkeness & great Neglect of Duty towards her infant Child’. It is not clear whether the child was imprisoned with her, however, she spent three months in the Bridewell. These pages in the register also give us an idea of prisoner numbers for this period, as noted at the end of the prisoner list:

Bridewell prison register with totals of prisoners admitted and liberated in 1805. Mary Downie was admitted on 19th September of that year.

Crown copyright, NRS, HH21/6/4 page 10

Children can frequently be found in the Bridewell registers, including children as young as five, largely on charges of theft and vagrancy. One Hugh McDonald, admitted on 13th March 1811, aged 13, served 30 days for the crime of ‘Cutting on two panes of glass & stealing from a shop window’ (NRS, HH21/6/2 page 106). Charles McLaren, aged six, and Ann McLaren, aged eight, (presumably brother and sister) were admitted to the Bridewell on 23rd April 1814 on a charge of ‘Theft’ and were given only ‘bread & water’ during their 14 days’ confinement.

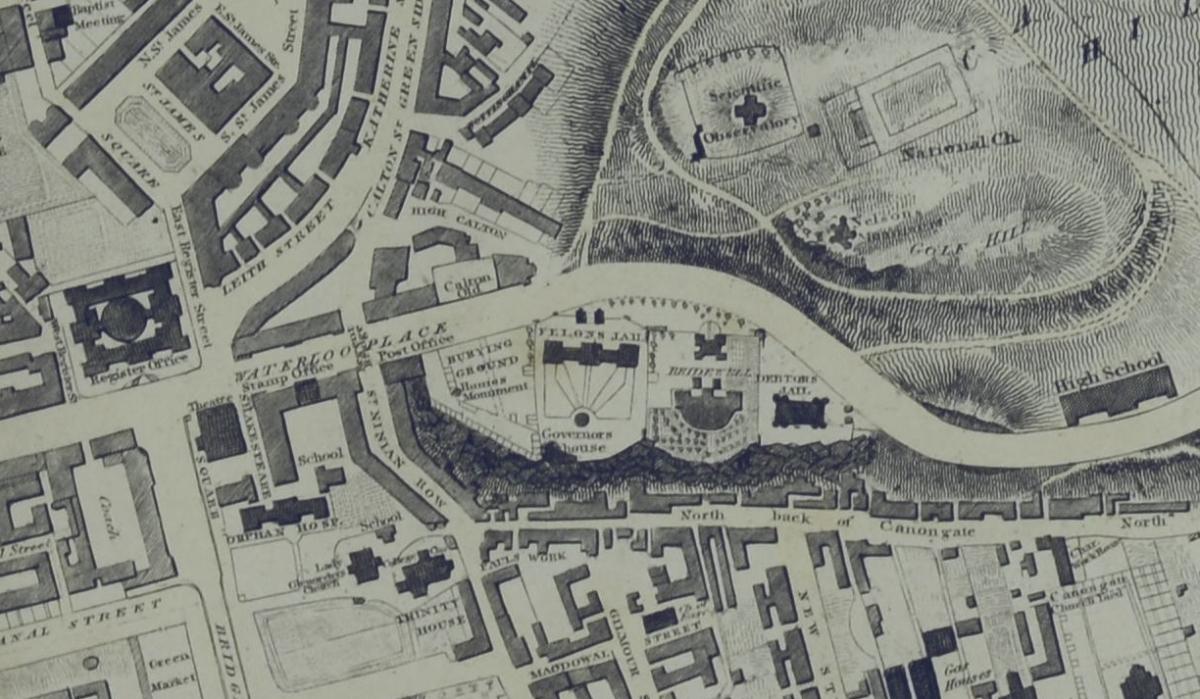

Plan of Edinburgh City by John Wood, 1820. The Bridewell, including its Panopticon, can be seen with its semi-circular shape. The ‘Felons’ Jail’ is also depicted to the west of the Bridewell complex.

NRS, RHP13044/16

Bridewell Prison's role in housing those who were exhibiting problematic, rather than criminal behaviour began to change. We see this most clearly in the treatment of women who worked as prostitutes. By 1797, a Magdalen Asylum was founded in Edinburgh which could accommodate 12 carefully selected women released from the Bridewell (or elected elsewhere) and give them paid work rather than see them return to sex work. Upon leaving the Asylum, many of the women found employment in domestic service and others returned to estranged families. Maria Hutchison, born in Ireland, was a frequent ‘guest’ at the Bridewell:

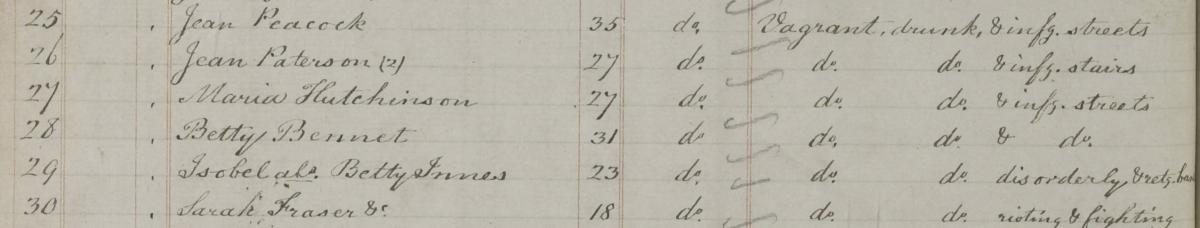

Extract from Bridewell Register, showing Maria Hutchison, aged 27, was admitted on 20th August 1821 for being ‘vagrant, drunk & infesting the streets’. She appears here amongst a list of women with similar charges against them.

Crown copyright, NRS, HH21/6/4 page 119

Hutchison is recorded in the Bridewell registers for similar offences on 23rd December 1820 and 4 June 1821, commonly serving 20 days imprisonment. The Magdalen Asylum must have considered her a needy case and gave her sanctuary on her liberation in September 1821. However, she was back in the Bridewell on 1st December on charges of being’ drunk and inf[esting] P.[ost] Office’ (HH21/6/4 page 128).

By drawing out these individuals from the registers, we can see how the jails and the life stories of their prisoners reflect the dynamic period of change Edinburgh and Scotland were experiencing. The prison registers reflect the social changes of the eighteenth and nineteenth century Scottish cities and are a rich source of information for family and social historians alike.

For more information about prison registers and how to search them, please see our guide on prison registers on Scotland's People.

We have also updated our glossary of abbreviations, words and phrases to include terms found in the prison registers.