History of Perth Prison

Prisoner profile – Suffragette Arabella Scott

Prisoner profile – George Chalmers

Prisoner profile – John Evelyn Barlas

Further reading

The recent release of 2,175 images from the Perth Prison registers on Scotland's People affords us the opportunity to explore in more detail the rich and diverse history of the prison. We will also highlight some fascinating case studies of three individuals who were imprisoned there.

History of Perth Prison

There has been a gaol at Perth since at least the thirteenth century, with a larger prison complex, known as the ‘Perth Depot', built by French Napoleonic prisoners of war between 1810 and 1812. This construction operated as a depot for 700 prisoners, some/many of whom would occupy themselves by making items to sell at the weekly market. The paroled French soldiers often stayed within the city with local families and were accepted into the community. In 1815, after the Battle of Waterloo, there was an effort to repatriate the French soldiers and they were waved off by thousands of local Perth residents having built up a good relationship with them during their imprisonment.

In 1839 the depot was selected as a civilian prison, with the first phase completed to designs outlined in the 1839 Act to Improve Prisons and Prison Discipline in 1840. Perth Depot was designed by Robert Reid (1774–1856), surveyor to the King in Scotland, 1808–40, and comprised five barrack blocks emanating from a central observation tower. The former prisoner accommodation was demolished, with the original perimeter wall, central tower and office buildings at the front of the site retained.

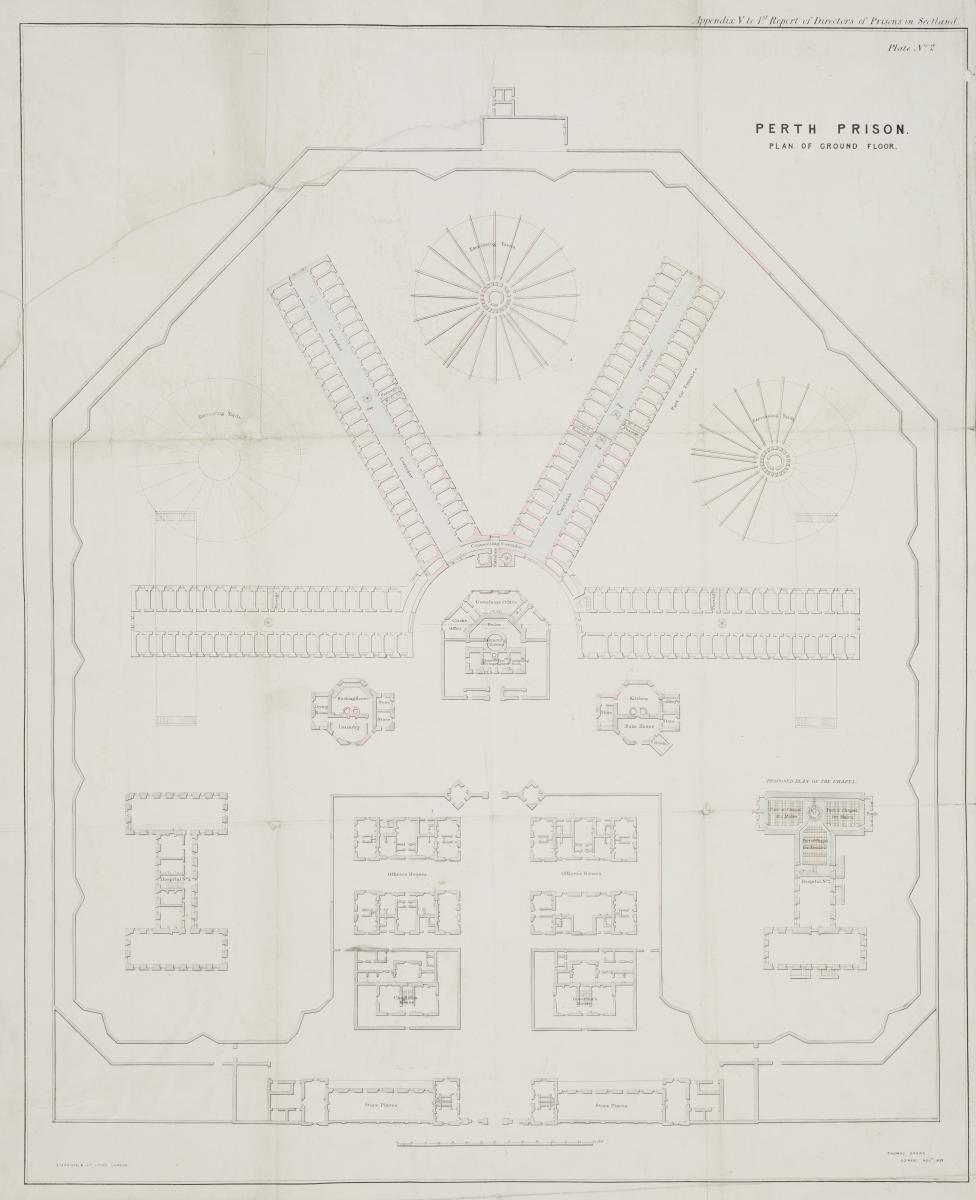

Plan of ground floor of Perth Prison, produced as part of a report of the Directors of Prisons of Scotland, 1839.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland (NRS), RHP9270/2

This plan of Perth Prison depicts the principles of contemporary prison reform favouring the separatist method of imprisonment. This involved distinct cells for different social classes and sexes, a specified space for exercise, and the monitoring of prisoners by paid gaolers.

Prisoners using one of the exercise yards at Perth Prison. Late 19th century.

Credit: Scottish Prison Service

Purpose-built prisons (for the function of confinement) were first constructed in Scotland in the late eighteenth century. Before this time, imprisonment was not formally used as a type of punishment and prisons or gaols served a purely custodial function before a debt was paid, transportation (which came to an end in 1857) or execution.

Before the 1839 Act, the management of Scottish prisons belonged to the burgh and conditions were variable. There were exceptions: Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen were built by county magistrates under a local act of parliament and conditions were improved. These improvements included better cell ventilation, drainage, prisoner diet, visitation rights, prevention of escapes, provided clothing, exercise and duties of medical and religious staff.

The 1839 Act bestowed general superintendence of all Scottish prisons into the hands of the General Board of Directors of Prisons in Scotland. County Boards were established which took over the local management of all prisons except the General Prison. This was set up in Perth and administered directly by the General Board of Directors as a government institution for the detention of criminals undergoing long sentences. The General Board was abolished by the Prisons (Scotland) Act of 1860, and its responsibilities for local prisons passed to the Home Secretary.

The running of the General Prison was entrusted to four managers: the Sheriff of Perth, the Inspector of Prisons in Scotland, the Crown Agent and a stipendiary manager. The County Boards had thereafter to report to the Home Secretary. The Managers of the General Prison at Perth formed the Board of Management of Prisons in Scotland and acted as advisors to the Home Secretary on all matters relating to prisons in Scotland.

Under the Prevention of Crimes Act 1871, the Secretary of the Managers of the General Prison became responsible for keeping the register and photographs of criminals in Scotland. The Managers were required to report annually to the Home Secretary.

In 1877 the administration of prisons in Scotland became the responsibility of the Prison Commission for Scotland.

Detail from plan of Perth Prison, Perthshire: Ordnance Survey 1/2500 plan (Perthshire, XCVIII.9). This image shows how the prison was at the centre of Perth’s community, located next to the railway line which was built shortly after the remodelling of the prison which took place 1840-42.

Crown copyright, NRS, RHP9269/1

Prisoner profile - Suffragette Arabella Scott

Perth Prison is currently the oldest occupied prison in Scotland and, as we have seen, it has had an interesting and varied history. It was the second prison to have the facilities to force-feed hunger striking suffragettes (Edinburgh Calton Gaol being the first). On 19th May 1913, Arabella Charlotte Scott was convicted of attempted fire-raising and sentenced to nine months’ imprisonment.

Arabella Charlotte Scott’s entry in Perth Prison’s admission register of 20th June 1914.

Crown copyright, NRS, HH21/47/14 page 68.

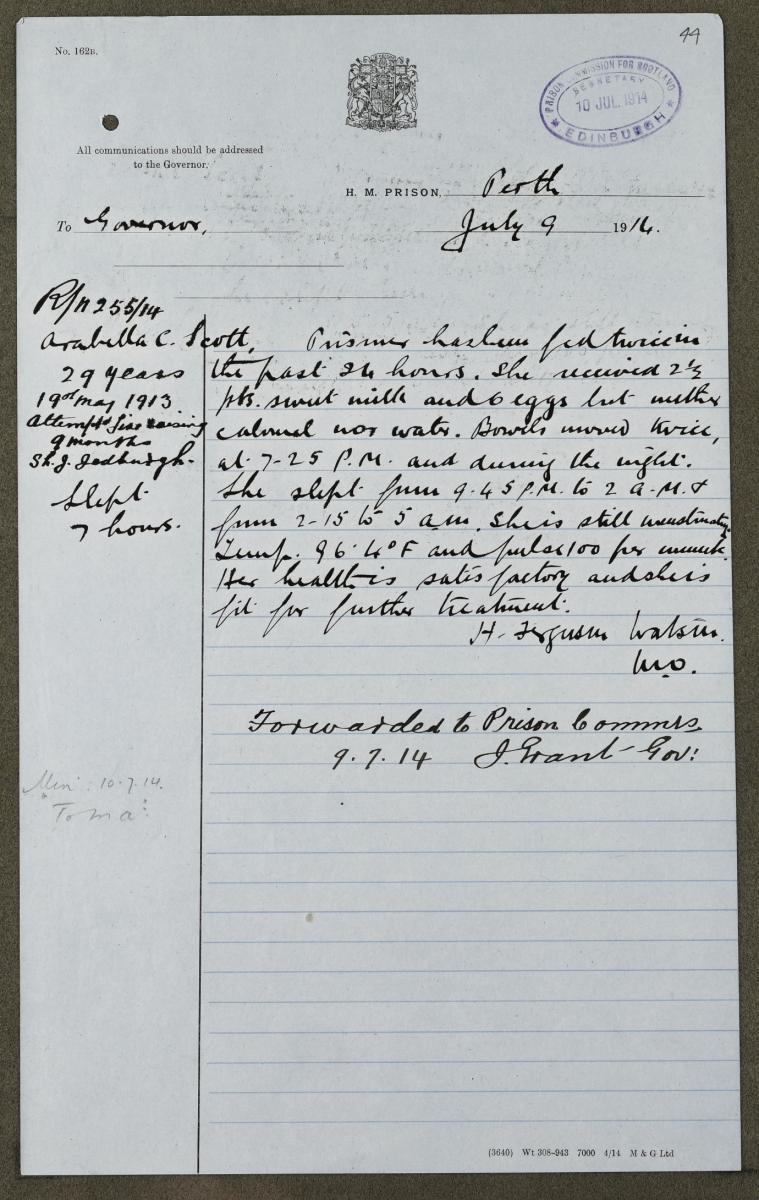

Admitted to Calton Gaol, she immediately went on hunger strike, and later that month was released under the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act, more commonly known as the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’. Scott was re-arrested and released repeatedly over several months, before finally being re-arrested on 18 June 1914 and transported. While imprisoned at Perth, Scott was force-fed using a tube introduced to her stomach from 20th June until 26th July 1914.

A page from prisoner Arabella Charlotte Scott’s file, detailing her detention at Perth Prison. It notes that Scott slept for seven hours and had been force fed sweet milk and eggs.

Crown copyright, NRS, HH16/44

Less than a month after Scott’s imprisonment on 10th August 1914, the Secretary of State for Scotland announced the mitigation of all suffragette sentences passed in Scottish courts, including Scott's.

Prisoner profile – George Chalmers

The violent and bloody murder of John Miller on 21st December 1869 at Braco, Perthshire, led to the first execution behind prison walls in Scotland under the Capital Punishment Amendment Act 1868. Vagrant George Chalmers was found guilty of the murder of the tollbooth keeper and was hanged on 4th October 1870 at Perth Prison.

Chalmers maintained his innocence until the end. Reverend McLaren, in Chalmers’ hometown of Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire submitted two petitions with a total of 600 signatures to the Home Secretary pleading for the sentence to be reduced on grounds that the evidence was inconclusive and Chalmers was not of sound mind.

Despite Chalmers' protests of innocence, and attempts to save Chalmers’ life by locals of his hometown, he was hanged on a scaffold built outside the Governor’s House at Perth Prison on 4th October 1870. The Dundee Courier reported on the day of the first Scottish private execution with great detail:

The privacy with which all executions are now effected has been marked in the present case. All the necessary preparations were completed almost without any one knowing about them; and so far as the appearance of the town last night concerned, the streets being as quiet as usual, no stranger would have been led to suppose that on the morrow the horrifying spectacle of an execution was to take place. Dundee Courier, Wednesday 5th October 1870

The reporter witnessing Chalmers' last moments went on to describe the condemned man’s last words:

The rope having been finally adjusted, the grey-bearded executioner draws from his pocket the hideous white cap, and pulls it over the head of the culprit, shutting out for ever from his sight everything pertaining to this world. [Chalmers said] in a loud and firm voice – “May the Lord have mercy on me. Good-by with you all. Farewell for evermore. Thank God, I am innocent.” The words has hardly escaped from his lips when the hangman grasped the hand of the victim as a last farewell, and with a sudden jerk the bolt was drawn. Dundee Courier, Wednesday 5th October 1870

A black flag was raised above the prison wall to indicate that the execution had been carried out. Chalmers was buried in an unmarked grave in the prison grounds.

Handbill £50 reward notice for George Chalmers, from the precognition papers created for Chalmers' High Court trial.

Crown copyright, NRS, AD14/70/250

Three more executions took place at the prison, in 1908, 1909, and 1948.

In 1965 a new purpose-built execution shed was completed. However, this new facility was never used for its intended purpose as the Murder Act 1965 abolished capital punishment for murder and instead the building was used as offices and a training facility until demolished in 2006. The introduction of the Capital National Records of Scotland Punishment Amendment Act 1868 saw public executions come to an end.

Prisoner profile - John Evelyn Barlas

John Evelyn Barlas (1860–1914) was born in Rangoon, Burma, but spent his early life in Glasgow and later moved to London. Barlas was a political activist and poet, and while studying at New College, Oxford, became friends with Oscar Wilde. Barlas’ family had connections with Crieff, Perthshire, where he would often visit.

After graduation in 1884, Barlas took up several teaching posts in Ireland and England and was regarded as an inspirational teacher. He married Lord Nelson’s great grandniece, Eveline Honoria Nelson Davies (1861–1934), also born in Burma, with whom he had two children. It was during this period of his life that he began to write prose, although his radical left-wing sympathies were not reflected in his poetry.

Barlas received a head injury during the ‘Bloody Sunday’ demonstrations in 1887, and would go on to experience episodes of delirium and depression for the rest of his life. After discharging a revolver at Speaker’s Green, outside the House of Commons, displaying his contempt for parliamentary democracy, he was swiftly arrested. Following two weeks in custody, his friends Oscar Wilde and fellow socialist activist Henry Hyde Champion settled his bail terms and he was released.

Returning to Crieff, sometime after his release, he was arrested again on 12th September 1892 for assault, but was removed to a mental health hospital soon after. Barlas had assaulted a London journalist called Reginald Booker by striking him on the head. He had also assaulted James Stewart of Crieff during the same skirmish. Barlas was apprehended after a ‘violent struggle’ with three policemen. (Leeds Times, Saturday 17th September 1892)

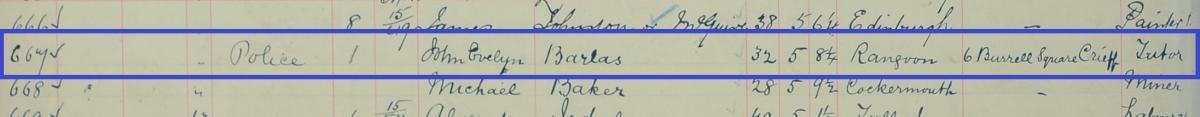

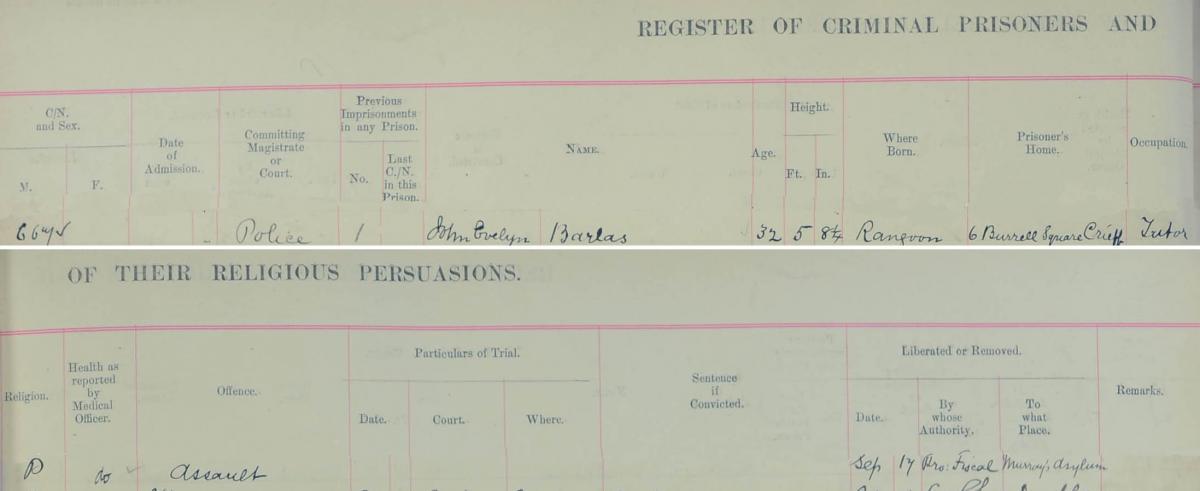

Extract from Perth Prison admission register, 1892. Barlas is imprisoned on the charge of assault, but is transferred to James Murray's Royal Lunatic Asylum at Perth.

Crown copyright, NRS, HH21/47/6 page 45

Barlas appears in Perth Prison’s registers again in July 1894. He has been charged with assault and breach of the peace (B & P). The incident for which he was charged was reported widely in British newspapers. The sensationalist headline in the Scotsman read ‘Extraordinary Scene With An Anarchist in Crieff’ and went on to state:

In Crieff – John Evelyn Barlas (34), B.A. of Oxford, residing in Burrell Square, Crieff was brought up at Crieff Police Court on Saturday on a charge of having committed an assault the previous day. […] The accused, on being seized hold of, knocked down one or two of the constables, and otherwise offered a strenuous resistance when taken hold of. [Barlas] was removed to jail, shouting loudly that he was an Anarchist, and calling his captors “a pack of Scotch dogs” and threatening to yet do for them. The Scotsman, Monday 23rd July 1894

Barlas’ anarchic behaviour continued during the hearing at the Police Court, where he refused to stand up in front of the Magistrate and questioned the court on his sub-standard treatment while in custody (he wasn’t allowed to wash that morning or have a ‘better breakfast’). Barlas resisted being removed from a crowded court by the police and used the ‘most violent language, and yelling and kicking’.

Extract from Perth Prison admission register, detailing Barlas’ admission in July 1894 (over two pages). After his appearance at Crieff Police Court, Barlas was imprisoned at Perth Prison on 21st July 1894. This extract from the prison’s admissions register states that Barlas was transferred to Gartnavel Asylum on 31st July 1894.

Crown copyright, NRS, HH21/47/6 page 109.

Barlas’ imprisonment in Perth Prison lasted little more than week, as he was certified insane and transferred to what was then known as Glasgow Royal Lunatic Asylum (later named Gartnavel Royal Hospital). During his time at Gartnavel, his writing flourished and it was his most creative period. Unfortunately the many dramas, novels and essays he wrote in hospital did not survive. Barlas died there in 1914.

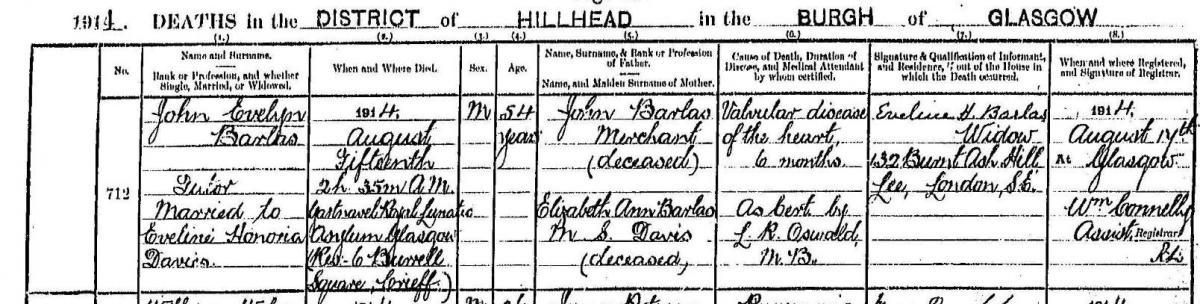

John Evelyn Barlas’ death certificate. Barlas died while hospitalised at a mental health facility, Gartnavel Asylum, since his assault charge in 1894.

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory of Deaths, 1914, 644/12/712 page 238

In this article we have explored the rich and diverse history of Perth Prison, reflecting on its inmates over the centuries. We plan to add more prison registers to Scotland's People over time to give insight into other Scottish prisons and the stories of their prisoners.

Further reading

For more information on searching the prison registers on Scotland's People, and what they contain, see our prison register guide.

You may find the handwriting in the prison records difficult to read. Look at the guide on reading older handwriting, the Scottish Handwriting resource, and search the glossary for assistance with abbreviations, legal terminology, occupations and other unfamiliar words.

Please see our crime and criminals guide for further information about other types of records held at NRS.