The beginnings of poor relief

The kirk session and poor relief

Raising funds

The Poor Law (Scotland) Act 1845

Throughout the centuries the church has played a key role in the lives of the Scottish population. Amongst its responsibilities were the management of education, the recording of births, deaths and marriages and disciplining errant parishioners for offences such as drunkenness, swearing, Sabbath breaking and sexual misdemeanours. A further duty was the provision of poor relief to parishioners; this article looks at how this evolved.

The beginnings of poor relief

In the medieval period the functions of social welfare, including poor relief, were mostly carried out by hospitals maintained by monastic or burgh institutions. Supporting the poor was largely perceived as a spiritual act of Christian charity. The Scottish Parliament and Privy Council made many statements and declarations relating to the problems of the destitute and the ill. Rather than advocating support for the poor in general, these concerns usually came from a desire by the landowning class to maintain a stable society and keep their lands under cultivation by their tenants and cotters, even when catastrophes such as epidemics, persistently severe weather and crop blights made subsistence farming difficult or impossible in certain areas of Scotland at various times.

Various acts of parliament were passed to deal with poor relief in Scotland, and curb the prevalent issue of begging. For example, a 1425 act drew a distinction between the able-bodied beggar and those unable to earn a living for themselves. A century later, a 1535 statute allowed parishes to issue tokens to beggars, to try to prevent vagrancy. Children were not immune from a precarious existence; if their parents were unable or unwilling to find work then they became vulnerable to starvation and homelessness. In 1579 an act was passed allowing any heritor to take a pauper child aged between five and 14 into his service; girls had to remain until they were 18 years old and boys until they were 24.

The kirk session and poor relief

Following the Scottish Reformation in 1560, the religious hospitals associated with the monasteries were largely abandoned and the Reformed Kirk was concerned about the poor from both a religious and moral sense. The First Book of Discipline declared that each parish should care for its own poor; at least those such as widows, the elderly and those whose age or disabilities left them unfit to work.

Kirk sessions were also responsible for supporting abandoned babies (sometimes recorded as ‘exposed’ within the records). Factors such as the shame of conceiving out of wedlock and the harsh realities of poverty, meant that many illegitimate children were left to be brought up by the parish. The demand for financial support at times resulted in a lack of poor relief funds and the kirk session were often anxious to locate the parents, as much for the child's sake as for monetary reasons.

On 24 December 1721, for example, Inverurie kirk session minutes record that an orphan was found 'exposed'. The following day a search for the mother was to be undertaken and all 'who may be supposed to have child...it will give ground to suspect them as guilty, in regard such as are innocent will look on it as a privilege to be searched, that their innocence may appear.'

The Inverurie kirk session minutes record the plans to search for the mother of the exposed orphan

National Records of Scotland (NRS), Inverurie kirk session minutes, CH2/196/2 page 47

An estimate for the cost of maintaining the poor in each parish was compiled by local authorities and the administration for this was undertaken by the kirk session and heritors. Under this system, people requiring support due to factors such as age or illness, could appeal to the last parish in which they had lived for seven years or the parish of their birth. Married women could also adopt their husband’s parish of birth or residence.

In 1782, Margaret Henderson, an elderly parishioner in Cleish, was given ‘two pound four shillings and six pennys and on regard of her great age and infirmity the session allow her a pension of one shilling per week till further orders’ (NRS, CH2/67/7/121, page 120.) The previous year a family were given financial aid as the head of the household was serving in a ‘regiment and his wife by reason of her bad state of health being unable to do anything almost for the support of four children, the session...agreed to allow them one shilling per week.’ (NRS, CH2/67/7/118.)

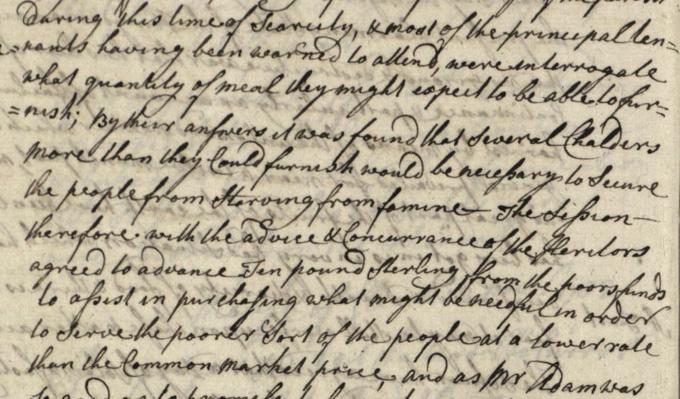

Aid was also given to communities during exceptional circumstances. Cleish kirk session minutes, on 3rd January 1783, record that aid was provided during the harsh winter of 1782-83 when there was a critical shortage of meal and grain. The minutes state that ‘several Chalders more than they could furnish would be necessary to secure the people from starving from famine. The session therefore with the advice and concurrence of the Heritors agreed to advance 'ten pound sterling from the poor’s funds to assist in purchasing what might be needful in order to serve the poorer sort of the people at a lower rate than the common market price’.

(A ‘chalder’ or ‘chaldron’, from the French ‘chaudron’ meaning a ‘kettle’, was a measure of dry volume.)

Detail from a page from Cleish kirk session recording instructions to provide aid to the community.

NRS, Cleish kirk session minutes, CH2/67/7 page 121

Raising funds

Monies for poor relief were collected via church door donations after each service, through mortcloth dues (the hiring of a ceremonial cloth to cover a body at a funeral), and fines for inappropriate behaviour and mortifications (money donated or bequeathed to the Church). If there happened to be a shortage of funds, the parish could also impose donations by assessing heritors. This assessment was strongly resisted by the heritors, for fear of the precedent which it would create, and the curious situation arose in many parishes where the heritors (as members of the kirk session) paid a voluntary contribution rather than see the poor’s funds drop to such a level that a legal assessment would be imposed on them (as landowners in the parish).

Duddingston kirk session, like many others, rented church pews to generate funds. In July 1787 they noted ‘as the poors [sic] funds were extremely low the session had agreed to raise the price of the seats.’ This generated eight pounds, seven shillings and six pence, which went towards the maintenance for those on monthly allowance.

The names of thousands of poor still survive, recorded on poor’s rolls which often indicate the types of disability or illness and amounts paid to paupers. The considerable cost of maintaining paupers meant that thorough checks were undertaken before relief was provided. Grants were augmented by gifts in money or kind from the charity of family, friends and neighbours, and a certain stigma was attached to the receipt of public relief. The whole intention was to avoid the creation of a climate where relief was considered as either a desirable or a moral entitlement.

In 1815, for example, Thomas Kennedy, a Whig lawyer, stated that ‘every individual [in Scotland] is bound to provide for himself by his own labour, as long as he is able to do so, and that his parish is only bound to make up that portion of the necessaries of life, which he cannot earn or obtain by other lawful means.’

The rapid development of industrialisation in the nineteenth century accelerated economic slumps and periods of depression which in turn created unemployment and poverty. Trades such as weaving were particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in prices and to the competition from machinery. It became clear that too many people were struggling to survive with little or no support.

The Poor Law (Scotland) Act 1845

The General Assembly of 1841 called for an official inquiry into the state of poor relief and in January 1843 a Royal Commission of Inquiry was appointed which recommended reform. A lengthy questionnaire was sent to every parish in Scotland, and from the information these provided, as well as from personal visits to every presbytery, a report was published in 1844; The Royal Commission on the Poor Laws. This led to the introduction of a new civil system of poor relief administered by parochial boards in parish areas. These were superseded by elected parish councils in 1894, replaced by district councils in 1929 and abolished in 1974. The Commissioners concluded that under the current system ‘the allowances [for relief] are often inadequate… and that the amount of relief given is frequently altogether insufficient to provide even the commonest necessaries of life… in many of these places, it will be seen that the quantum of relief given is not measured by the necessities of the pauper, but by the sum which the Kirk Session may happen to have in hand for distribution.’

On 2nd April 1845 Duncan McNeill, Lord Advocate, stated that he sought to bring in a Bill for the ‘amendment and better administration of the laws relating to the Relief of the Poor in Scotland.’

That year, the Poor Law (Scotland) Act 1845 was passed. It created parochial boards (comprising elected members, kirk session delegates, heritors and burgh magistrates) and under their authority poorhouses were established more widely than before. Evidence within the minute books of these boards shows that they often tried to pass over responsibility for relief to a neighbouring parish from where an applicant had come. Because of this, each of the 886 separate parish administrations were protective over their boundary. Some kirk session records include illustrations of changes to boundary lines.

This was not a new occurrence under the 1845 Act. An earlier example can be found in the minutes for Mains and Strathmartine which include a map of the parish copied from John Ainslie’s map of Forfarshire from 1794.

Detail from the map of Mains and Strathmartine

NRS, Mains and Strathmartine, kirk session records, CH2/256/1 page 1

In 1724, many years before this illustration was made, a portion of the parish of Falkirk was disjoined from Falkirk and annexed to Slamannan. The inhabitants of this disjoined portion were some four miles distant from Falkirk parish kirk and had to ford a river crossing that was often impassable, but they were only one mile distant from Slamannan parish kirk. This change was much to the Reverend William Hastie’s irritation, largely because his stipend would not be increased despite his having to care for another sixty-four families. He recorded that:

‘[…] this I am persuaded of that I stand under no personal relation to these people for I was never called by them nor desired of them for though I perform duty among them as a minister yet I am only called and ordained for the people of Slamanan. I do the duty of a minister to the annexed only to preserve my ministry.’ (NRS, Slamanan kirk session minutes, CH2/331/3 page 327)

The passing of the 1845 Act helped to promote the divisions between the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor; only the ‘disabled’ and ‘destitute’ could claim relief and the ‘able-bodied poor’ were denied assistance except in exceptional situations.

Sir Henry Moncrieff, a Scottish Minister, stated that the able-bodied were ‘only assisted when they are laid aside from work by sickness or accidentall causes… they receive at that time, such assistance as their immediate necessities demand, for the limited period when they are in the situation… but when the cause… ceases to operate, the parish assistance is withdrawn.’

Outside of the church, local philanthropists, charities and mutual-aid associations were established or expanded to augment the aid given by the church. This, alongside, gradual improvements to housing, working conditions and opportunities available to the working classes towards the end of the nineteenth century slowly brought about change to how those needing extra help would be supported.

The Local Government (Scotland) Act 1929 abolished parish councils. From this time the poor law authorities served on county councils, large burghs and cities through Departments of Public Assistance (or Public Welfare), using a broadly similar system to that of their predecessors. In 1948 the poor law was completely abolished and almost entirely replaced by the National Insurance Act of 1948 and ‘social security’.

For more information about the kirk session records please see our online guide.