‘The scene which but a few minutes before was one of joyous excitement was suddenly changed, and all who had friends or relatives near to the place were in a state of the greatest anxiety or distress, inquiring for their safety…’ (Weekly Chronicle (London) Saturday 10th September 1842).

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert made their first visit to Edinburgh in September 1842, four years after the Queen’s coronation at Westminster Abbey on 28th June 1838. The visit and tour were originally intended to be a private event. It was soon recognised, however, that, as only the second visit to Scotland by a reigning monarch since the 17th century, there would be great public interest in the Queen’s movements and a desire to witness her progress through the country. A more public tour was curated to strengthen relations with the Queen’s subjects north of the border. As Alex Tyrrell reflects, there was “great importance to this royal visit. In political, religious, social and cultural matters it was mingled with the ‘main events and more striking traits of the national history.’” (The Scottish Historical Review, volume 821, no. 213, April 2003, page 73)

Indeed, the visit was highly anticipated by residents of the city as well as those based outside the capital. Many banks, businesses and establishments closed in order to allow as many people as possible to be afforded an opportunity to see the royal party. Thousands travelled for miles via canals, steamers, coaches, on foot and locomotive. The Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway companies announced extra trains to run on the days leading up to the visit ‘but such was the anxiety of the people to hasten to the east that on Tuesday forenoon the station was besieged by anxious crowds desirous of procuring places [on the trains].’ (The Dublin Monitor, 5th September 1842).

The newspaper also reported that ‘On Wednesday [the day before Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s arrival in Leith] the aspect of Edinburgh was wholly changed. From having the appearance of a quiet and aristocratic and lawyer-lounging place, it became a scene of bustle, business and animation…along the whole lines of streets, marked out as the royal route, scaffoldings were in course of erection for the accommodation of the people.’

The couple had arrived at Leith on 1st September, greeted by dignitaries including Sir Robert Peel (the Prime Minister) and the Duke of Buccleuch. The Queen noted in her diary ‘The impression Edinburgh has made upon us is very great; it is quite beautiful, totally unlike anything else I have seen; and what is even more, Albert, who has seen so much, says it is unlike anything he ever saw…’(Leaves from the Journal of our Lives in the Highlands, 1848-61, Edinburgh, 1868)

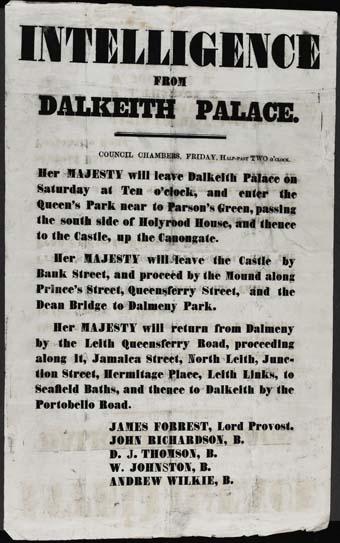

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert stayed at Dalkeith Palace, a residence of the Duke of Buccleuch, having been unable to take up residence at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh due to an outbreak of scarlet fever.

A photograph of Dalkeith Palace taken in 1865.

Credit: Buccleuch Archives/By kind permission of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, KT

They left Dalkeith on the morning of Saturday 3rd September in an open carriage drawn by four bay horses, escorted by a detachment of the Enniskillen Dragoons. Walter Scott’s romanticised version of Scotland may have influenced the attire of the royal couple: The Queen wore a silk dress of Royal Stuart tartan and a blue shawl and was accompanied by Prince Albert who wore the green ribbon and jewel of the Order of the Thistle. Multiple carriages followed, those amongst them included the Duchess of Buccleuch and the Duchess of Norfolk.

A poster outlining the journey to be made by the Queen from Dalkeith Palace.

Credit: Buccleuch Archives/By kind permission of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, KT , National Records of Scotland (NRS), GD224/524/2/7/5

Upon their arrival in Edinburgh, the Queen and Prince Consort were met with dense crowds: ‘every window was filled, and a great many balconies had been erected along the fronts of the houses which were tightly packed with delighted gazers…every ledge and house-top whence a view of the procession could be obtained, was crowded.’ (The Chester Chronicle, Friday 9 September 1842).

The Queen passed by The Palace of Holyroodhouse, acknowledging the crowds, before travelling up the Royal Mile. At Edinburgh Castle she examined the siege gun, Mons Meg, and took in the view across the city. The crowds swelled, eager to see Her Majesty, and followed the royal party down the Mound as it progressed onto the main thoroughfare of Princes Street.

At the foot of the Mound was scaffolding which had been erected to give onlookers a better vantage point; with the excitement and rush of the crowd, too many people had climbed and clung on to the platform and it ‘gave way, and precipitated several hundred people to the ground.’ (The Chester Chronicle, Friday 9 September 1842)

The Queen had not witnessed this event, which occurred only just after her cortege had passed through to the west of the city. Upon her arrival at Dalkeith Palace later that day she was told the news and was ‘much affected by the recital, and immediately dispatched a special messenger to Edinburgh, to collect all the information possible upon the subject.’ (Weekly Chronicle (London) Saturday 10 September 1842).

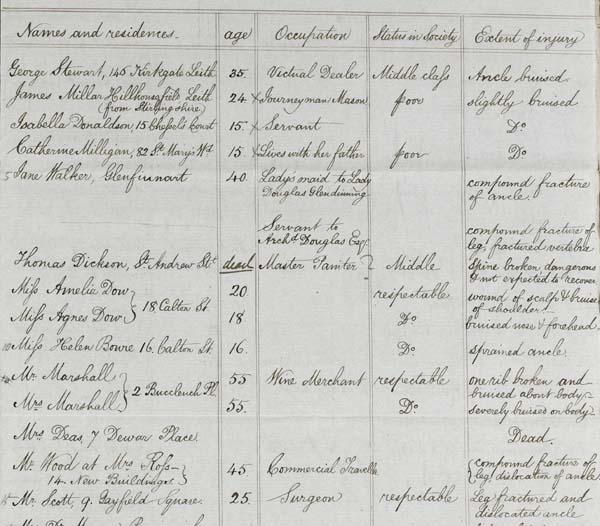

With immediate effect, the Duke of Buccleuch tried to ascertain the cause of the accident and how badly members of the public had been injured. By that evening he had received a letter from a J Gibson with initial findings from his investigations:

“My Lord Duke,

I have been to the Council Chamber, the Sheriff Officer and the Police Office. The result of my enquiries is that no one was killed on the spot, - that about 25 were more or less injured by the falling of the scaffold at the end of the Mound. There is no authentic account of any having since died, but I have [heard]… the same report that one, - a Mrs Deas has died that I fear this is true. She was pregnant.” (Buccleuch Archives/By kind permission of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, KT, NRS, GD224/524/2/7/12)

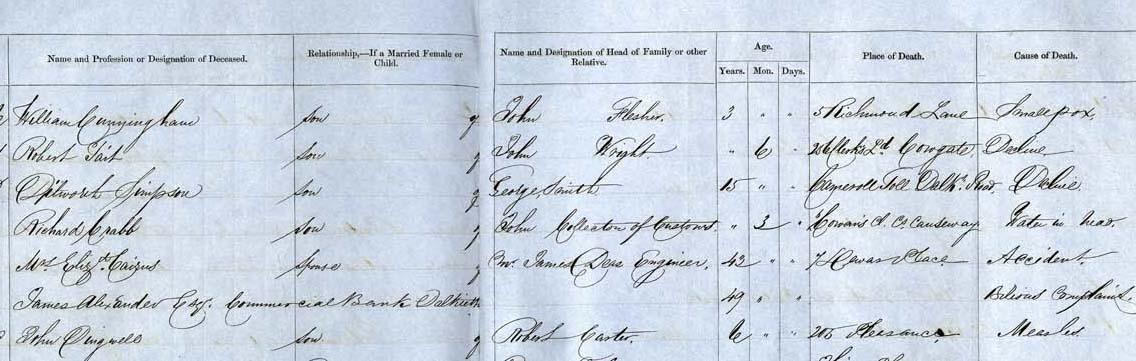

Accompanied by the letter was a list of those injured with their name, age, occupation and class. This was later replaced by a more accurate version following further inquiries:

A list of people injured and killed during the accident

Credit: Buccleuch Archives/By kind permission of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, KT, NRS, GD224/524/2/7/15

James Buist, in his 1842 publication ‘National record of the visit of Queen Victoria to Scotland’, described the scene: ‘The casualties included about fifty persons, chiefly of the superior classes of society, the injuries consisting principally of broken legs; one lady, in particular, had both legs broken. Several individuals were much injured about the head and chest; and several dislocated arms were immediately reduced on the ground. A subscription was opened afterwards for behoof of the poorer sufferers by this distressing accident, to which her Majesty, with her accustomed kindness and munificence, contributed one hundred pounds.’ (page 53).

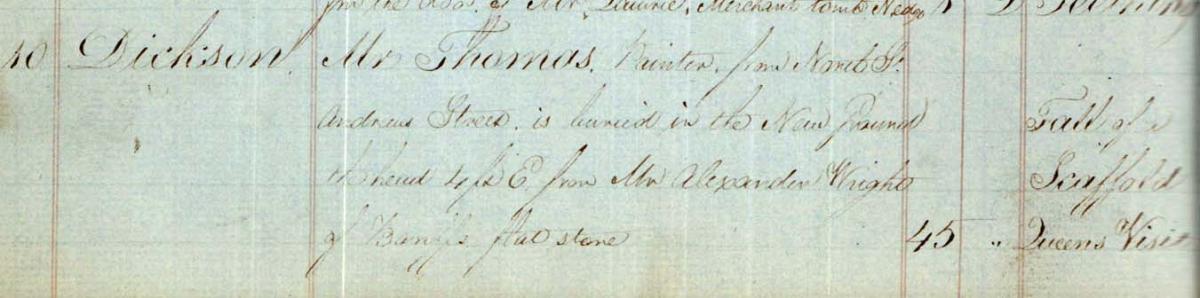

A letter written on the night on the 3rd of September 1842 to the Duke of Buccleuch describes that the injuries to one of the spectators was ‘likely to be fatal – the case of a painter of the name Dickson from injury of the spine.’ (Buccleuch Archives/By kind permission of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, KT, NRS, GD224/524/2/7/14)

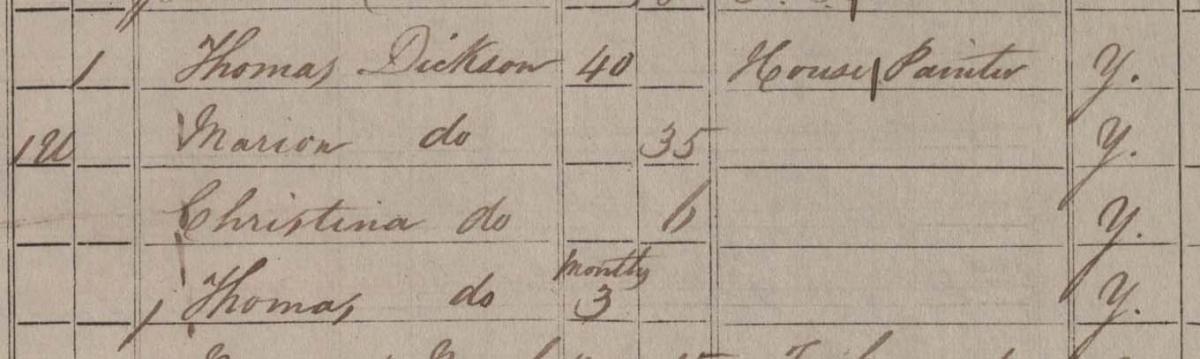

Thomas Dickson was a house painter, around 45 years old, who lived with his wife Marion, his seven-year-old daughter Christina and one-year-old son Thomas at 10 North St Andrew Street, Edinburgh. Thomas and Marion had married in February 1834, a short time before their daughter was born.

The Dickson family enumerated in the 1841 census

Crown copyright, NRS, 1841 census, 685/1 6 page 1

Thomas was seriously injured in the accident – the Weekly Chronicle (London) reported that he was in a bad condition with ‘compound fracture of the leg, fractured vertebrae, spine broken, dangerous, not expected to live.’

He died four days later ‘after severe suffering’ (Liverpool Standard and General Commercial Advertiser, Tuesday 13th September 1842).

The Old Parish Register of Deaths for Leith South records that Thomas Dickson ‘Painter from North St Andrew Street, is buried in the New Ground’ of Calton Burying Grounds. His cause of death was ‘Fall of a Scaffold at Queen’s Visit.’

Thomas Dickson’s death entry

Crown copyright, NRS, Old Parish Register of Deaths for Leith South, 692/2 page 235.

Dickson’s wife, Marion, lived for another two decades, dying in April 1863 from heart disease.

Gibson’s correspondence with the Duke of Buccleuch established that as many as 60 people had been injured and confirmed that Mrs Deas, who he mentioned in his earlier letter, had been a victim of the accident.

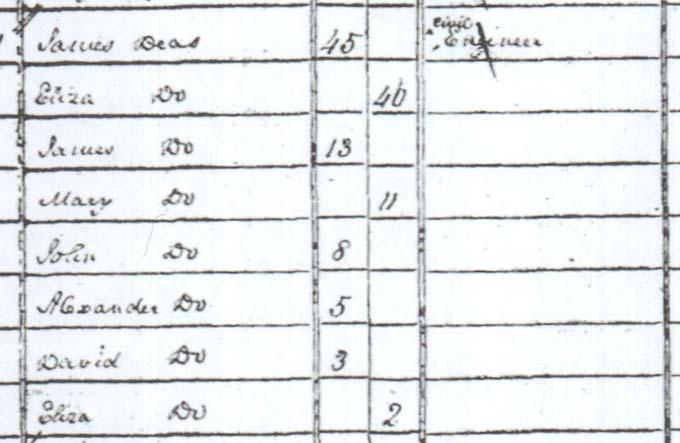

Elizabeth Cairns or Deas lived at 7 Dewar’s Place, Edinburgh, and was the wife of James Deas, a civil engineer. The couple had six children; four boys and two girls.

The 1841 census enumerating the Deas family.

Crown copyright, NRS, 1841 census, 685/2 97 page 9

Whilst almost all injuries were bruising or fractures of limbs, Elizabeth appears to have been one of the very few who died from the collapse of the scaffolding. The Old Parish Register of Deaths for St Cuthberts records her cause of death as ‘Accident’.

The death entry of Elizabeth Cairns or Deas

Crown copyright, NRS, Old Parish Register of Deaths for St Cuthbert’s, 685/2 page 167.

Elizabeth’s eldest son, James, was 14 years old when his mother died. Apprenticed to civil engineer John Miller, he became a successful engineer in his own right. Through his work he transformed the River Clyde in Glasgow and helped to open the city to the trade routes of the world. He became the chief engineer to the Clyde Navigational Trust in 1869, developing the Clyde and its docks.

Further details of the tour of Scotland were captured by the Queen herself in her diary which can be explored online.