Scotland's People gives access to the official records of some of the most important events of our lives. Recorded in the Registers of Vital Events, every January we release the records of people who were born 100 years ago, married 75 years ago or died 50 years ago in Scotland.

The entries of the people who died in Scotland in 1973 are now available to search and save on the Scotland's People website. They are part of over 250,000 images released in January 2024 which include birth entries in 1923 and marriage entries in 1948.

The total number of deaths registered in Scotland in 1973 was 64,545, of which 32,954 were male and 31,591 female. This was a decrease of 472 from the previous year’s total of 65,017.

The father of radar

One of the men who died in 1973 was Sir Robert Alexander Watson-Watt, known as the ‘father of radar’. His scientific developments greatly contributed to Britain’s victory in World War Two.

Sir Robert Alexander Watson-Watt

Credit: Public domain image from Wikimedia

Robert Alexander Watson-Watt was born on 13th April 1892 at 5 Union Street, Brechin, Forfar, the fifth son and youngest child to Patrick and Mary.

Detail from the birth entry of Robert Alexander Watson-Watt

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland (NRS), Statutory Register of Births, 1892, 275/86 page 29.

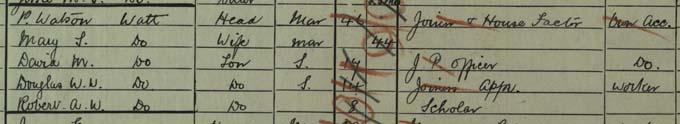

As a young boy, Watson-Watt attended Damacre Primary School; he is enumerated in the 1901 census as an eight year old ‘scholar' living with members of his family at 5 Union Street.

The Watson-Watt household in the 1901 census.

Crown copyright, NRS, 1901 census, 275/2 page 2.

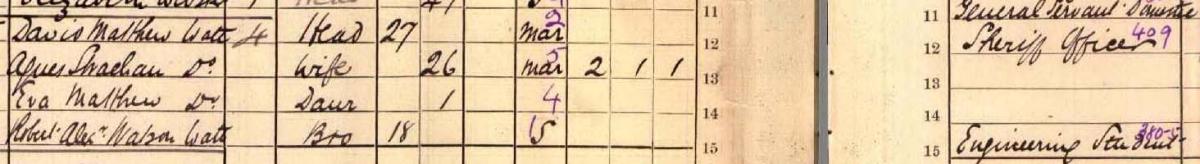

He continued into further education after being awarded two bursaries, one to attend Brechin High School and another to study at University College, Dundee, then a part of the University of St Andrews. The 1911 census enumerated him as an 18 year old engineering student living with his brother, David, his sister-in-law Agnes and their one year old daughter Eva at the family home in Brechin.

The Watson-Watt household in the 1911 census.

Crown copyright, NRS, 1911 census, 275/2 page 1.

The following year, Watson-Watt graduated BSc (engineering) having won medals for his studies including the Carnelley Prize for Chemistry and a class medal for Ordinary Natural Philosophy. Professor William Peddie offered Watson-Watt an assistantship and encouraged him to study ‘wireless telegraphy’ (the common name for radio at the time), educating him on the physics of radio frequency oscillators and wave propagation.

The Scotsman reported that ‘as a boy [Watson-Watt] had been fond of devising all kinds of gadgets for the house, but his particular interest was meteorology, and when war had broken out he found work in the Meteorological Office.’ (7th December 1973).

During the war, on 20th July 1916, Watson-Watt married Margaret Robertson in Hammersmith, London, England. Their marriage ended in divorce in October 1952; the following month he married Jean Drew Smith, a Canadian. They were married at Caxton Hall, London, on 20th November 1952 in an intimate ceremony only attended by Sir Robert’s nephew and a few personal friends. Jean died in 1964 at Sterling Forest, New York.

During his time in the Meteorological Office, Watson-Watt experimented with systems to determine the optimal methods for the early detection of lightning in order to give airmen advanced warning of potentially dangerous flying conditions. In 1924 he began work at a new research centre in Ditton Park near Slough, England, and subsequently led the Radio Department in Teddington, Middlesex, England. There he spent time investigating radio interference and the ways in which it could be used in times of warfare.

The British Government had originally asked Watson-Watt to invent a ‘death ray’ whereby radio waves would heat up enemy aircraft and trigger their explosives to detonate. It was quickly determined that this wouldn’t be possible. In 1935, however, Watson-Watt wrote a memorandum to the Government explaining the ways in which radio waves could be used to detect aircraft; by July of that year he proved through experiment that he could locate aircraft consistently from a distance of around 90 miles away.

Despite some initial doubt amongst colleagues about the practicability of the new method of detection, Watson-Watt was able to develop his ideas in the greatest secrecy with a £10,000 grant. He continued to lead the development of radar detection which became Britain’s secret weapon in beating the Luftwaffe during World War Two as his inventions gave the Royal Air Force advanced warning of German aerial attacks. The Luftwaffe outnumbered the British aerial forces 3-1 at the Battle of Britain in 1940, however this advanced warning, known as ‘Chain Home’, allowed defensive planes to be scrambled and intercept the enemy even through thick layers of cloud. This method was also used in the efforts to sink enemy U-boats.

This success had come at a steep economic cost – on 27th March 1946 the Daily News (London) reported that the development of radar had cost the allied sides considerably more than the £500,000,000 which was spent on the atomic bomb. The newspaper reported that Watson-Watt had disclosed at the Radiolocation Convention that expenditure was around £1,000,000,000 during the six war years. “Approximately half of this, and a much bigger percentage of the expenditure on radio immediately before the war, was on radiolocation” he had explained.

Watson-Watt was knighted for his war work in 1942 and received other honours including the U.S Medal of Merit.

An example of the Medal for Merit. This medal was awarded to Methodist Missionary Reverend Archie Wharton Ellesmere Silvester for hiding 165 survivors of USS Helena for 8 days on Vella Lavella in the Solomon Islands in World War Two.

Credit: Collection of Auckland War Memorial Museum Tamaki Paenga Hira, 2005.56.1

In 1952 Watson-Watt was awarded a tax-free prize of £50,000 ‘in respect of his initiation of radar and his contribution to the development of radar installations’ by the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors. This was the top prize from a total of £94,600 that the Royal Commission granted to 24 scientists that year; his award was the highest individual payment ever made by the Royal Commission.

In an ironic twist of fate, Watson-Watt became a victim of his own invention when he was stopped for speeding when driving in Canada in 1956, by a policeman using an early form of the radar gun. He was fined $12.50 on the spot (approximately $135 today, equivalent to around £80).

Watson-Watt married a third time on 10th March 1966 , aged 74, to Dame Katherine Trefusis Forbes, the first director of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, which supplied the radar-room operatives during World War Two. Together they split their year between London in the winter and Pitlochry, Scotland, in the summer. Dame Katherine died in 1971.

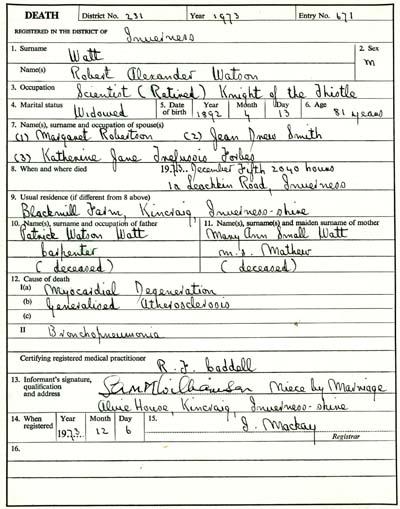

Robert Alexander Watson-Watt died two years later, on 5th December 1973, in hospital in Inverness.

Sir Robert Alexander Watson-Watt’s death entry

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Deaths, 1973, 231/ page 671.

On 2nd July 1996 the Dundee Courier reported than an anonymous floral tribute had been left at Sir Robert Watson-Watt’s grave in Holy Trinity Churchyard, Pitlochry. It read “He pointed ‘the path to freedom’. His genius helped the RAF to save this land and its people and this small tribute is from one who remembers and says thank you for today."