In 1883 a Commission toured the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Officially named the ‘Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Condition of Crofters and Cottars in the Highlands and Islands’, they were tasked with interviewing crofters and cottars to understand and obtain evidence about their way of life and challenges facing them in relation to living conditions, rent and farming.

A crofter was (and is today) someone who paid a landlord rent to live in a croft, often working a small piece of land with a few animals grazing on common land. A cottar was a farm labourer or tenant who occupied a cottage on a croft, sometimes receiving accommodation in return for their labour.

The Commission was one of the first times that the voices of ordinary people of Scotland were captured and heard within the corridors of power. It provides an unparalleled recording of lived experiences from communities in the Highlands and Islands in this period of time. The Napier Commission (named after its chairman Francis Napier, 10th Lord Napier) travelled to 61 places where they held 71 meetings and interviewed 775 individuals, asking about 50,000 questions about their lives. Only four of those questioned were women (equating to 0.5% of the total). The Commission’s remit was broad but significant in capturing testimony, most of which was given in Gaelic before being translated. Only the English translation, which was submitted to parliament, survives.

Crofter and cottar returns, available to search on the Scotland’s People website, formed part of the evidence that the Commission gathered. These include:

- Returns by proprietors or factors of estates giving rentals and areas of deer forest, farms, crofters’ holdings, shooting, fishing and house property for the years 1853 and 1883 (NRS, AF50/6).

- Returns by proprietors or factors of estates respecting the returns of crofters and cottars giving their names, number of families and dwellings, rent, obligations in labour, service of kind, extent of holdings, arable and pasture and stock (NRS, AF50/7).

- Returns by proprietors or factors of estates giving names of cottars, whether resident on a croft or not, rent and to whom paid, occupation or means of subsistence (NRS, AF50/8

Access can be made either via Virtual Volumes, where records are free to browse, or through the new Crofters and Cottars (Napier Commission) search form, which is free to search with a cost of two credits to view an image of the original record.

For more information about how to use these records please see our guide.

A century prior to the Napier Commission, landowners triggered socio-economic shifts, breaking the historic bond between crofters and cottars and the land they worked. The ‘Highland Clearances’, which took place c.1750 to c.1860, witnessed the eviction of tens of thousands of people from their homes to free up land for more profitable sheep farming. Many people sought a new life in Australia, Canada and America, or moved to major Scottish cities for employment. Those that remained in the Highlands experienced periods of starvation and economic hardship alongside the pain of losing their traditional ways of life.

By the early 1880s, the simmering discontent felt by crofters at their treatment began to show through physical action and acts of agitation. Excessively high rents imposed by landlords deliberately forced tenants off areas of land. It pushed them towards overcrowded townships which were often bounded by large and fertile areas used for sheep farms and deer forests. A lack of security of tenure, the collapse of the kelp industry, temporary downturns in the fishing industry caused by bad weather, crop failures and harsh winters only encouraged feelings of demoralisation.

Rent strikes and land seizures began on Skye and spread throughout the crofting counties. Sheriff officers who served eviction notices for non-payment of rent were assaulted by crofters who protested high rents and forced evictions. The subsequent arrest of five crofters from the Braes district of Skye resulted in the ‘Battle of the Braes’ in April 1882. The foundation of the Highland Land Law Reform Associations in 1882 and 1883 gave the unrest a political direction. They enabled contact between crofters and radical politicians and encouraged crofters to give evidence to the Napier Commission. The strong support the Associations received from the crofters led to the election of four crofting MPs in the 1885 General Election.

A majority of those giving evidence to the Commission were from the lower classes, for example 72% of witnesses who appeared in Skye (124 of 172) were described as crofters or cottars, and, similarly, 71% (111 of 157 witnesses) in the Outer Hebrides. Testimony came from crofters, cottars, fishermen, teachers, doctors, clergymen, factors and proprietors. Some communities chose an individual to represent them with pre-prepared statements relating to their specific situations.

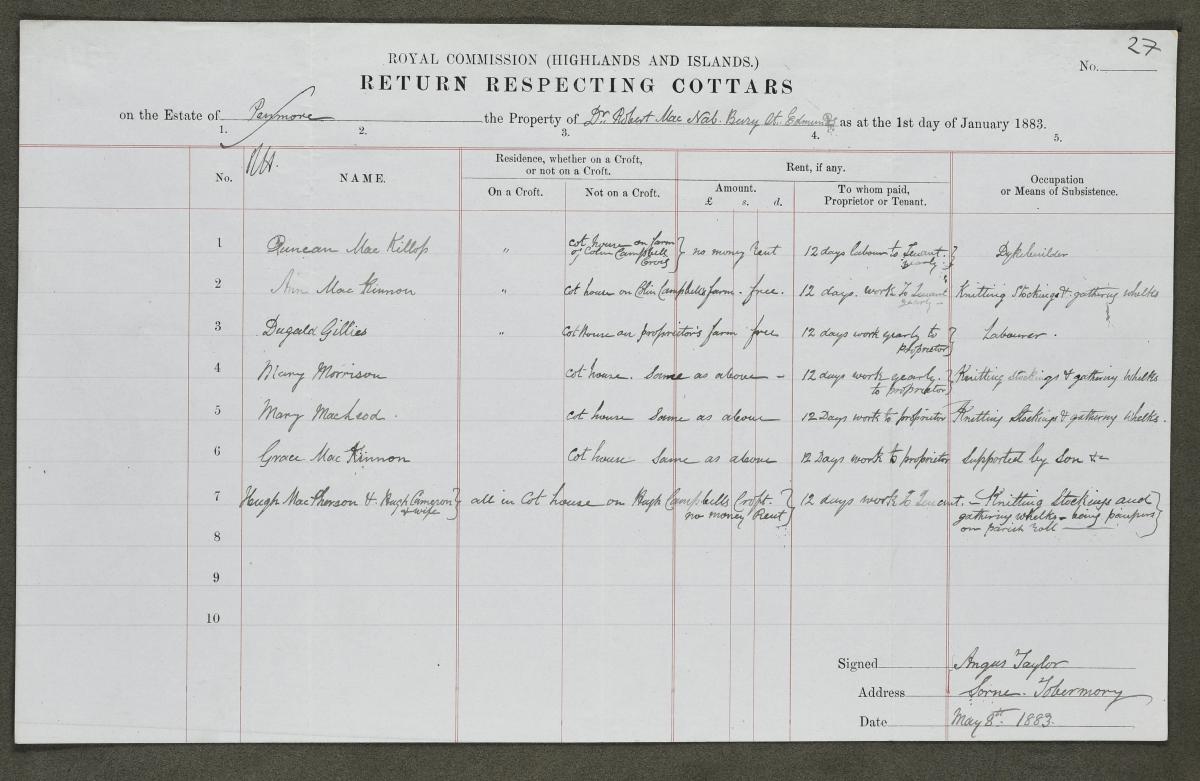

The crofter and cottar returns gathered contemporary economic and ethnographic details of the lives of the local people in the Highlands and Islands. This example, for the estate of Penmore, Mull, in January 1883, showed the cottars’ means of subsistence. Of seven cottars listed, four of them (women) earned a living by knitting stockings and gathering whelks, while another was supported by her son.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland (NRS), Napier Commission, AF50/8/1 image 27

Crofts could not support tenants all year round in the manner of their usual work and people had to be adaptable in the ways they earned money. For example, when the Napier Commission arrived in Ullapool, they found it mostly empty: over 900 of the inhabitants had temporarily moved along the east coast in the fishing trade, and others had taken work in the tourism trade, in employment such as domestic service, innkeeping and working as ghillies.

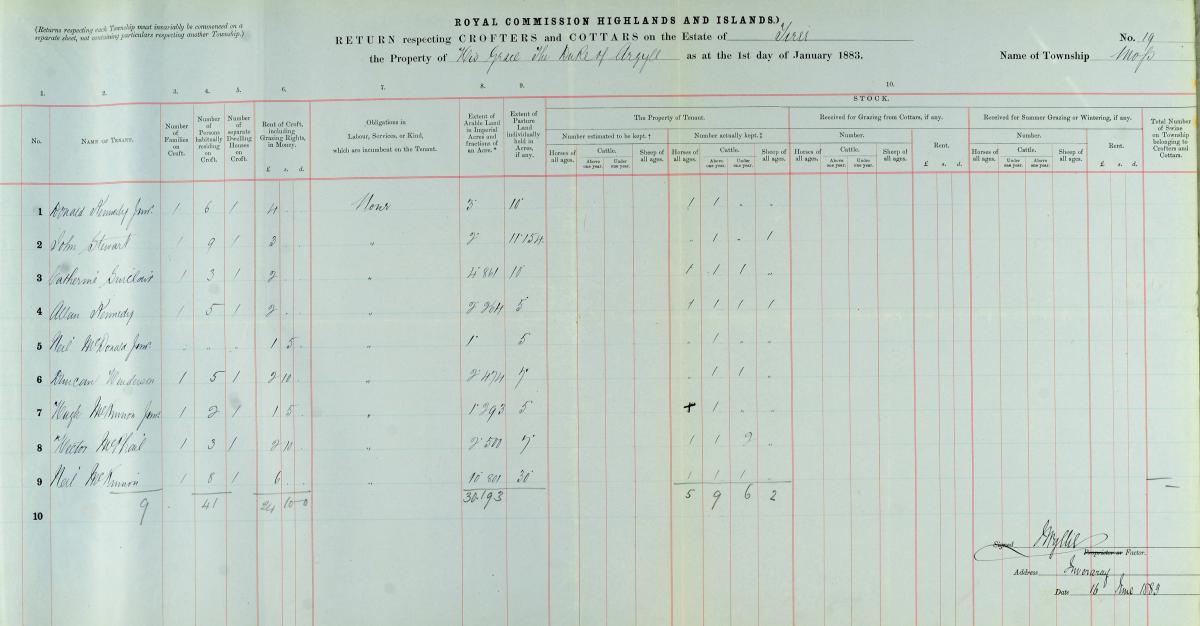

The returns also provide details of animals owned or kept by the crofters and cottars on various estates. The return of crofters and cottars of Moss township, Tiree, in January 1883 shows the extent of their crofts and the number of cattle kept. One crofter had over six acres of arable land, one had four acres, and the other eight crofters had two or three acres. The crofter with six acres kept two horses and two cows; all the others kept one of each.

Crown copyright, NRS, Napier Commission, AF50/7/1 image 54

Some tenants felt that landowners had broken with tradition, disrupting the connection between people and the land, and the relationship between tenants and landlords, through the process of evictions. The Gaelic word ‘Dùthchas’ describes an understanding of land, people and culture and the connections between them all. Highlanders and Islanders spoke of a right to live and work the land from ‘time immemorial’. For centuries they had supported their chief or landowner, paid fair rent and provided military service when called upon. They believed that this should be rewarded with security of land.

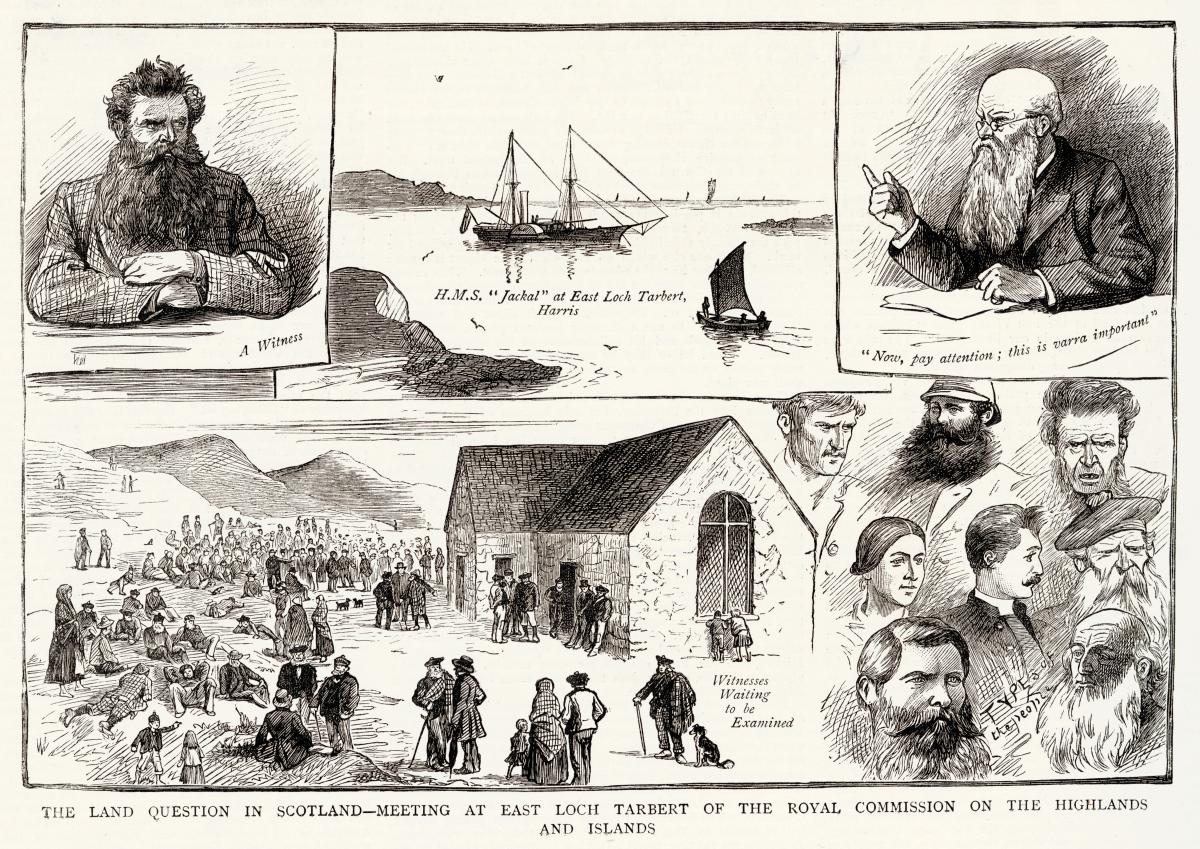

© Illustrated London News Ltd. / Mary Evans

Some people giving evidence as part of the Napier Commission sought reassurance that this would not lead to their eviction. One example was Angus Stewart, the first crofter to be examined by the Commission on 8th May 1883. He requested that "I should have the assurance that I will not be evicted from my holding by the landlord or factor, as I have seen done already…I cannot bear evidence to the distress of my people without bearing evidence to the oppression and high-handedness of the landlord and his factor.’ In return, he was told ‘It is impossible for the Commission to give you any absolute security of the kind which you desire. The Commission cannot interfere between you and your landlord, or between you and the law, but we trust that no act of oppression or severity would ever be exercised towards you or any one else by the landlord in consequence of your courage and goodness in telling the absolute truth." Angus went on to give his evidence just as many others did.

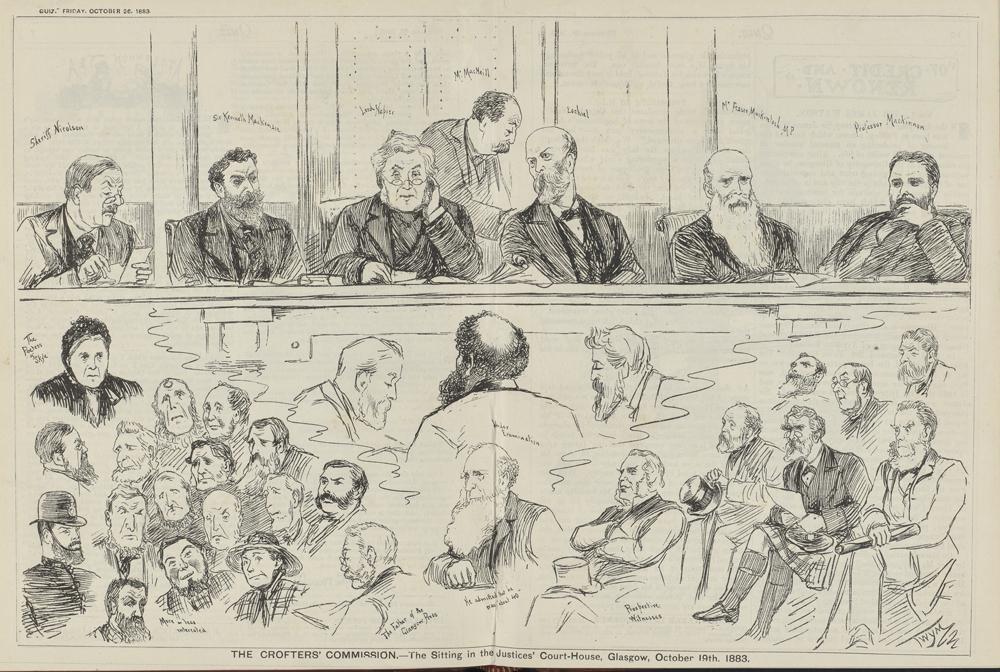

Image from ‘Quiz’, 19th October 1883. Courtesy of National Library of Scotland.

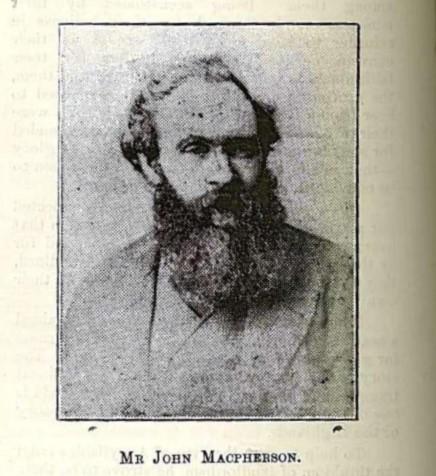

John MacPherson

Public domain image. Available to view online

One man who appears in the returns is John MacPherson. Known as the ‘Skye Martyr’ he lived on the Glendale estate on the island of Skye, and led the crofters’ land struggle in the district. He and others resisted the system of landlord rule, resulting in their arrest and imprisonment in Edinburgh in January 1883.

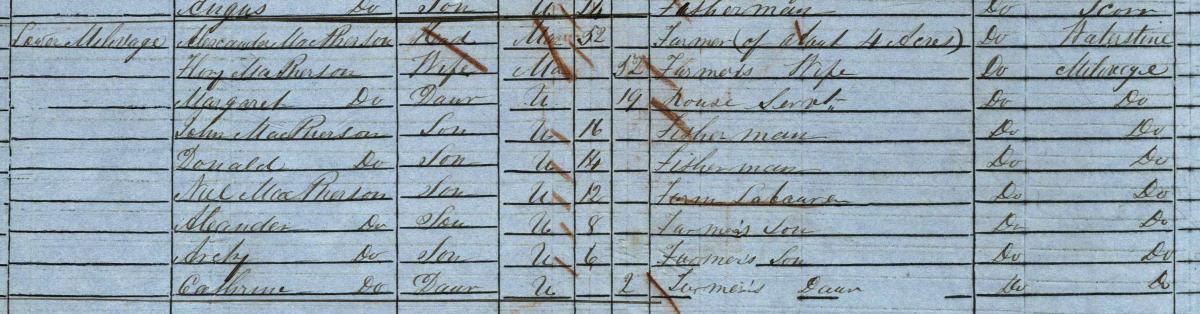

MacPherson was born around 1835 to Alexander MacPherson, a crofter, and Flora MacLeod. He grew up in the parish of Duirinish. In 1851, at the age of 16, MacPherson was enumerated in the census as having been employed as a fisherman, whilst his father tended to around four acres of farmland.

Crown copyright, NRS, 1851 census, 110/6/7 page 7

John married Margaret McLean, the daughter of a crofter from Duirinish, on 9th March 1865.

![The marriage entry of John MacPherson [McPherson] and Margaret McLean Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Marriages, 1865, 110/7 page 4](/sites/default/files/styles/maximum_size/public/2025-10/1865%20marriage%20colour%20crop.jpg?itok=Q1NCYaqI)

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Marriages, 1865, 110/7 page 4

Between 1868 and 1875, John and Margaret had five children together: two girls and three boys. Margaret died at her home at Lower Milovaig, Glendale, Duirinish, on 27th January 1876, aged 36, from fever.

The following year, on 19th June 1877, John married 38-year-old Mary Mackinnon, also from Duirinish.

It was around this time that feelings of injustice at the treatment of cottars and crofters had become especially high. The crofting community in Skye decided to take action when further common grazing land was made inaccessible to their animals. A group of men, led by MacPherson, returned their animals to graze on Ben Lee – a hill on Skye which had been taken from crofters in 1865 – and refused to pay rent to their landlord, Lord Macdonald, until the lands were returned to them. Eviction notices were issued and, in retaliation, the protestors attacked officials on 19th April 1882 in what became known as the Battle of the Braes.

A report written on 22nd April 1882 by William Ivory, Sheriff of Inverness-shire, to the Lord Advocate described the incident:

“The crofters… seeing their companions thus hurried off, they, along with a large number of women and children, attacked us furiously first with curses, and then with sticks, stones and other missiles.” (NRS, GD1/36/1/3/52 pages 2-3)

Five crofters, including MacPherson, were imprisoned for two months.

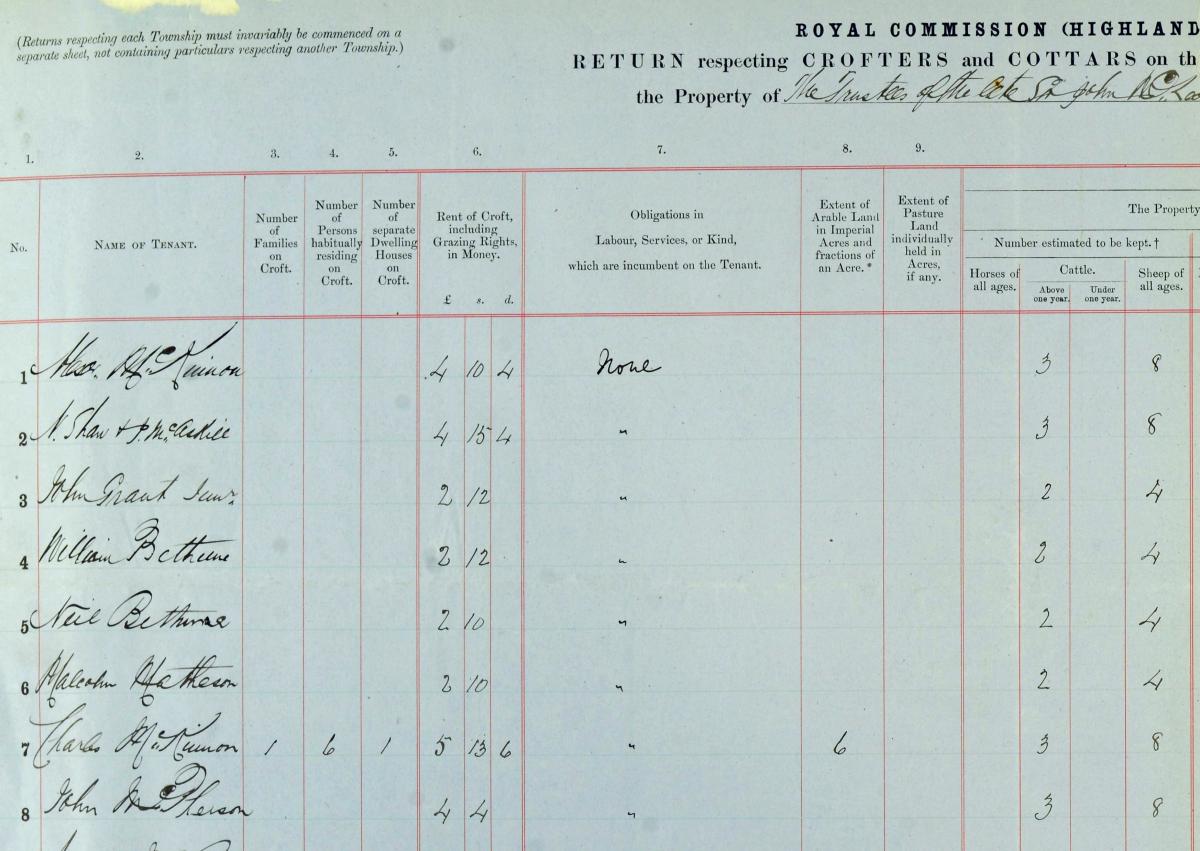

John returned to his croft in Duirinish and is recorded in the return for the estate of Glendale dated 27th April 1883. The property and land John occupied belonged to the trustees of the late Sir John McLeod and valued at £4 4 shillings. John kept three cattle above the age of one-year-old, and eight sheep "of all ages."

Crown copyright, NRS, Napier Commission, AF50/7/7 image 18

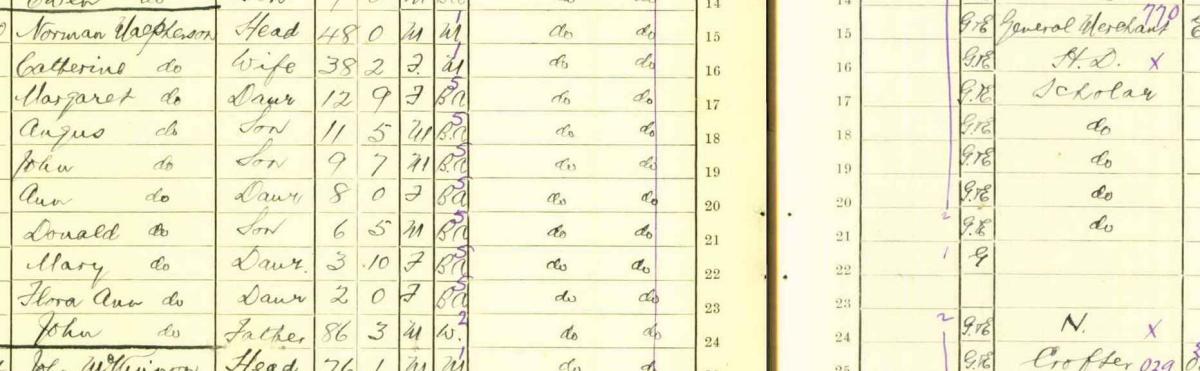

By the turn of the 20th century, John was working as a ‘crofter and steamboat agent’ in West Duirinish. He lived with his wife Mary, their son Norman, daughter Mary and other family members and boarders.

After the death of John’s wife Mary in 1906, he continued to live as a crofter in West Duirinish with his son Norman and family.

Crown copyright, NRS, 1921 census 110/1 11 page 2

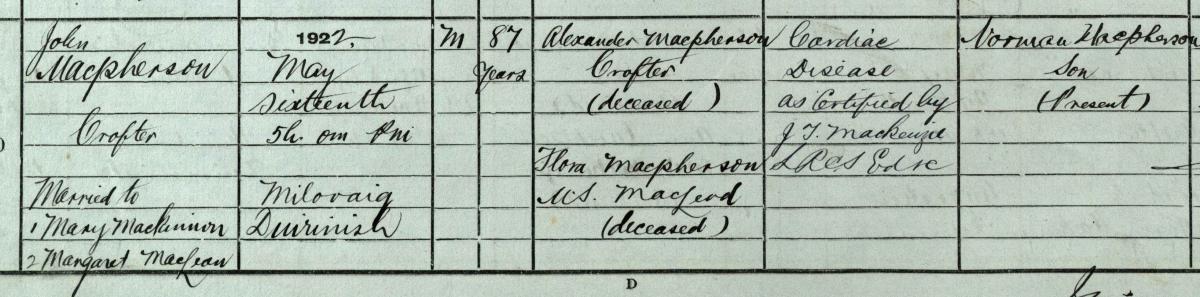

John died in Milovaig, Duirinish, Isle of Skye, on 16th May 1922, aged 87.

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Deaths, 1922, 110/1 30 page 10

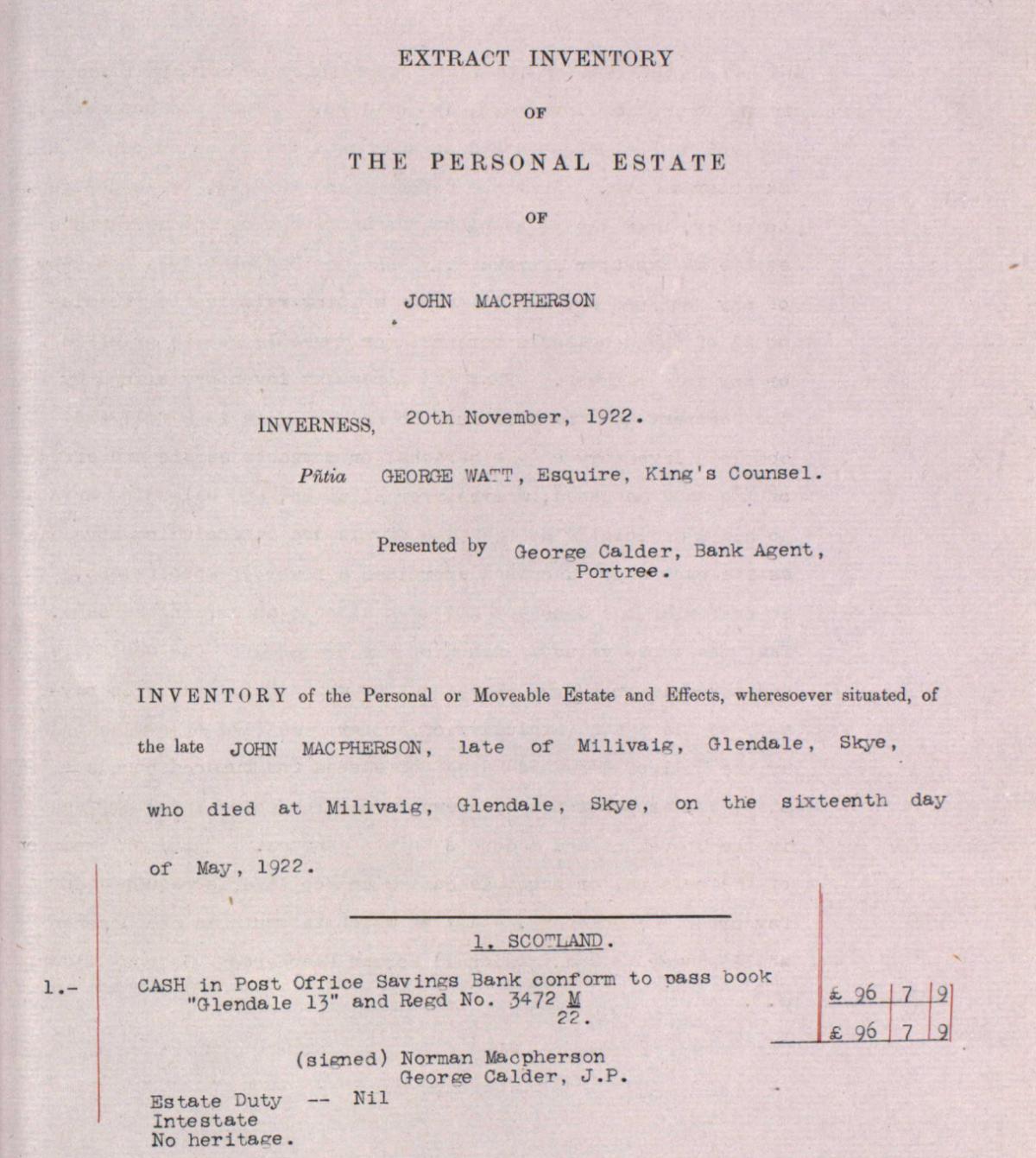

An inventory of John’s possessions at the time of his death records that he held cash in a Post Office savings account to the amount of £96 7 shillings 9 pence. According to The National Archives currency converter this is worth approximately £2,800 today.

Crown copyright, NRS, Wills and Testaments, SC29/44/64 image 911

The 1880s witnessed the catalyst for a period of change through increased rights for crofters and cottars in Scotland, thanks in part to the testimonies of communities, the evidence provided by the Napier Commission, inclusive of the crofters and cottars returns.

The Commission’s report was published in April 1884. For the crofters, it unsurprisingly fell on the side of the landlords. Although it recommended that fair rents should be established, it only suggested security of tenure to those whose annual rent was valued at £6 or above. This only supported around 10% of the crofting community.

Two years later, however, The Crofter Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886 was passed. It granted security of land tenure to crofters (making further clearances impossible in the way they had happened before), enabled crofts to be passed to descendants and ensured that a standard and reasonable rent was set out. It also established the Crofters Commission, a land court which ruled on disputes between landlords and crofters, although in reality it lacked serious power. It failed, however, to include much provision to make more land available to tenants and made no provision for cottars and squatting populations, which resulted in further land seizures. Furthermore, the Act did not enforce the return of land previously taken from crofters. Despite limitations, this was a watershed moment for the rights of those living on the land.

For more information on the crofter and cottar returns please see our guide.

Further reading

The University of the Highlands and Islands - The Napier Commission

The Angus Macleod Archive - The Napier Royal Commission of Inquiry

Witnesses to the Napier Commission on the Outer Hebrides

Billy Clelland, The Napier Commission and the 'Crofters' War' in Tiree