On 6th August 1902, in the house at 11 Rochester Terrace, Edinburgh, Colin Sinclair Murray Brown assaulted and killed his landlady, Mary McIntosh. Brown’s case was heard in the High Court of Justiciary, and, having been found insane, he was sent to Perth (General) Prison Criminal Lunatic Department (CLD). Brown is one of hundreds of prisoner-patients featured in a new online release of records for Perth (General) Prison. We explore his story below.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland (NRS), HH17/14

Topics, words and language featured

This article features information and images from the Perth Prison CLD Case Books. These records, from the Victorian era, relate to the admission, treatment and release of prisoners with mental health issues in the 19th century. Terms and language from this historical context are present. As such there are several references to historical medical terms that are no longer medically accurate or acceptable. These include: lunatic, mad, imbecile and insane. There are also descriptions of violence.

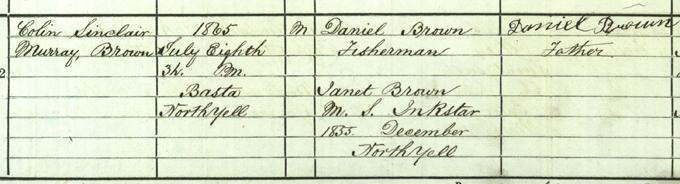

Brown was born on 8th July 1865 on Basta on the island of Yell in the Shetland Islands of Scotland.

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Births, 1865, 004/2 12 page 4

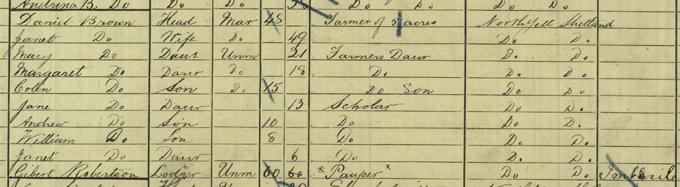

His parents, Daniel Brown and Janet Inkster had married in December 1855. Brown was the third of their children; in total they had nine children, four girls and five boys.

Crown copyright, NRS, 1881 Census, 004/2 1/6 page 6

According to Brown’s brother-in-law Magnus David Thomson, Brown had always had a gentle and retiring temperament. As a young man Brown was supported financially by a local Free Church minister who helped him gain entry to the Anderson Educational Institute at Lerwick (now known as Anderson High School). He then undertook further studies in Aberdeen before, finally, he attended the University of Edinburgh (NRS, HH17/14). Brown’s family were unable to support him financially in his studies. However, he was awarded a bursary and earned additional income through tutoring to enable him to pay his fees.

Brown moved into the McIntosh household at the end of 1901. He was undertaking his divinity course at Free Church College in Edinburgh (today known as Edinburgh Theological Seminary) and was a probationer. Brown required a place to stay whilst in the city and, as part of her evidence, Grace McIntosh, the deceased’s daughter, explained how Brown ‘had asked for rooms and as he professed to be a clergyman we thought he would be a suitable boarder and my mother agreed to let him have a parlour and bedroom.’ (NRS, AD15/02/21).

In the summer of 1902 Brown returned north for three weeks. Grace McIntosh reflected that Brown did not say where he was going when he left, but ‘had always been in the habit of going away at the weekends as we understood to preach.’ (NRS, AD15/02/21) On this occasion he had been in Stornoway and, according to The Inverness Courier (8th August 1902), he was ‘said to have been popular with congregations to which he preached… [and] had filled the pulpit at Stornoway for 3 Sundays previously [before returning to Edinburgh].

Since returning to Rochester Terrace, Brown’s behaviour had changed. Although, as Grace McIntosh commented, he had a ‘peculiar manner’ and often abruptly stopped people speaking by suddenly saying ‘I want no more of that,’ he was generally quiet and respectable. He began to hide in his room, emerging infrequently and on one occasion to ask his landlady to remove all knives from the place, but with no explanation why.

On 6th August Brown became distressed, shouting and roaring in his room all day, alerting neighbours as well as the household. He believed himself to be the king and, despite efforts from Mrs McIntosh, he could not be calmed.

Over the course of the afternoon Dr Thin visited to speak with him. In a later statement, Dr Thin recorded the scene:

“Brown who remained lying quiet on the sofa said he was glad to see me as he had not been feeling well… [He said] that he had been worried and had been working (reading) very hard for his B.D [Bachelor of Divinity] examination and preaching on Sundays. He…felt as if his head were going to turn and sometimes he had an impulse to shout out which he said relieved him. I inquired if he had any impulse to injure either himself or anyone else in the house and he said “God knows I have no impulse of that kind.’ I asked why he had given his bank book and razor to Mrs M[cIntosh] and he said he did so because he felt his brain might give way under the strain of his work and he thought they were better in her keeping… Brown agreed with me that it was a rest from his work that he required. He was quite coherent during his talk with me and was in no way excited and there was nothing in his appearance to indicate that he was insane or dangerous. He spoke quietly all the time and sensibly and my opinion of him was that he was suffering from nervous prostration due to over study, a common enough experience in practise…” (NRS, AD15/02/21)

Dr Thin promised he would send Brown’s brother-in-law, Mr Thomson, a butter merchant, to visit him, but he did not appear that afternoon. Around 9pm Brown was found ‘howling in the lobby near the kitchen door.’ Mrs McIntosh tried to quieten him when Grace heard ‘the noise of a scuffle [and] I went into the lobby and saw my mother lying on the floor of the accused’s room. Accused who was undressed and had on boots was stamping upon her with his feet. My mother was lying motionless.’

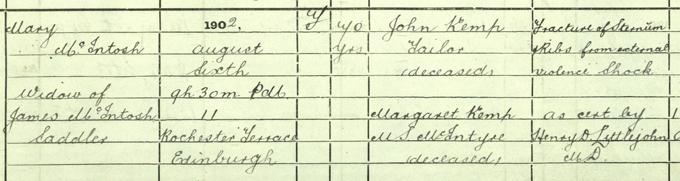

The post-mortem, undertaken by Drs Thin and Littlejohn, provided additional evidence to support the court indictment against Brown that he ‘did beat [Mary McIntosh] with your fists, knock her down and jump upon her and did murder her.’ (NRS, JC26/1902/104)

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Deaths, 1902, 685/5 873 page 291

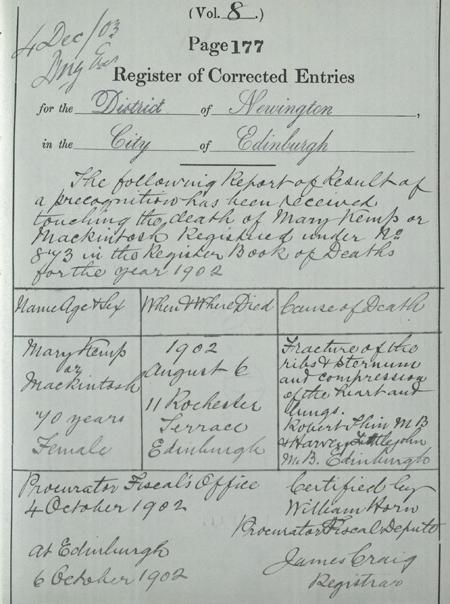

Due to the violent nature of Mrs McIntosh’s death, the Crown Office undertook further investigations to determine the exact cause, which are noted in the Register of Corrected Entries:

Crown copyright, NRS, Register of Corrected Entries, 685/5 8 page 177

Immediately after Mrs McIntosh was murdered, Dr Thin examined the crime scene. He found Brown in his room and, although in an ‘excited state’ he understood what the doctor was saying. Brown said that he dreamt his landlady had ‘come in, lit the gas, came to his bedside and that he dreamt she was going to give him something and that he would not take it and struck her on the face and knocked her down and trampled on her.’ The doctor noted that due to his behaviour and appearance it was clear that Brown was ‘insane’ and his actions were ‘a sudden momentary impulse which led Brown to attack Mrs McIntosh and that at the time he was quite irresponsible for what he did.’ (NRS, AD15/02/21).

James Scott, a Constable with the Edinburgh City Police, conveyed Brown to the High Street Police Office in a cab. Although he did not speak about the incident, he ‘had a wild appearance and constantly kept turning his head from side to side…The only remark he made… was to inquire whether we had far to go… In the Police Office he was told that he had been brought there because he killed his landlady… He began shouting at the pitch of his voice calling upon his Maker and talking incoherently. He repeatedly used the words ‘a dream a dream’… He seemed to me to be completely out of his mind.’ (NRS, AD15/02/21)

On 7th August Brown appeared in court. William Russell, a Constable in the Midlothian Constabulary, sat beside Brown in the Officers Room when the accused ‘suddenly jumped to his feet and began shouting and gesticulating… [saying] something about a soldier and a little boy and he called upon someone to protect him and not let him be taken away.’ Russell and a fellow Constable tried to restrain Brown which resulted in Brown striking Russell on the forehead with his fist. Brown quietened after a few minutes and said, ‘he felt the fit of frenzy coming on him and that he could not keep acting as he did.’ (NRS, AD15/02/21)

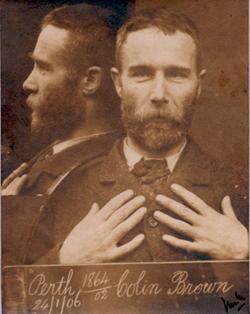

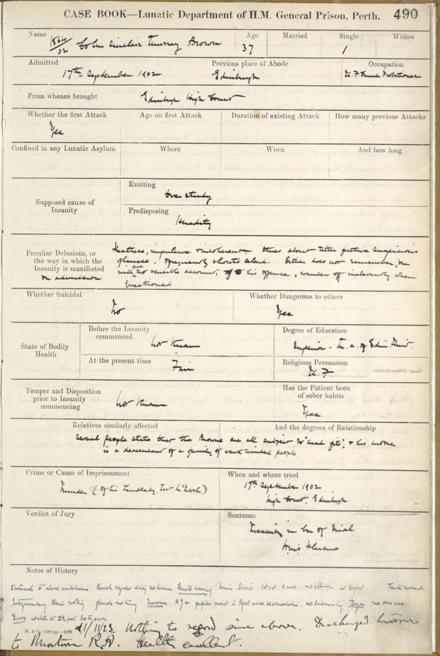

NRS, HH17/14

The Evening Dispatch reported that Brown appeared in court at 12.30, walking unaided. The accused was described in the report as being a ‘well-built man of commanding and ministerial appearance, with a wealth of wavy black hair. He was unkempt and wore a wearied look.’ Dr Littlejohn provided evidence that Brown was ‘a lunatic in a state inferring danger to the lieges.’

Brown appeared again in court on 17th September 1902. Thomson’s Weekly News on 13th September 1902 reported that Brown was led in to a very crowded court room handcuffed to two warders and guarded by two constables. He appeared to be weakened and had grown a beard since his previous appearance. After the Court Officer had intimated who he was to the Sheriff, Brown caused some sensation by shouting ‘I do not know the judge on the bench but he has a wig on.’

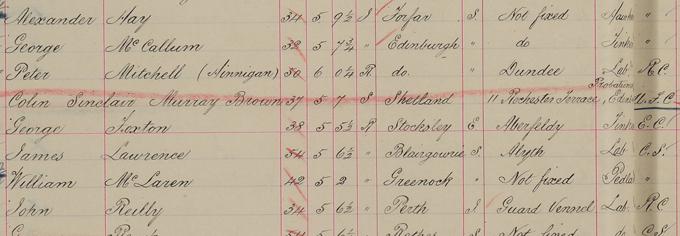

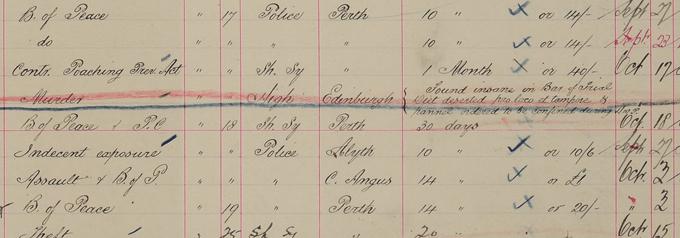

Mr P. Maclagan Morrison, representing Brown, appealed that Brown was insane, both at the time of the alleged offence and at the present time. Due to Brown’s incapacity to be fully tried, he was sent to the Criminal Lunatic Department at Perth (General) Prison immediately after his appearance in court.

Crown copyright, NRS, HH21/47/10 page 7

Brown’s parents appealed to the Superintendent at Perth on various occasions for their son to be allowed to return to their croft on Yell. They wrote to Brown’s brother-in-law, Magnus David Thomson who on, 30th January 1904, conveyed their desire to have their son released on the belief that he was well. Thomson, however, was concerned by this: ‘I cannot say I am of the same opinion as to his mental health judging from the last letter I had from him (Dec 15th).’ Two years later, on 12th October 1906 their local doctor, Henry P Taylor, wrote on their behalf to ask ‘if there is any chance of his liberation, either now or in the future? His parents are anxious to know how he is, and if it would be permissible for him to be released so that they could keep him at his own house. I think they wanted to be satisfied to know exactly what his prospects are, if he is to be a prisoner for life or is there any remote chance of his permanent release at any future time?’ (NRS, HH17/14).

Although no reply to these letters have been noted in Brown’s file, it is evident from other papers and archival records that he was not released. His case was, however, reviewed from time to time.

NRS, HH21/48/3 page 490

Eight years later, in June 1910, the Head Superintendent of the Criminal Lunatic Department in HM Prison Perth wrote to The Commissioners to report on Brown’s conduct since his arrival:

‘For a period of two years after admission…he remained in a condition of confusion and excitement with tricky and troublesome conduct, though employed as a rule at useful work. His condition improved slowly to the extent that he became more settled in conduct, more coherent in talk and free from impulses or noisy conduct. During the past twelve months particularly, he has undergone marked deterioration. A year ago, he was interested in his old studies and though facile and somewhat irrelevant there was still the intellectual interest maintained. He now works in the garden and spends his time generally like an automaton. He has no initiative…He takes no interest in his former studies reads none and talks quite childishly when an attempt is made to interest him in a conversation that extends beyond dates and commonplace facts. He is in fact becoming demented and in my opinion is quite a fit subject for treatment in an ordinary asylum.’ (NRS, HH17/14).

This report followed a review of Brown’s behaviour taken a few weeks earlier on 18th May which recorded that he ‘is now the subject of dementia of the second degree, and it will not be long before it passes into that of the third degree… He has given up all reading and writing, prefers to walk about speaking to himself, and holding up his hands to the sky. He has exhibited no dangerous symptoms for many years. He is a kindly and peaceable man and said to be much respected by the warders and fellow-inmates.’ (NRS, HH17/14)

On 30th July 1910, Colin Sinclair Murray Brown was transferred to Montrose Royal Asylum on a warrant by the Secretary for Scotland.

A criminal lunatic file held in National Records of Scotland, reference HH17/14, includes a letter from Brown himself, written on 22nd October 1919 from Montrose. In the letter Brown asks for his possessions, believed to have been sent to Perth on his admittance there. His belongings were recorded as a ‘watch and chain, ring, papers, cash £4 8 [shillings] 1 ½ pence.’ Brown was anxious that these items be sent to Montrose Royal Asylum. A note added to the bottom of the letter states that on his admittance in 1902 he had no money on his person. It is not clear from the file whether he received his belongings.

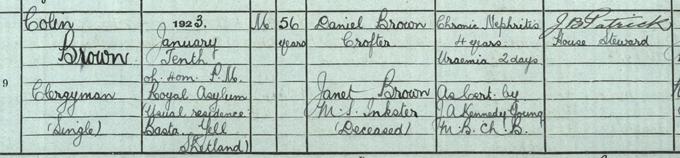

Brown died on 10th January 1923 in the Royal Asylum, Montrose, aged 56. His cause of death is recorded as chronic nephritis (inflammation of the kidneys). One of the house stewards working in the asylum signed the certificate.

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Deaths, 1923, 312/9 page 9

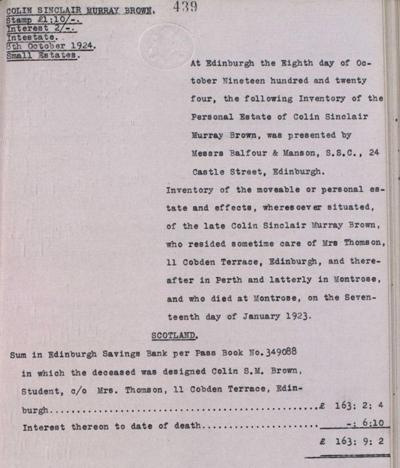

Despite having been in the asylum for 21 years, Brown had left an estate totalling £163, 9 shillings and 2 pence with the Edinburgh Savings Bank. This was the equivalent to around £4,750 today according to The National Archives’ currency converter. His sister, Jane, was the executrix of his estate.

Crown copyright, NRS, Wills and Testaments, SC70/1/719 page 439

A free resource is available to access on the National Records of Scotland’s website which explores the records of people committed to the Criminal Lunatic Department in Perth: ‘Prisoners or Patients? Criminal Insanity in Victorian Scotland.’ Created as part of an exhibition of the same name, the exhibition focused on the records amassed in the prosecution and treatments of those classed as ‘prisoner-patients’, examining details of the crimes through the prisoner-patients’ own words, and the notes of doctors and prison officials as they attempted to help these men and women.

Colin Brown’s case notes are now available to search in the Prison registers category on Scotland’s People.