Located on Scotland’s west coast about 35 miles from Glasgow, Largs is one of Scotland’s most attractive and popular seaside towns. However, Largs has a darker history, one that we can explore through the newly released records of the town’s prison registers from the period 1843-1853.

Largs, a small coastal town in Ayrshire. Photomechanical print, c. 1890.

Image credit: The Library of Congress, public domain

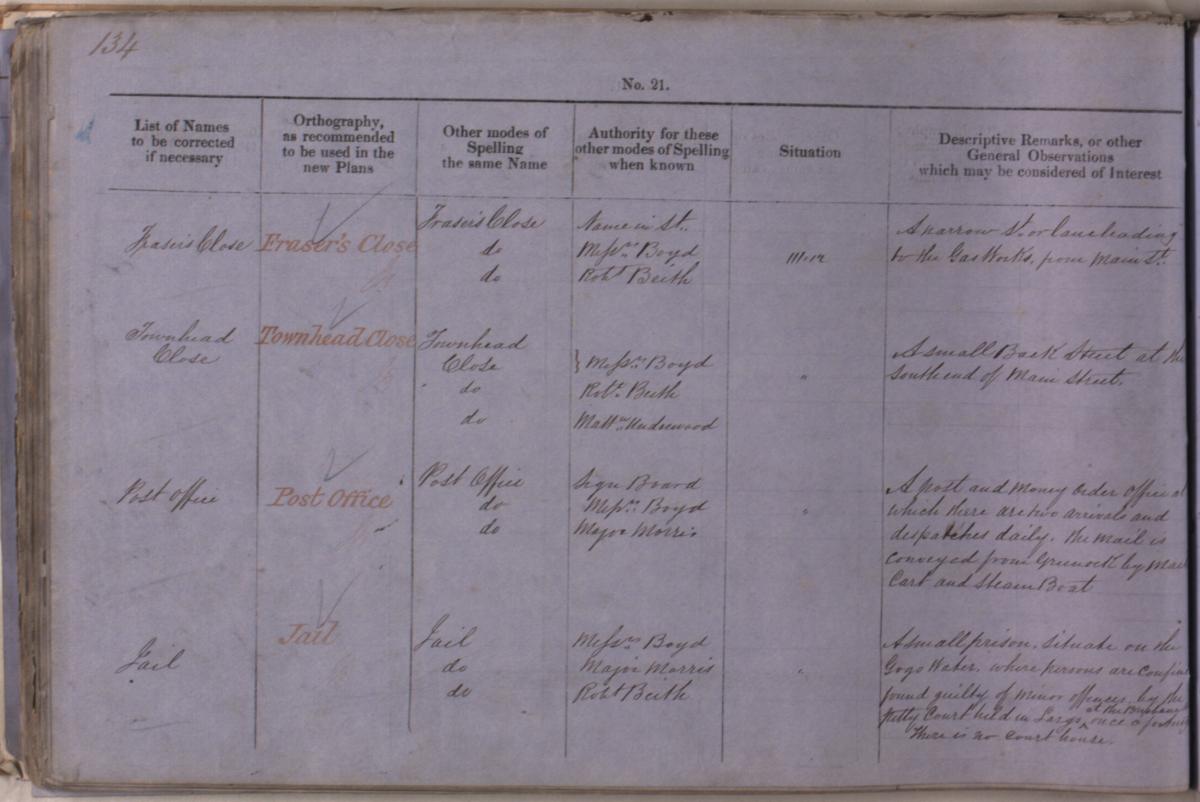

Before it became popular with holidaymakers and day-trippers in the late nineteenth century, Largs was a small village centred around its kirk. The town’s prison was similarly small-scale; in 1817 it consisted of nothing more than a converted two-story dwelling located on Gogo street. Largs also lacked a formal courtroom and court cases were tried before a Justice of the Peace in a room in the Brisbane Hotel. The General Board of Scottish Prisons took over management of the prison in 1842 and preserved the somewhat unusual custody arrangements, as detailed in the 1855-1857 Ordnance Survey Name Book for Ayrshire:

Description of Largs Prison in the Ordnance Survey Name Book for Ayrshire, 1855-1857.

‘A small prison, situate on the Gogo Water, where persons are confined found guilty of minor offences, by the Petty Court held in Largs at the Brisbane Hotel once a fortnight. There is no court house.’

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Ordnance Survey Name Book for Ayrshire, 1855-1857, OS1/3/42 page 134

Prisoners (both female and male) were commonly detained in Largs Prison for one or two nights due to the minor crimes they were convicted of. From studying the admission registers accessible via ScotlandsPeople, we can see these were generally for breach of the peace or for being drunk and disorderly. For those charged with more serious crimes, the accused often spent a night in Largs Prison awaiting their transfer to Ayr High Court or Kilmarnock Sheriff Court to be tried.

We capture a glimpse of the conditions prisoners experienced from the annual prison inspection reports which were established after the Prisons Act, 1835. Largs prison was inspected for the first time on 17th July 1844 and the report noted that it was opened in ‘November last for the reception of prisoners before trial, and of convicted prisoners for periods of not more than ten days’ and that 30 prisoners had been admitted within that period of 8 months. The inspector described that the prison was empty at the time of the report but that prisoners had been admitted without warrants and usually in an intoxicated state.

Also documented were the two rooms for the accommodation of the keeper of the prison, which was inadequate for the ‘keeper and his family’. The keeper was a local weaver, working a loom outwith the prison, keeping him away from his prison duties. The inspector commented that the keeper’s salary of six pounds a year for ‘the small amount of duty which has to be performed’ was insufficient to live on. Interestingly, this report also mentions that the admission registers ‘were in arrears, and had not been neatly kept.’ This somewhat careless approach to recordkeeping can be confirmed by examining the prison entries for 1843-1844, which are written in an erratic hand and are littered with spelling mistakes.

Another inspection report of 8th June 1848 described Largs jail as a ‘small prison of three cells’ and noted that its security arrangements were less than ideal: the ‘boundary wall is only 5 feet high, which presents little obstacle to those outside communicating with prisoners within.’ There was also concern regarding the damp conditions of the cells and the inspector suggested lighting a fire in each cell when it was unoccupied as a possible remedy. The prison was inspected again in 1852, which noted that the prison was in good repair, ‘but the boundary wall is not secure’ and goes on to describe the escape of a prisoner ‘during the absence of the keeper’.

Detail from an Ordnance Survey plan of Largs, showing the location of the 'jail' to the west of Gogo Bridge.

National Records of Scotland, Ordnance Survey 6 inch plan (Ayrshire, sheet III), RHP48760

At the time of the 1848 inspection, there was one female prisoner in custody. By consulting the admission register on ScotlandsPeople we can determine that this woman was ‘Grace Kechnie or Quin’, who appears to be a regular guest at Largs Prison, as she was also admitted in January and March that same year. From the register we can also garner that Grace was charged with being drunk and disorderly and breach of the peace, was Irish and had dark hair, ‘gray eyes’ and was ‘slender made’. She was released on 15th June 1848, perhaps not for the final time.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the ramshackle prison was no longer fit for purpose. Ayr Prison was progressively extended and began to take longer-term prisoners from across the central west coast of Scotland, leading to the eventual closure of small jails in other towns. This process was remarked upon in the minutes of the General Board of Directors of Prisons in Scotland; ‘completion of the new addition to the Prison of Ayr […] recommending the discontinuance of the small Prisons of Largs, Cumnock, Saltcoats, Stewarton, Irvine, Beith and Girvan.’ (Minutes of Committee on Local Prisons, 5 May 1853, NRS, HH6/11).

While the long-term fate of small town prisons like Largs was clear from the 1850s onwards, it is possible that the Largs facility survived for as long as twenty years. The admission registers held by National Records of Scotland (NRS) ceased in 1853, but the ownership of its buildings and land was not transferred from the Prison Board to ‘Thomas Robertson, Metal Refiner’ until 1871. (Particular Register of Sasines for Ayr on 1st May 1872, NRS, RS91/57/183). The date of 1871 is significant as Largs’s first police station opened that year and this new facility allowed those who were awaiting trial to be confined in the station cells. Perhaps the most likely explanation is that from 1853 Largs ceased to accommodate sentenced prisoners, but continued to serve as a custodial suite for those arrested but not yet tried.

The site of the former prison was described in the Inland Revenue Field Books (NRS, IRS55/395, p 765) compiled between 1910-1920 as Victory Place, a tenement being occupied by its owner Malcolm Stevenson and six others. According to the 1921 census enumeration entries, the former prison site had been divided into eight separate homes. The original prison building was demolished and the site at 33 Gogo Street is now occupied by modern purpose built housing.

Detail of the site of Largs prison, plot 765, then known as Victory Place, on the south side of Gogo Street, 1910-1920.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Inland Revenue Survey plan for Ayrshire, 1910-1920, IRS104/18

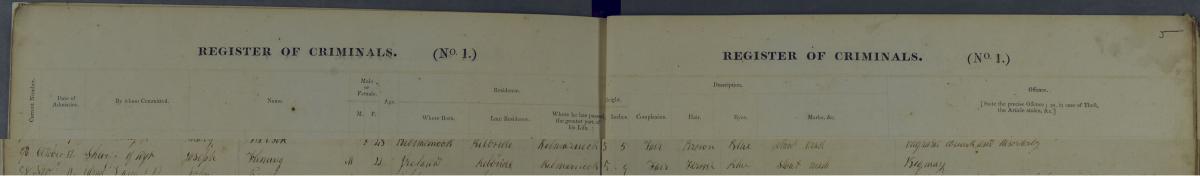

Prisoner profile – Joseph Fleming

Joseph Fleming (entry 90) in the Largs Prison register for 1845. He is recorded as being charged with the offence of 'bigmay' [sic].

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, HH21/38/1 page 5

By examining the Largs prison records in conjunction with other online records held by the NRS, we can build up rich and detailed pictures of the lives of people who were unfortunate enough to find themselves incarcerated there. One such example is the case of Joseph Fleming who was admitted to Largs Prison on 12th October 1845 on a charge of ‘bigmay’ [bigamy].

Fleming was sent to Largs Prison from the Kilbride area and is described by the prison keeper as having ‘fairish’ hair and being clean and sober upon admission. Fleming’s trial took place at Ayr High Court on 25th April 1846 and by consulting the court papers it is possible to discover more about the case. Fleming was married in 1830 to Elizabeth Fair in Kilmarnock, and can be found recorded in the Old Parish Register:

Detail of Fleming and Fair’s marriage entry, 14th June 1830.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Old Parish Register of Marriages for Kilmarnock, 1830, 597/110 page 18

In his Declaration, which forms part of the court process papers, Fleming confirms that he did marry ‘Betty Fair’ in the ‘presence of strangers’ known only to her. One of these witnesses, a James Grant, eloped with Fair ‘about eleven years ago’ and Fleming had heard nothing of his first wife since. Fleming said that he was told by neighbours in Kilmarnock that Fair had ‘got herself intoxicated and fallen into a Loch about Dalkeith and been drowned.’ Fleming married his second wife, Janet Robertson, on 29th December 1838 in West Kilbride. Fleming’s first wife, Elizabeth Fair, appeared as one of the witnesses in the trial and gave her version of events, saying it was in fact Fleming who had deserted her and, having not heard from him for a number of years, had herself gone on to marry a Kenneth Peebles in 1839. Peebles and Fair were married in Haddington, so some distance from her first marriage to Fleming:

Proclamation of banns for Kenneth Peebles and Elizabeth Fair, 15th July 1839.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Old Parish Registers Marriages for Haddington,1839, 709/1 page 154

It has not been possible to find a case of bigamy against Elizabeth Fair or Fleming in the following years. Joseph Fleming, ‘about 43’ years of age according to his Declaration, was sentenced to nine years imprisonment.

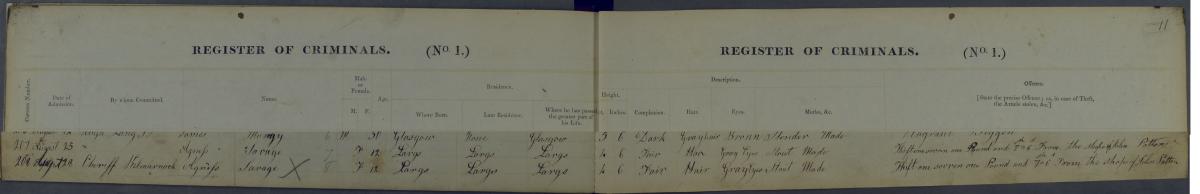

Prisoner Profile – Agnes Savage

Agnes Savage, aged 12, appears in Largs Prison register twice in August 1848 (bottom two rows).

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, HH21/38/1 page 11

Largs prison housed children alongside adult prisoners. We can also see the relatively harsh treatment meted out to young offenders convicted of minor crimes.

Twelve year-old Agnes (recorded as ‘Agness’ in the Largs Prison register) was admitted to Largs Prison on 25th August 1848 and sent to Kilmarnock to be tried. She returned to Largs Prison to fulfil a 20 day sentence. The register records that she was charged with the crime of ‘Thift one souren one Pound and 7 shillings and 6 pence From the shope of John patton [sic]’. The prison keeper found her to be sober with ‘fair hair’ and ‘gray’ eyes and she was ‘Stout made’.

In the 1841 census, Agnes is enumerated aged five, living with her parents on School Street in Largs, a short distance from John Paton’s flesher or butcher’s shop on Gallowgate. There is still a butcher’s shop in Largs today by the name of A.D. Paton, situated on Aitken Street.

It would appear that Agnes’s experience of an adult prison at an early age did not lead to her becoming a career criminal and there are no further mentions of her name in the Largs prison records after her release. Five years after her incarceration, a teenage Agnes Savage of Largs was married to Henry Leighton:

Detail of Agnes Savage and Henry Leighton’s marriage entry, 1853 (Savage was aged about 18).

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Old Parish Registers for Largs, 1853, 570/9/8 page 8

By the 1861 census, the couple were living in the town of Lochwinnoch, 14 miles west of Largs. Henry Leighton is recorded as a vintner originating from Ireland and the couple have two sons, William, aged five and James, aged one.

The Largs Prison registers record ten years of admissions to this small jail at a time of great change for Largs and for Scottish society in general. Those who passed through the ramshackle jail overlooking the Gogo Water undoubtedly had their lives changed by the experience. The information contained within these registers not only gives a clear sense of how justice operated in small towns during the mid-nineteenth century, but also gives us a rare glimpse into the life histories of those confined within.

For more information about prison registers and how to search them, please see our guide on prison registers on ScotlandsPeople.

We have also updated our glossary of abbreviations, words and phrases to include terms found in the prison registers.