Scotland’s People has released online hundreds of records of prisoner-patients admitted to Perth (General) Prison Criminal Lunatic Department between 1846 and 1902. This release gives researchers the opportunity to discover patients' experiences of the institution, what treatments the patients were given and the circumstances of their illnesses. This article will look at one of the patients who was admitted to the hospital in the late nineteenth century, Andrew Reid.

Topics, words and language featured

This article features information and images from the Perth Prison Criminal Lunatic case books. These records, from the Victorian era, relate to the admission, treatment and release of prisoners with mental health issues in the 19th century. Terms and language from this historical context are present. As such there are several references to historical medical terms that are no longer medically accurate or acceptable. These include: lunatic, mad, imbecile and insane. There are also descriptions of violence.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland (NRS), Perth (General) Prison Criminal Lunatic Department Case Book, HH21/48/3 page 68

Andrew Reid’s early life

Andrew Reid was born c.1847 in Saltcoats, Ayrshire to John Reid (mason) and Mary Reid, née McBride. Andrew Reid grew up around the Ayrshire coast and can be found in Scotland’s 1851 census, aged 6, living in Ardrossan with his family.

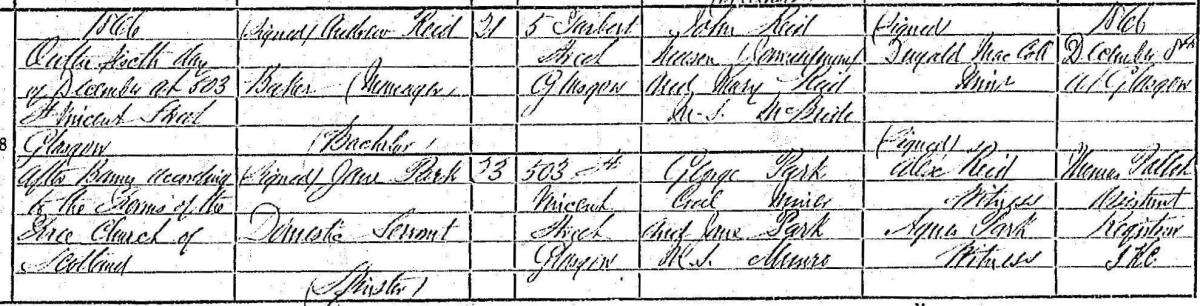

In the 1861 census, aged 16, he was enumerated living in Stevenston (east of Saltcoats) and is listed as an apprentice baker. He was apprenticed to Charles Main a baker. Also living at this address and employed as a domestic servant was Jane Park, aged 17. Andrew and Jane married in 1866 at St Vincent Street in Glasgow.

Crown copyright, NRS, 1861 census, 615/7 page 2

Reid as baker and biscuit manufacturer

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Marriages, 1866, 644/8 page 189

Andrew Reid married Jane Park in 1866 and they began a new life together in Glasgow. The 1881 census reveals that Andrew Reid and his wife had started a family, living in central Glasgow on College Street. Reid appears to have utilised his skills as a baker to start a biscuit factory. Aged 24, he is a Managing Partner, and employed '65 men, 30 Boys + 9 Girls'.

NRS, RHP6347 [available on Scotland’s People]

In the Post Office directory for 1888–9 we find Andrew Reid, biscuit manufacturer, at College Street and North Albion Street. He also owned a biscuit shop at 288 Crown Street, Glasgow.

Criminal charges

Despite his successful business, Reid’s life changed demonstrably in the late 1880s. He had paranoid episodes, believing that there was a conspiracy against him, involving those closest to him. These occurrences concluded when he was arrested in November 1888, charged with discharging his revolver into the street from his upstairs window at North Albion Street.

Before his trial, a doctor from the Royal Asylum at Gartnavel interviewed Reid at Duke Street Prison on behalf of the Procurator Fiscal to “ascertain his condition of mind”. The interview lasted an hour and a half, and their conversation was “frank and unrestrained”. The doctor appears to have formed a strong opinion of Reid during this time, reporting that he “is an acute and able man with great energy and force of character, and with a tendency to undue self-confidence and “big” notions.” Interestingly, this same doctor had “visited Mr Reid professionally” in 1887. The doctor notes that Reid was “possessed by similar ideas as to persons watching and annoying him, which led to dangerous conduct at that time also.” On that occasion he believed “his symptoms were mainly due to drinking”. Another doctor who examined Reid in December 1888 declared him “insane and dangerous” (NRS, AD14/89/218).

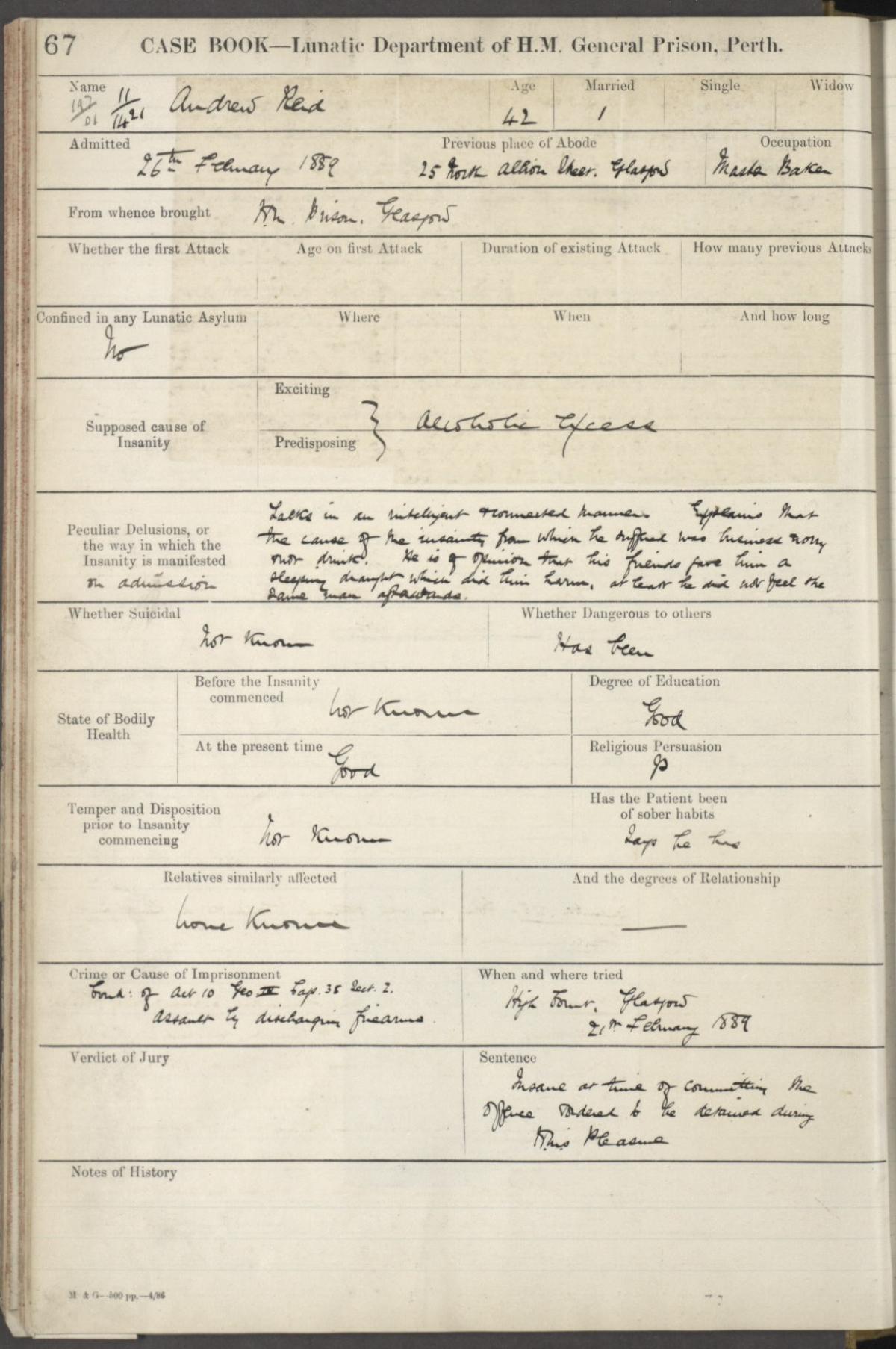

On 21st February 1889, at Glasgow High Court, Reid was charged with discharging a firearm. The jury found him “not guilty and therefore acquit him of the Crimes charged against him; and the Jury specially find that the Panel [Reid] was insane at the time of committing the crimes charged”. The court minute book also records that Reid “is not a proper object of punishment […] ordered the Panel to be kept in strict custody in the prison of Perth until Her Majesty’s pleasure be known” (NRS, JC13/11 page 66). Five days later, on 26th February 1889, he was admitted to the Criminal Lunatic Department at Perth (General) Prison and his supposed cause of insanity given as “alcoholic excess” (NRS, HH21/48/3 page 68).

Crown copyright, NRS, Perth (General) Prison Criminal Lunatic Department Case Book, HH21/48/3 page 68

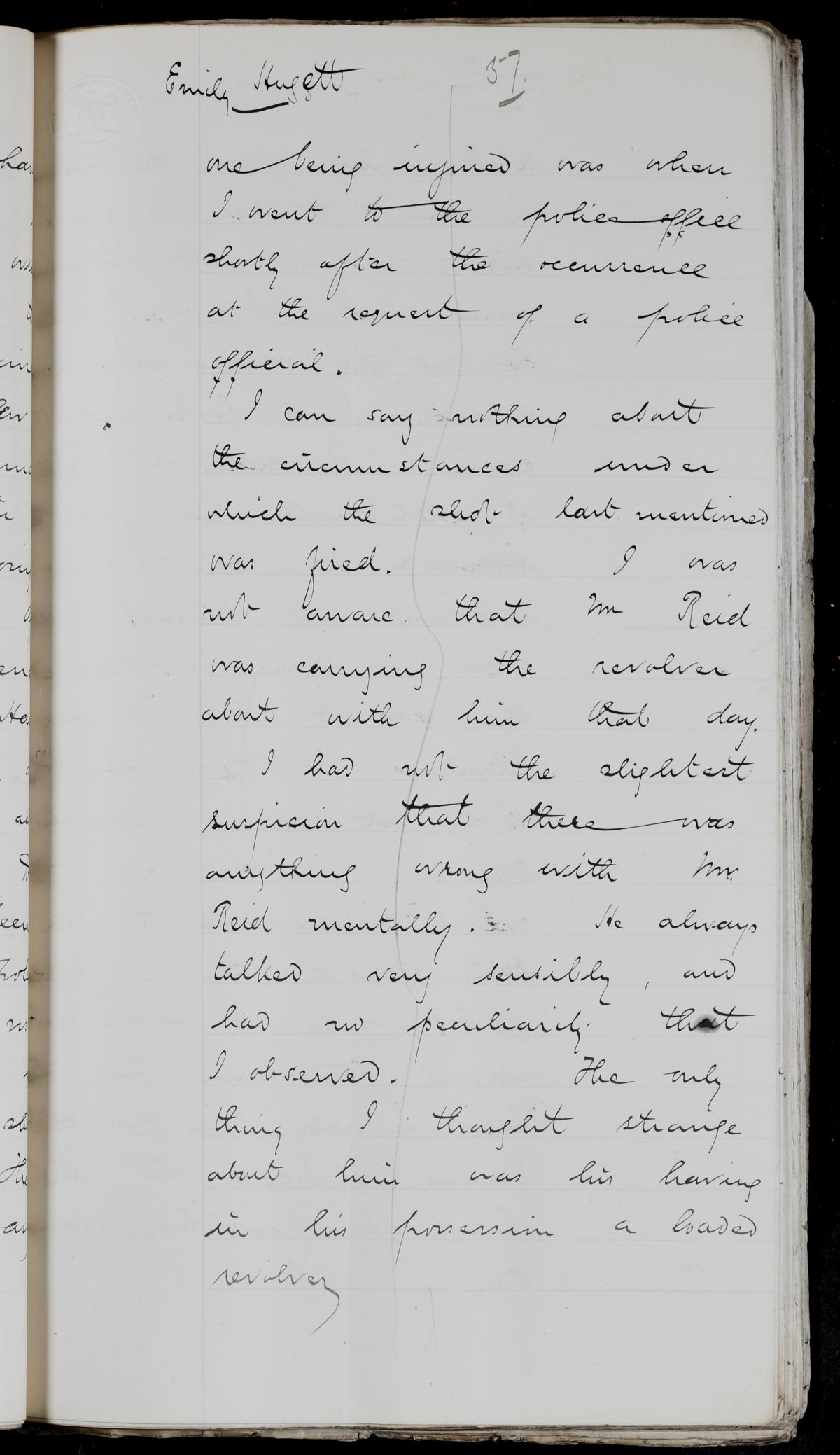

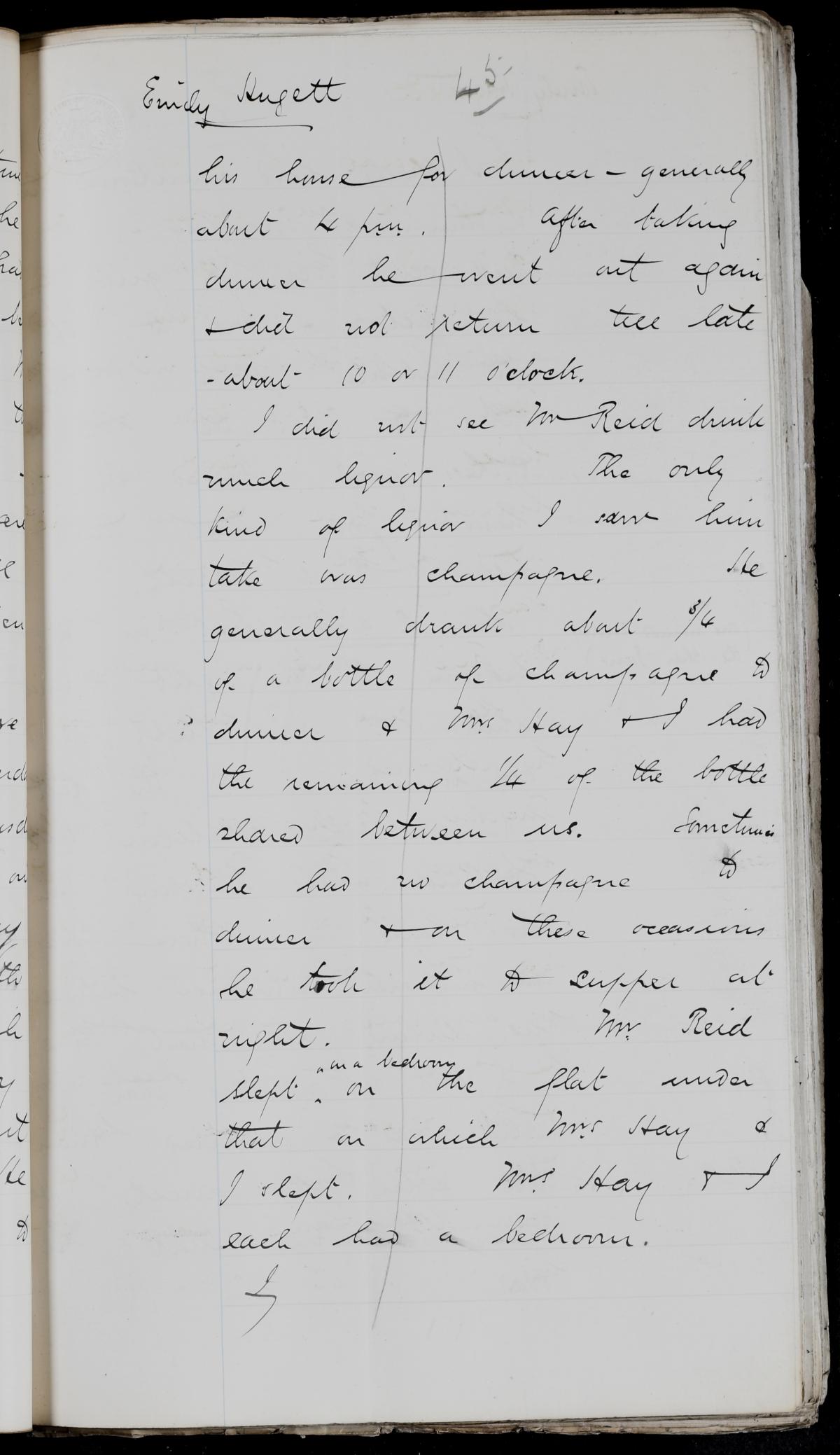

The circumstances of his crime are puzzling. A successful biscuit manufacturer, Reid had become paranoid that employees at the factory, including his own son Andrew, were conspiring against him. Reid’s mental state appears to have deteriorated in November 1888. On 8th November he dismissed the factory manager, Alexander Donald and on 20th November he “turned his wife and family out of the house” (NRS, AD14/89/217). Reid then employed two young women he had met during a visit to London to act as housekeeper and secretary. Emma Sarah Hay and Emily Huggett, who also lived with Reid, were called as witnesses to the court, to further explain what had happened on the night of 28th November. Reid had shot a revolver out of the window of his house into the street “at the danger of the lives of the lieges”. Reid did the same the following night and on 30th November he “fired his revolver at Alexander Ferguson Mennie, criminal officer [policeman], Central District Glasgow” and wounded him in the abdomen.

Crown copyright, NRS, High Court precognition, AD14/89/217

Reid’s paranoid state is further detailed in his case notes; “He is of the opinion that his friends gave him a sleeping draught which did him harm, at least he did not feel the same man afterwards” (NRS, HH21/48/3 page 68).

Reid’s time in and out of the asylum

After admission, Reid’s son, Andrew Reid junior, was interviewed by the Medical Superintendent of the institution. He said that in the last year before the offence, his father had become violent and had been tied down to prevent him harming himself or others. His son did not think his father a “drunkard” but “occasionally took drink to excess” (NRS, HH21/48/3 page 68). Emily Huggett stated in her witness statement that Reid had a taste for champagne:

Crown copyright, NRS, High Court precognition, AD14/89/217

A month after committal, Reid is noted as “Working + conducting himself well – apparently sane” and in December 1890, “no change to note” of his condition. He is liberated on 26th February 1891 to live with his son, under the guardianship of Reverend Graham.

Sequestration and South Africa

On 14th February 1900 he was “conditionally liberated” to reside with his son Andrew Reid and a cousin. Dr Campbell, a medical practitioner, was assigned to monitor Reid's condition regularly. Reid continued to be recommitted and liberated for the next two years, and lived with his son when not imprisoned in the Perth institution. The last entry relating to Reid states that “In August 1902 Reid absconded to South Africa”. We have not been able to prove this, and a death certificate has not been found for Reid in Scotland.

Sadly, by 1905 three of Reid’s sons had died of tuberculosis, including Andrew his eldest. He had married his wife just three days before his death in March 1905. Andrew Reid junior’s will had an eik (an amendment to the inventory of his estate) which involved his youngest brother, Joseph, who lived in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Did Joseph and his father emigrate to South Africa? It seems possible that the one-time patient of Perth (General) Prison Criminal Lunatic Department, Andrew Reid, along with his youngest son, Joseph, followed hundreds of other Scots at the turn of the century to start a new life in South Africa. Reid had been made bankrupt and sequestrated by the court system in the late 1890s, so the prospect of starting again far from his homeland, leaving his woes behind, must have been very appealing. We have not been able to trace Andrew Reid and his family further in the records of Scotland or abroad. Perhaps he found his fortune panning for gold or diamonds in the mines of South Africa?

Crown copyright, NRS, Commissary Court Calendar of Confirmations, SC70/20/1905 page 507

A free resource is available to access on the National Records of Scotland’s website which explores the records of people committed to the Criminal Lunatic Department in Perth; ‘Prisoners or Patients? Criminal Insanity in Victorian Scotland.’ Created as part of an exhibition of the same name, the exhibition focused on the records amassed in the prosecution and treatments of those classed as ‘prisoner-patients’, examining details of the crimes through the prisoner-patients’ own words, and the notes of doctors and prison officials as they attempted to help these men and women.

Andrew Reid’s case notes are now available to search in the Prison registers category on Scotland’s People.