More than 2,400 historic maps, plans and drawings from National Records of Scotland (NRS) collections have been made available on the ScotlandsPeople website. Many of the maps show the changing Scottish landscape over time. They also record where people lived or worked, so they can throw light on ancestors’ lives and even suggest new avenues for research. The maps and plans cover certain areas of Scotland, but not the whole of the country. They include both country estates and plans of towns and cities, including for example Glasgow. Most of the maps and plans originate in the records of court cases, Scottish government departments, Heritors’ records, as well as in private collections gifted to or purchased by NRS.

If you would like to find out more, read our maps and plans guide, or search the maps and plans.

The maps and plans collection is amongst the finest in the UK and contains the largest number of Scottish manuscript maps and plans held by any single institution. Spanning four centuries, the collections cover both manuscript and printed topographical maps and plans. They are particularly strong in estate and railway plans; architectural drawings; and engineering drawings, particularly of ships, railway engines and rolling stock. More maps and plans will be added to the ScotlandsPeople website.

A selection of these items is illustrated below:

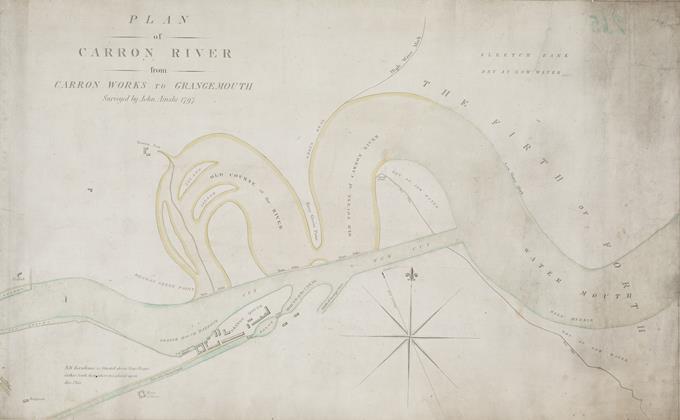

Plan of the Carron River from Carron works to Grangemouth, 1797

National Records of Scotland, RHP242/2

This plan of the Carron River was drawn in 1797 by John Ainslie, one of the foremost mapmakers of his time. His great map of Scotland, drawn between 1787 and 1788, was a landmark in clarifying the outline of Scotland. The River Carron is almost 14 miles in length; rising in the Campsie Fells it is shown here passing what was one of the most important industrial sites in Scotland, the Carron Works which manufactured cast iron goods, and continuing down towards Grangemouth.

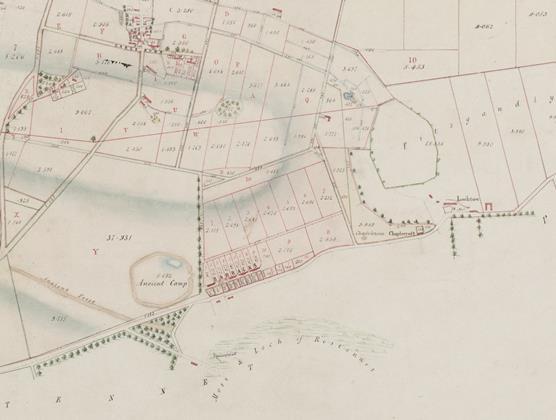

Detail from the plan of the estate of Carse Gray, Angus, 1815

National Records of Scotland, RHP505

This is an example of one of the many estate plans NRS holds: the estate of Carse Gray, just east of Forfar in Angus. Drawn in 1815 by William Blackadder, it depicts the property of Charles Gray. A table provides information about the use of areas of land on each farm, and details how the ground is divided (arable or pasture farming), and whether there are gardens or woods. In 1815 there were many more houses at Carseburn at the top of the map than exist nowadays. The bottom of the plan records an archaeological feature marked as an ‘ancient camp’, beside the settlement now known as Lunanhead.

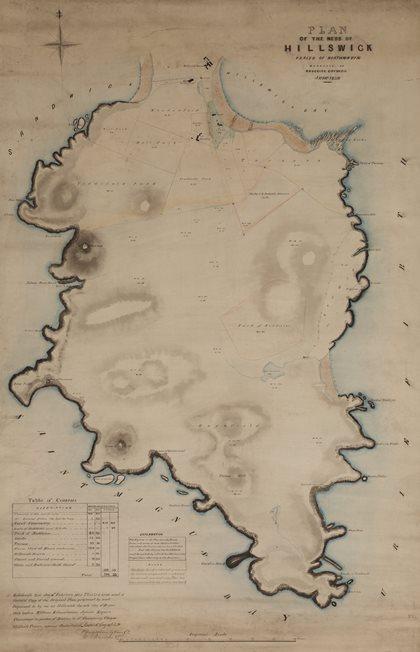

Plan of the Ness of Hillswick, Northmavine, Shetland, 1859

National Records of Scotland, RHP532

Some plans include details of commonties. These were areas of land held in common by several proprietors, on which tenants might be allowed to pasture their livestock. Roderick Coyne, a civil engineer, recorded the commonties at The Ness of Hillswick in Northmavine, Shetland, in 1859. Modernising landowners were keen to have commonties divided so they could try out new methods of farming or consolidate their stock. When applications were made to the Court of Session to divide the land, landowners who claimed a share of the land had to submit their title deeds to the court. The land was then shared out depending on the valued rent of the owner’s property. This plan is associated with such a Court of Session case.

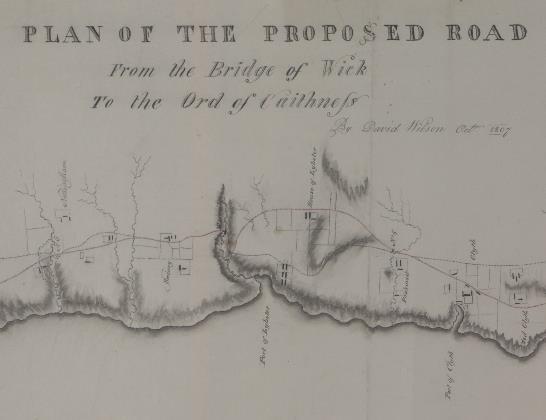

Detail from a plan of a proposed road from the Bridge of Wick to the Ord of Caithness, 1807

National Records of Scotland, RHP11654

Plan of proposed road from the Bridge of Wick to the Ord of Caithness, Latheron, Caithness, 1807, by David Wilson. This detail shows Lybster, the coastal village developed from 1802 onwards by the Sinclair family. Lybster grew to become the third largest herring port after Wick, the northernmost point shown on this map, and Fraserburgh in Aberdeenshire. Thomas Telford supervised the building of the new ‘parliamentary’ road, starting in 1810 at the Ord, the county boundary with Sutherland, and reaching Wick in 1812-3.

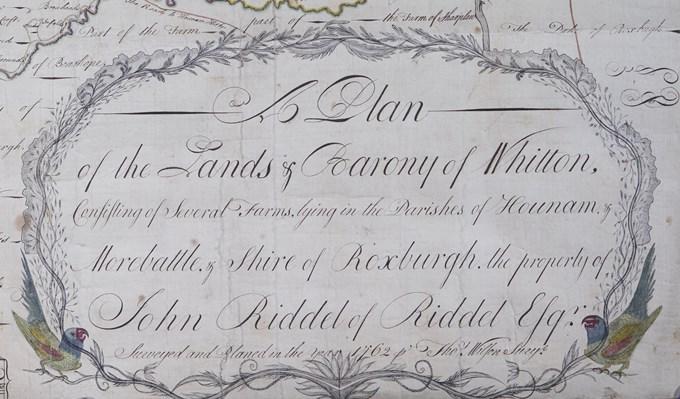

Detail from a plan of the barony of Whitton, 1762

National Records of Scotland, RHP32927

Maps and plans are not just utilitarian objects, but can also be decorative and artistic, demonstrating the taste and fashion of a period. This estate plan of the barony of Whitton in Roxburghshire, drawn by Thomas Wilson in 1762, shows farms, houses, roads, burns and other landscape features. The title is illustrated with a decorative cartouche flanked by two parakeets and surrounded by a leaf, vine and floral border.

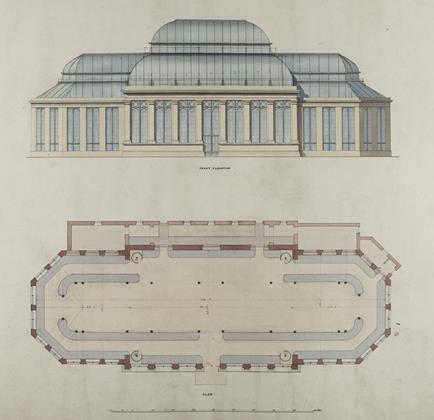

New Palm House, Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh: front elevation and plan, 1854

National Records of Scotland, RHP6521/19

The maps and plans added to ScotlandsPeople include architectural drawings as well as topographical material. This architectural drawing is of the New Palm House at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh and dates from 1854. The New Palm House was designed by Robert Matheson, architect for Scotland for HM Office Works – this drawing shows the front elevation. It is still in use and is one of the main features of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Edinburgh. Matheson also designed New Register House and the rotunda at the back of General Register House, Edinburgh, named the Matheson Dome in his honour. They are occupied by National Records of Scotland.

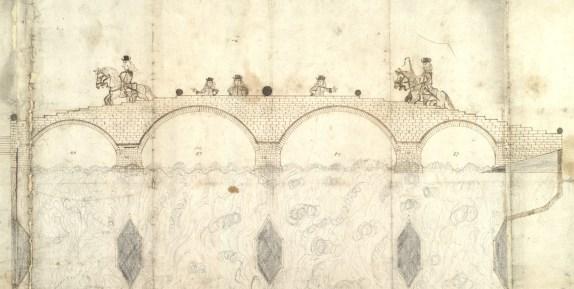

Drawing of a bridge intended to be built at Dumbarton, 1684

National Records of Scotland, RHP3493

Some drawings even include illustrations of people. This example dates from 1684 when it had become clear that a bridge was needed for the safe passage of cattle being herded from the Highlands to the Lowlands across the River Leven at Dumbarton. A bridge would remove the need for a 24 mile detour to the bridge over the Forth when bad weather made it unsafe to cross through the water. Stones were already being quarried by 1683, but work did not begin until 1754, prompted by fears that Dumbarton would be isolated when another bridge was built further up the river. The Dumbarton bridge wasn’t completed until 1765.