What can I learn from wills and testaments?

How to search wills and testaments

Understanding the content of wills and testaments

Background information

Testaments provide information about how people lived in the past: how they dressed, furnished their homes, conducted their affairs, the tools of their trade, what land they owned, the crops they grew and, in the 19th century, which public utilities they invested in and which railway companies they owned shares in.

Will

A will is the document drawn up by an individual wishing to settle his or her affairs prior to death. It sets out instructions for the disposal of their possessions.

Testament

A testament is the legal document drawn up after a person has died, to enable the court to confirm an executor who would be responsible for winding-up the deceased's affairs. Every testament includes an inventory of the dead person's property. This may be a brief summary valuation of the goods involved, or it can be a long list of individual items and valuations.

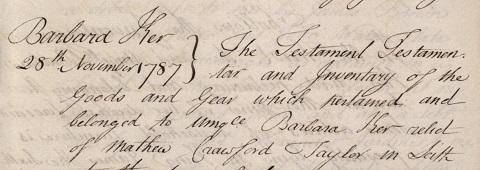

Testament testamentar

The testament testamentar applies when the deceased died testate (leaving a will). It comprises four parts:

- the introductory clause;

- an inventory of the deceased's possessions (see below);

- the confirmation clause and a copy of the will, stating the wishes of the deceased regarding the disposal of the estate and naming the executor (usually a family member) he or she had chosen to undertake this task. If a copy of the will is not included, reference will be made to its recording elsewhere, probably in the court's Registers of Deeds.

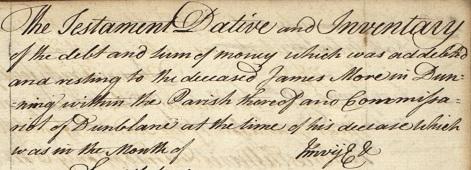

Testament dative

The testament dative is drawn up by the court if a person died intestate (without leaving a will), in order to appoint and confirm the executor on their behalf. It comprises three parts:

- the introductory clause;

- an inventory of the deceased's possessions;

- the confirmation clause.

The testament dative might name a family member or a creditor as executor, but if the deceased died in debt, a creditor might be appointed as executor instead. In such cases, the testament includes a list of the deceased's debts.

Inventory

An additional inventory is a supplement to a testament, added some time later, to extend the confirmation of an executor to cover property not originally included.

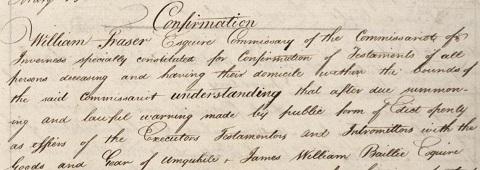

Confirmation

The confirmation is the document granted to the executor(s) of a deceased person when the court has registered the inventory of the estate and will (if one was made). It signifies that the inventory has been accepted as correct and that the will was valid.

What can I learn from wills and testaments?

The testament testamentar is more useful to family historians than the testament dative because of the inclusion of the will. Executors are usually family members and other family names might appear as beneficiaries, although not necessarily the spouse or children. Since they are already catered for under the 'widow’s part' and the 'bairns’ part' of the moveable estate, the spouse or children might only be named in the will if they are to benefit from the 'dead’s part' in addition to their lawful share of the estate.

A testament dative contains no will, but the court often named a close family member as executor. However, if the deceased died in debt, the court might appoint a creditor as executor instead. In the latter case, it is less likely that family names will be included.

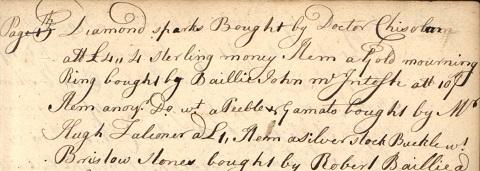

Almost every document in the wills and testaments index contains an inventory of some kind, except where there are separate registers for wills. The inventory lists the moveable property belonging to the deceased at the time of his or her death. It can include household furnishings, clothes, jewellery, books, papers, farm stock and crops, tools and machinery, money in cash, bank accounts and investments, as well as money owed to creditors and money due from debtors. Often the inventory consists only of a brief, overall valuation, but sometimes it is very detailed, with the value of every item listed. As such, it can supply a snapshot of the deceased's lifestyle and help to build up a picture of what social and economic conditions were like in a particular locality at a particular time. An inventory that contains a 'roup roll' is particularly interesting in that it itemises each lot sold in the auction and states the prices paid (sometimes with the names of the purchasers).

Family names may or may not be included in wills and testaments. If your ancestor owned heritable property, that is, land, buildings, minerals in the ground and mining rights, this would automatically be inherited by his eldest son, in accordance with the Scottish rules of succession. Therefore, unless he was also to receive a legacy under the terms of his father's will (a copy of which should be included in the testament) do not expect to find any reference to him.

Even if your ancestor did not own any 'heritage', you may not find the names of all his offspring because his children were, by right, entitled to a third part of his estate if their mother was still alive, or a half if she had pre-deceased her husband, and there was no need to mention this share (termed the 'legitim') in the testament. The beneficiaries of the 'dead's part' will be named in the will, however, so if any children were to benefit over and above their 'legitim' share you will find them here.

If your ancestor was poor, it is unlikely that he or she made a will. It is worth checking the index though, to see if a testament dative is recorded. The latter relate to the estates of people from all walks of life. The inventory clause can include such items as haystacks and bottomless chairs!

When wills and testaments were recorded in the Commissary or Sheriff Court, the documents were copied by a clerk. Most wills therefore are not in the handwriting of the deceased. There are certain exceptions to this rule, for example soldiers’ and airmen’s wills, where the deceased’s written will may have been preserved. Consult our guide on soldiers' and airmen's wills for more information.

How to search wills and testaments

The wills and testaments index contains over 611,000 index entries to Scottish wills and testaments dating from 1513 to 1925.

Go to search the records - legal records - wills and testaments. You can search on some or all of the following index fields:

- Surname

- Forename

- Year range (the date that the testament was recorded)

- Description - by title, occupation or place (where these are given)

- Court or commissariot in which the testament was recorded

The search form includes tips for each field with links to more detailed research guides where appropriate.

Index entries do not include names of executors, trustees or heirs to the estate. They also do not include the deceased's date of death, nor the value of the estate.

Sometimes the intervention of the court to settle the deceased's affairs was not required until many years after the death, possibly due to a dispute, therefore if a will or testament exists, it may be recorded much later than you would expect.

Please bear in mind that there was no legal requirement for individuals to make a will. Even if someone died intestate (that is without having made a will), there was no obligation for the family to go to court to have the deceased's affairs settled.

Wills and settlements are also found in the Register of Deeds (Books of Council and Session). It may therefore be worth your while contacting the Historical Search Room at the National Records of Scotland (NRS), who hold these registers, to see if they can assist you further

Understanding the content of wills and testaments

Property and inheritance

Under Scots Law, an individual's property was divided into two types:

- Heritable property consisted of land, buildings, minerals and mining rights, and passed to the eldest son according to the law of primogeniture.

- Moveable property consisted of anything that could be moved, for example, household and personal effects, investments, tools, machinery.

All children had equal rights to the deceased’s moveable property. When the deceased’s property was being distributed it had to be divided into a maximum of three parts:

- the widow's part - jus relictae

- the bairns' part - legitim

- the dead's part - deid's part

If the man had been pre-deceased by his wife the division was into two parts: the bairns’ part and the died’s part. If the man had no surviving wife or children the whole of his moveable estate was designated as the deid's part. The deceased could only specify the disposition of the died’s part.

Heritable property went by right to the eldest son, which automatically debarred him from receiving a share of the moveable estate, that is the share which formed part of the legitim. However, this son was still entitled to the heirship moveables so that he would not succeed to a house and land completely denuded. These moveables consisted of the best of the deceased father's furniture, horses, cows, farming implements and so on.

The moveable estate of a widow would be divided into two parts, the legitim and the deid's part.

Eiks

Before 1823 you may find that in addition to a testament there is an eik. This is a supplement to a testament, added some time later, to cover property not originally included. You will sometimes find several eiks relating to the original testament.

In the registers of inventories there are sometimes also additional inventories, which are the equivalent of eiks.

The information in each of these documents will be different.

Ultimus haeres estates

An ultimus haeres estate is one where a relative has died without a will or a known relative and whose estate has consequently fallen to be administered by the Crown. Further information can be obtained from the King's and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer (KLTR) website.

English probate recorded in Scotland

Probate or Letters of Administration are words for documents in English law relating to wills. In the registers of testaments they relate to Scottish people who died in England or British colonies abroad. If they left a will probate was granted by the English courts. If they died intestate letters of administration would be issued by the court for the appointment of executors. These documents occur mainly in the registers of Edinburgh Sheriff Court. Some are copied into the register, but others are merely noted as having a copy lodged with the court. These copies, starting in 1858, are in the records series of Copy Probates Resealed in Edinburgh Sheriff Court (National Records of Scotland, SC70/6), which have also been digitised.

The words 'non-Scottish Court' in the Court column of the results show that a copy probate exists for that person.

Language and handwriting

Some earlier wills and testaments are difficult to read. Look at the guides on reading older handwriting, unfamiliar words and phrases and search the glossary for assistance with abbreviations, legal terminology, occupations and other unfamiliar words. Guidance is also provided on agricultural produce and livestock, dates, numbers and sums of money and weights and measures.

Wills registered after 1925

Wills registered between 1925 and 1999 have not been digitised and may only be consulted in the Historical Search Room at NRS. The printed Calendar of Confirmations is the yearly index to these wills. See the NRS guide on wills and testaments for further information.

Wills dating from 2000 have not yet been transferred to NRS. For further information you should contact the Commissary Department, Edinburgh Sheriff Court, 27 Chambers Street, Edinburgh EH1 1LB.