On 7th February 1886, the boat ‘Columbine’ struck submerged rocks off the coast of Norway. On board was just one passenger – Elizabeth Mouat from Shetland.

Elizabeth's arrival on shore marked the end of a nightmare 9 day journey from the coast of Shetland, and was a miraculous story of survival.

Elizabeth was born in 1825 in Shetland to Thomas Mouat, a shoemaker and herring fisher, and his wife Margaret Harper.

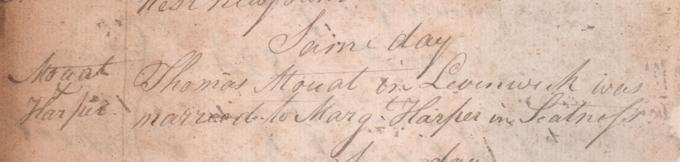

Thomas and Margaret's marriage entry. Dunrossness, Sandwick and Cunningsburgh, 9th December 1824.

National Records of Scotland, OPR Banns and Marriages, 1824, 003/30 159

In the winter of 1825 a boat, the 'Lively', bound for whale fishing in Greenland, stopped by Lerwick in need of a man to replace one of their crew who had fallen ill. Thomas volunteered. Sometime into the voyage, the ship left Greenland and disappeared in the Arctic; Thomas was never heard from again. Elizabeth was only six months old.

Her mother re-married in January 1828 to a neighbouring fisherman, Thomas Hay. They lived together in his croft house in Scatness, Shetland, where Elizabeth would live for the rest of her life with her half-brother James and his family.

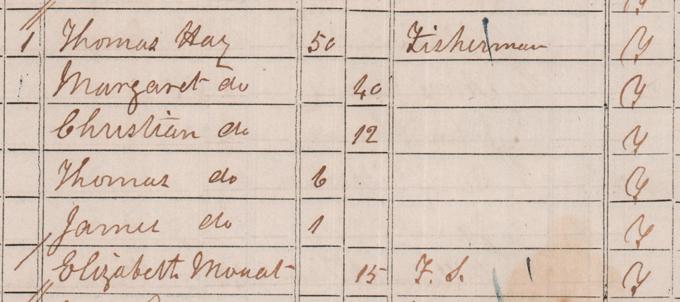

The 1841 Census recording Thomas and Margaret’s household.

National Records of Scotland, 1841 Census, 003/4/3

Elizabeth never married. She spent her younger years toiling on the land, loading peat into carts and, in the long winter evenings, producing high quality hosiery and knitted goods. Elizabeth suffered from several health issues. Around 1870, as she stopped to tether a sheep in a field on her farm, she was accidentally shot in the head with several pellets by a man shooting rabbits. Only one pellet was removed. She suffered with a limp for much of her life, and in the summer of 1885 she had a ‘stroke of paralysis’ which left her with limited mobility.

On 30th January 1886, Elizabeth decided to travel to Lerwick in order to visit the doctor and, later, her niece, and trade some of the fine hand knitted goods that she and other community members had made before returning home. Many people walked the route along the coast, but Elizabeth was reluctant to travel by foot due to her weak leg.

The boat used for the journey was ‘The Columbine’. The ship's captain warned that it would be best to delay the journey; it was expected to take 2-3 hours and stormy seas were forecast. Anxious to go, however, she convinced the captain to sail. As predicted, the weather turned. Elizabeth sheltered below deck and after a while thought that the boat had struck some rocks, but in fact the boat was being tossed by the violent sea. In a tragic turn of events, the captain, James Jamieson, was thrown overboard and drowned.

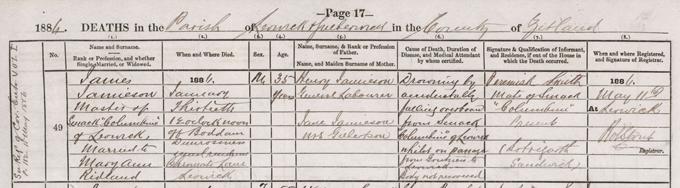

James Jamieson's death entry. Cause of death is given as 'drowning by accidentally falling overboard from Smack 'Columbine' of Lerwick whilst on passage from Grutness to Lerwick. Body not recovered.

National Records of Scotland, Statutory Register of Deaths, 1886, 005/49

The other two remaining crew members launched a small lifeboat to try to find him, without success. They realised with horror that the 'Columbine' was unreachable and headed for shore to raise the alarm. Two steamers were sent out to search for her with no success. Press agency telegrams were sent to the British Consul in Norway but searches of the area were halted on February 1st.

On board the 'Columbine', Elizabeth recognised that she was alone. She was trapped below deck with water being washed into the hold and was soaked through. For over a week, she didn’t sleep or lie down, but maintained a sitting posture, holding onto a rope to keep from being thrown around, and suffering terrible blisters on her hands.

As the seas calmed after a couple of days her sea sickness subsided, and she became hungry. Unprepared for a long voyage, she had only packed a bottle of milk and 2 biscuits. Elizabeth made her supply last for days; unable to reach provisions held at the front of the upper deck, she carefully made her supply last for days and licked condensation off the inside of the windows to try to stay hydrated.

Despite wearing a thick sailor’s jacket, Elizabeth still suffered from the cold and in her weakened state was unable to move much aside from peeking over the open hatch onto deck to try to spot land or passing ships. Newspapers later reported that she hadn’t given way to ‘violent grief’ but had endured her time on board with calmness, and fortitude.

About 8 o’clock on the Sunday morning, the vessel reached the shore of the small island of Lepsøya, about 12 miles north of the fishing town of Aalesund on the coast of Norway.

Elizabeth was able to look out from the hatchway, raise her arms and scream for help. She later recalled how a group of young men nearby saw her and sought help from local fishermen. One reached the boat, climbed on board and pulled her to shore with a rope.

Elizabeth was given care and attention by the villagers who gave her warm, dry clothing and brought her to stay in their home. An Englishman, Mr Bulley, who ran a cod liver oil factory on the island, visited Elizabeth and translated her story for the villagers. He took her into his own home in Kjersstaf where was given medication and nutritious food to aid her recovery.

On 15th February, Elizabeth left Lepsøya to begin the journey back to Shetland.

Elizabeth became a celebrity of her time. She reached Edinburgh on 24th February and Shetland on 16th March. At all stages of her journey the public crowded to see her and back in her croft she welcomed people for years to come. A local bookseller, H Morrison, sold photographs of her as souvenirs.

Newspapers also reported that Queen Victoria was also ‘much touched by the account of the sufferings of Miss Mouat, and was pleased to learn by her brother’s letter…that she is recovering her strength’ and forwarded Elizabeth a cheque for £20. Other financial donations and gifts were sent by members of the public to Elizabeth in the months following the event, to help provide for her in her advancing years.

The British Government awarded Elizabeth’s rescuers medals and sent their sincere thanks to the islanders. The bay at Lepsøya, where the boat ran aground, was named ‘Columbinebukta.’

Elizabeth spent the next 30 years quietly knitting in the family croft. She died there on 6th February 1918, the 32nd anniversary of her last night on the Columbine.

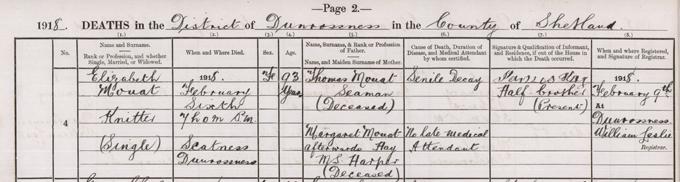

The death entry of Elizabeth Mouat, 6th February 1918.

National Records of Scotland, Statutory Register of Deaths, 1918, 003/1 4