To commemorate the centenary of the Battle of the Somme we present the stories of five Scots out of the 21,392 soldiers in the British forces who were killed in action on the first day, 1 July 1916. And a French soldier with Scottish connections who was also killed that day reminds us that the Somme offensive was part of a wider Allied campaign. Using various records in ScotlandsPeople, we focus on these soldiers’ testaments: not only wills, but also inventories of personal estates, which can also reveal vital information.

Learn more about Wills and Testaments and the separate series of Soldiers’ Wills in our guides.You can also read about two other Scots on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, and more stories about soldiers who died during the 141 days that the battle lasted.

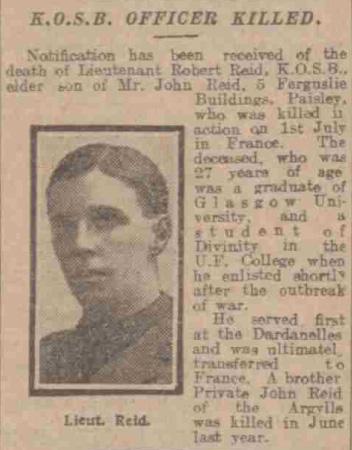

Second Lieutenant Robert Reid, 1st Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers

A junior officer in the 9th Battalion of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers regiment (KOSB), Robert Reid was born in 1890 and grew up in Paisley, the son of John Reid, a sub-manager in a thread mill, and Elizabeth Greig, of 5 Ferguslie Buildings. He had three sisters and one brother.

Rather than following his father into the industry that made Paisley Scotland’s leading textile centre, Robert studied at Glasgow University, graduating in 1912 with a degree in Social Economics and Political Philosophy, and began divinity studies at the United Free Church of Scotland College in Glasgow. In 1914 he volunteered for the army, was placed in the 9th Battalion, KOSB, formed in November 1914, and commissioned as an officer.

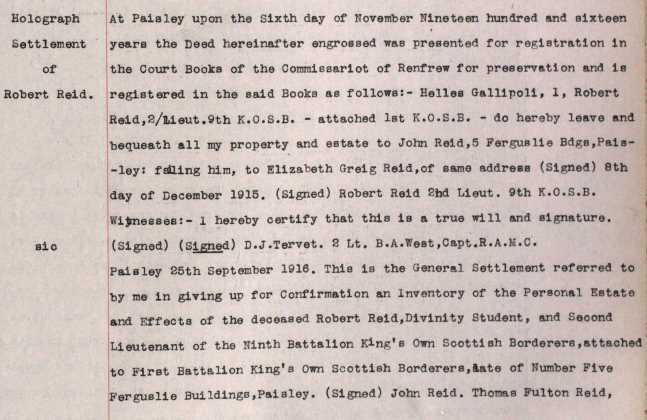

From the will that Robert wrote on 8 December 1915, witnessed by two brother officers, we learn that he was then serving with the 1st Battalion, KOSB, at Helles, Gallipoli. No doubt he had been posted to make up for the heavy casualties experienced by the battalion at Gallipoli. After the battalion was evacuated to Alexandria in Egypt, in March 1916 it was transferred to the Western Front.

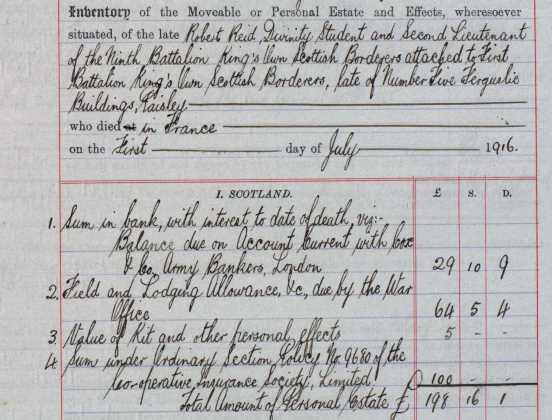

Reid’s original will was ‘holograph’, and for it to be accepted as authentic, his father and his sister, Margaret Gordon Reid, both testified that the will was in his handwriting. A small gem of information is that Margaret is described as ‘Dressmaker and Munition Worker’, so she was also doing her bit for the war effort. Robert’s estate was typical for soldiers of moderate means and was valued at £198 (around £8,500 today). It consisted of an insurance policy for £100, and his army pay and allowances.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) can be a helpful starting point for identifying a soldier’s next of kin and home address, as well as their place of burial or commemoration. The CWGC records show that Robert’s father requested the words ‘Faithful Unto Death’ be inscribed on the grave stone, and the same for his younger son John, a private in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, who died elsewhere on the Western Front in June 1915. He also features in Glasgow University’s Roll of Honour.

Notice of Lt Robert Reid’s death, ‘The Daily Record’, 10 July 1916

Republished courtesy of The British Newspaper Archive

Will of Lt Robert Reid, 1915

National Records of Scotland, SC58/45/22, page 181

Inventory of the personal estate of Lt Robert Reid, 1915

National Records of Scotland, SC58/42/85, page 533

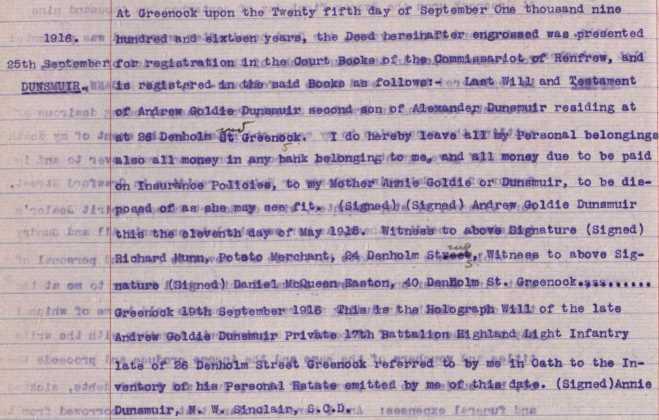

Private Andrew Goldie Dunsmuir, 17th Bn, Highland Light Infantry

Andrew was born in Clydebank, the son of Alexander, a marine engineer, and his wife Annie Dunsmuir, and he had three brothers and two sisters. In peacetime he lived at 39 Kelly Street, Greenock, and worked as a clerk in a sugar refinery, part of what was once a massive industry in the town. We know this from the census and statutory registers, and in another ScotlandsPeople record, the Service Returns of Deaths, we learn Andrew’s service number, 15562, his unit, the 17th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry, and his age when he was ‘K in A’, or killed in action, in France. Such basic facts can also usually be found on the CWGC website. Learn more about the Service Returns of Deaths which are part of the Minor Records.

Andrew died testate, and his will and inventory, which are available to view on the ScotlandsPeople website, reveal telling details. He wrote his will on 11 May 1915, shortly before his battalion left Scotland for training in England. He was thinking of his mother’s welfare, as he left to her all his belongings and money, which amounted to £168 (around £7,200 in 2016).

In November 1915 the 17th Battalion, known as The Glasgow Chamber of Commerce battalion, embarked for France, along with the 16th Battalion and other units of the 32nd Division. The ‘Glasgow Commercials’ suffered heavy losses on the first day of the Somme. The CWGC website records that Andrew’s name is on the Thiepval Memorial, which commemorates British and empire soldiers who have no known grave, an indication in itself of the effects of the fighting.

Will of Private Andrew Dunsmuir, 1915

National Records of Scotland, SC53/47/16, page 620

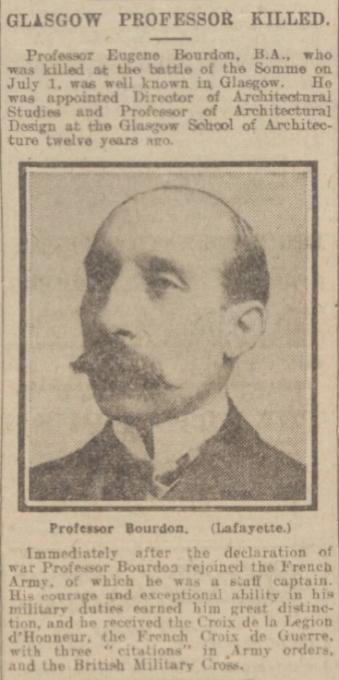

Captain Eugene Bourdon, 78th Brigade of the French Army

One of the more unusual stories to emerge from the records of soldiers who died on 1 July 1916 is that of Eugene Bourdon, professor of architectural design at the Glasgow School of Architecture from 1904 until 1914. The Roll of Honour at Glasgow School of Art records his name, and there is also a memorial to him in the School. The online Dictionary of Scottish Architects provides more information about his professional career.

At the outbreak of war, Bourdon, aged 44, was a Reserve Staff Captain in the 78th Brigade of the French Army. He was mobilised and returned to France for war service. By the time of this death his courage in action had been awarded the Croix de la Legion d’Honneur, the Croix de Guerre and the British Military Cross.

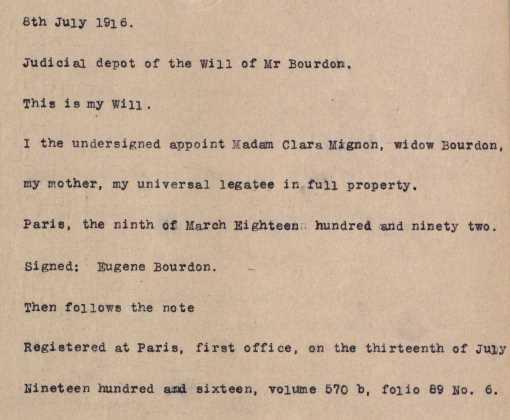

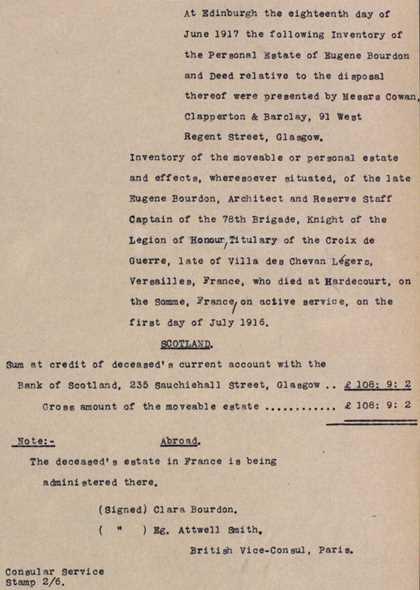

Bourdon’s lengthy testament reveals much about his family and professional life. Although his affairs were mainly settled in France, his will and inventory were recorded at Glasgow Sheriff Court because he owned moveable property in Scotland, consisting of £108 in a bank account in Glasgow. The inventory states that his executor was Clara Mignon Bourdon, a widow.

Surprisingly she was in fact his mother, because Bourdon, although married, had been judicially separated from his wife, Madame Claire Augustine Jouanin, since 24 July 1912. The will that he wrote in 1892, leaving everything to his mother in Versailles, was recorded both in the original French and an English translation. The testamentary documents also reveal that Captain Bourdon died of his wounds at ‘bois d’en Haut’ (High Wood) at Hardecourt, south of the Somme, after a shell exploded in a front line trench: ‘par suite de blessure par éclatement d’obus dans la tranchée de première ligne, Mort pour la France’ (NRS, SC70/4/497, pages 300-1).

Obituary notice, ‘The Daily Record’, 13 July 1917

Republished courtesy of The British Newspaper Archive

Translation of Eugene Bourdon’s will of 1892

National Records of Scotland, SC70/4/497, page 297

Inventory of Eugene Bourdon's estate, 1917

National Records of Scotland, SC70/1/596, page 414

Soldiers who died without a will

Many, probably most, soldiers who lost their lives during the First World War died without a will. But we can still build a picture of their lives through other records - in particular, the inventories in the Wills & Testaments. Here we investigate what can be learned about two soldiers who were intestate when they were killed in action on the first day of the Somme. In such cases, their testament is referred to as a ‘testament-dative’, and essentially consists of an inventory of their estate, with accompanying statements about its accuracy.

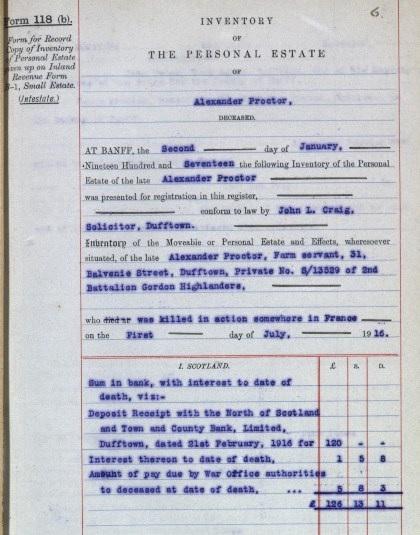

Private Alexander Proctor, 2nd Battalion, Gordon Highlanders

Alexander Proctor was born on 17 July 1885 in Castle Street, Dufftown, Banffshire, the son of James Proctor, a labourer, and his wife Isabella Edward.

Alexander died intestate, and in January 1917 an inventory of his estate was recorded at Banff Sheriff Court on behalf of his father, who sought to be confirmed as Alexander’s executor, and to inherit his estate. The inventory mentions that Alexander had £120 in his bank account, plus interest and just over £5 army pay owing, totalling over £126 (worth around £5,400 today).

The inventory also describes him as a farm servant, but ‘The Aberdeen Journal’ (21 July 1916) stated that he worked in one of the local distilleries before the war, and that he was one of four brothers serving. According to the CWGC website, Alexander was aged 30 when he was killed, and was buried at Gordon Cemetery at Mametz on the Somme front. The cemetery was created by his battalion, who buried some of their dead of 1 July in what had been a support trench.

Inventory of Alexander Proctor’s estate, 1917

National Records of Scotland, SC2/40/77, page 6

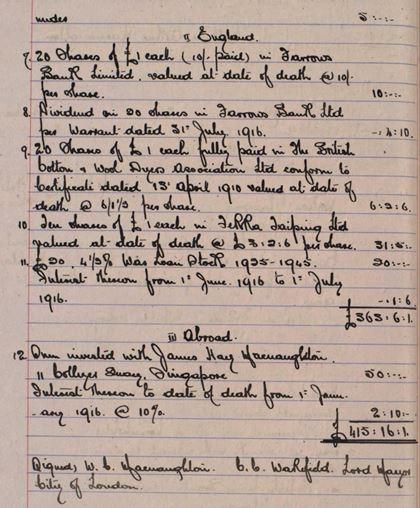

Private Callum Arthur MacNaughton, 17th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry

Callum was the son of James Hay MacNaughton and Mary Cleland MacNaughton, and was born in Pollokshields, Glasgow. In 1901 he was living with his aunts, and not his parents, at 29 Keir Street, Pollokshields. That year he left Hutchesons' Grammar School, which he had attended from 1896, and at the age of fourteen began work for a shipbroker’s firm. After seven years he started a career in finance as a cashier in a Glasgow merchant's house. In the 1911 Census he is recorded as a bookkeeper, aged 24 and unmarried. At this period MacNaughton played rugby with the Cartha Club in Glasgow, and served as its secretary, 1913-1914.

In 1914 he joined 17th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry with other men from city’s financial and business community. The battalion was known as the Glasgow Chamber of Commerce battalion, or ‘The Glasgow Commercials’. On 1 July 1916 the battalion advanced on the Somme, and MacNaughton was killed in action. Hutcheson’s School magazine noted that as a bomber he was accompanying an officer, and both were killed by machine gun fire. Two other club members in the same battalion were also killed: Sergeant James Yuill Turnbull, who won a posthumous Victoria Cross for his leadership and courage that day, and Corporal Hugh F McKenzie. MacNaughton’s name is inscribed on the Thiepval Memorial in France.

Although MacNaughton did not leave a will, the inventory of his estate helpfully reveals that he was unmarried and well off, no doubt owing to his job as a clerk with H P Buchanan, a firm of East India merchants in St Vincent Place, Glasgow. Among his foreign investments was the sum of £50 placed with his brother, James Hay MacNaughton, in Singapore. His eldest brother, William Campbell MacNaughton, a marine insurance clerk in London, compiled the inventory of Callum’s estate, which totalled £415. 16s. 1d., or about £17,800 in 2016 values. Not all private soldiers had limited means.

Detail of inventory of Callum MacNaughton's estate, 1916

National Records of Scotland, SC36/48/270, page 644

Alexander Lawrie, Edinburgh, 16th Battalion, Royal Scots

Alexander Lawrie (centre) and Royal Scots comrades, circa 1915

Courtesy of Anne McLaren

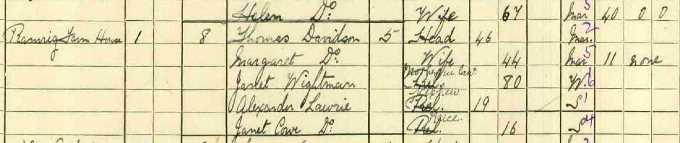

Alexander Lawrie was born in Edinburgh on 24 June 1891, the son of Alexander Lawrie, a gas works stoker, and his wife Annie Wightman. His parents had roots in the Borders, and in 1911 the nineteen-year old Alexander was living and working at Ramrig farm in Ladykirk parish, Berwickshire. The farm was worked by Thomas Davidson, who was married to Alexander’s aunt, Margaret Wightman.

Within a few years Alexander was back living with his parents at 7 Slateford Road, Edinburgh, and working as a farmer, according to the printed roll of honour of the John Ker Memorial United Free Church in Edinburgh (National Records of Scotland, CH3/1254/49). On the outbreak of war he joined up and became a private in the 16th Battalion, Royal Scots (McCrae’s Battalion) which was quickly raised in Edinburgh during autumn 1914. He served in the machine gun section, and was one of the 585 officer and men of that battalion who were killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

Three of Alexander’s brothers served in the First World War. Two survived but his younger brother John was killed in July 1918. In peacetime, John was a shorthand clerk and typist in the Burgh Engineer’s office, Edinburgh. Having served in 5th Battalion, Royal Scots, he was fighting with the 2/4th Battalion York and Lancaster Regiment at the time of his death.

Alexander left no will, nor was an inventory of his estate recorded, but the outline of his life can be traced in records in ScotlandsPeople and National Records of Scotland. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Anne McLaren, descendant of Alexander and John Lawrie’s younger sister, with the photographs.

Alexander Lawrie with horses at Ramrig, Berwickshire, circa 1911

Courtesy of Anne McLaren & Peter Herriott.

Alexander Lawrie and the Davidson family at Ramrig, 1911

National Records of Scotland, 1911 Census, 746/1/9