On the 30th July 1854, the Kinnoull session clerk recorded the annulment of marriage of Euphemia Chalmers Gray (1828 – 1897). Born in Perthshire, ‘Effie’, as she was known to friends and family, had married one of the most influential figures of the nineteenth century; the art critic and artist, John Ruskin (1819 - 1900). Using the newly released kirk session minutes, we can shed light on the marriage of Ruskin and Gray and consider how their separation and the subsequent annulment of their marriage scandalised Victorian society and had lifetime implications for Effie.

Euphemia Chalmers Gray was born on 7th May 1828 to George Gray (1798-1877) and Sophia Margaret Jameson (1808-1894), daughter of the Sheriff Substitute of Fife. Effie was born in the family’s Italian-style villa Bowerswell House, Kinoull Perth, which had previously been owned by Ruskin’s grandfather. The Gray and Ruskin families were prominent in the local area and knew each other well. Ruskin first met Effie in 1840, when she was aged 12 (he was 22) and, as a child, she often stayed with the Ruskin family at their London home in Denmark Hill.

Birth and baptism record of Euphemia Chalmers Gray, 1828.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland (NRS), Old Parish Registers of Births, 1828, 369/30 page 96

In her youth Effie was considered a great beauty and enjoyed the attention of a line of suitors. She had previously declined Ruskin’s marriage proposal but possibly owing to family financial woes (George Gray had speculated heavily in the railways and had not yet seen a return on his investment), Effie accepted his offer. At the ages of 29 and 19 respectively, Ruskin and Gray were married in the lounge at Bowerswell on 10th April 1848. Conspicuous by their absence at the ceremony were Ruskin’s parents, John James Ruskin, a Scottish wine and sherry merchant and his mother Margaret Cock.

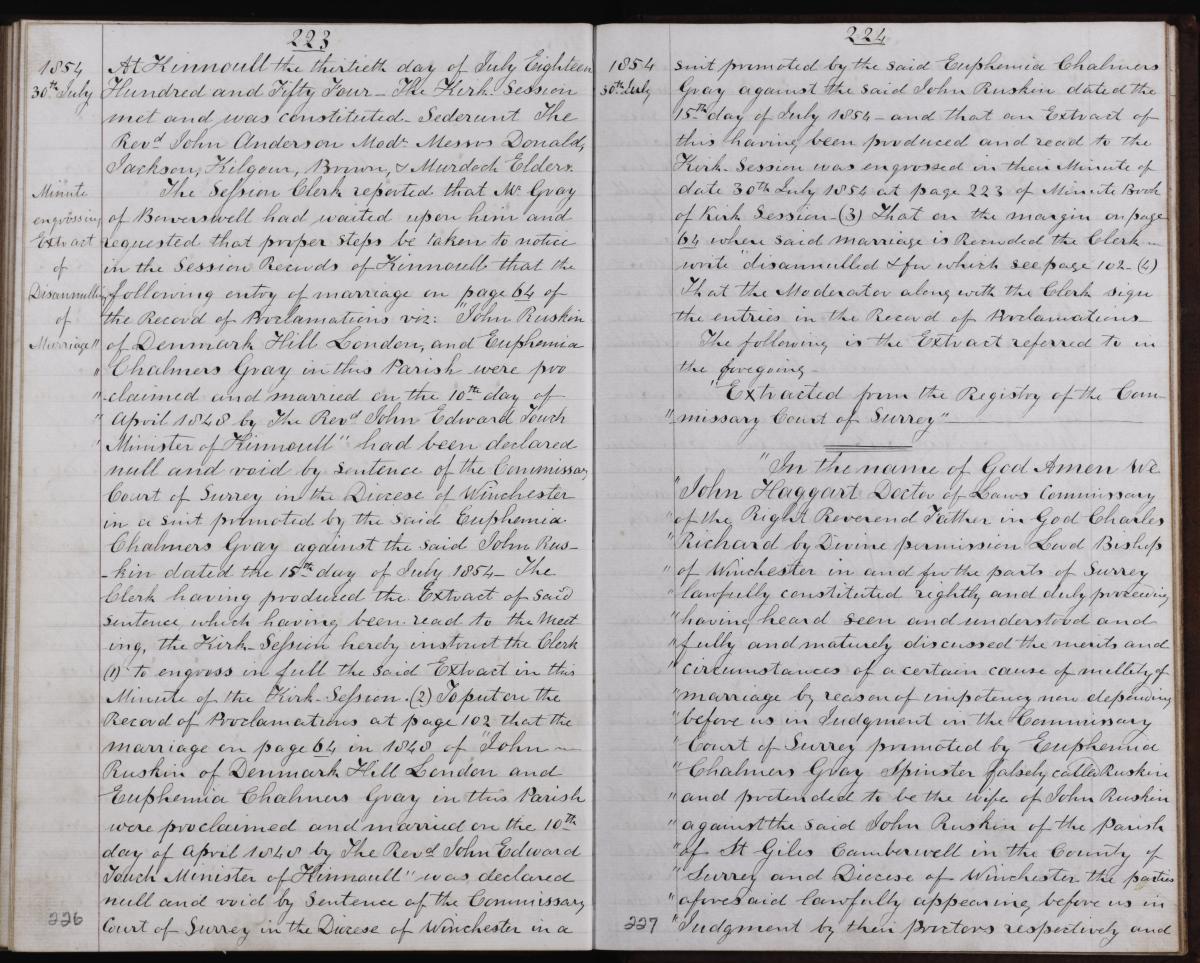

The proclamation and ‘disannullment’ of John Ruskin and Euphemia Chalmers Gray’s marriage.

Crown copyright, NRS, Old Parish Registers of Proclamations, 1854, 369/30 page 492

The newly married couple honeymooned in the Highlands and spent their wedding night at an inn in Blair Atholl, Perthshire. The marriage was not consummated that night and would remain unconsummated for the duration of their time together. Why this was the case has been the subject of much speculation; possible explanations have ranged from Effie’s mental health to Ruskin’s hatred of children. In those first days of marriage, an anxious Effie expressed concern about her family’s financial plight and Ruskin may have felt misled by Effie and her reasons for marrying him. His wife had no dowry and Ruskin’s family had paid off some of George Gray’s existing debts before the wedding ceremony.

Ruskin certainly sought legal advice on how to legally separate from Effie in the early years of their marriage. Despite marrying in Scotland, Ruskin and Gray spent most of their time together in London and travelling in Europe.

At that time, it was very difficult and expensive to obtain a divorce in England, which was usually by way of a Private Act of Parliament. The husband was often the initiator of a full divorce bill and it could only be granted for adultery (this changed slightly after 1857 with the Matrimonial Causes Act, 1857). This bill was only passed after a separation was granted by an ecclesiastical court and, usually, criminal proceeding against the wife’s lover to recoup damages.

Between 1700 and 1857, only 314 such Parliamentary divorces were successful in England. This route would certainly cause a scandal by being reported in the national newspapers and defamation of character of both parties. Ruskin was not willing to risk his position as a leading art critic and social and political thinker of the day therefore another method of separation was pursued. The consequences for Effie of a divorce would be even more damaging, resulting in a ruined reputation and virtually non-existent prospects of remarriage.

An alternative was to divorce in Scotland. In mid-nineteenth century Scotland the divorce laws were simpler, and often English couples would temporarily live in Scotland for 40 days to qualify to proceed with the action through the Court of Session. This was a small price to pay, as the cost of a Scottish divorce would not usually exceed £20 and take a matter of months, compared to the £150 cost and duration of three years of the English procedure. With both Ruskin and Gray having strong links to Scotland this, on the surface, could have proved a more attractive option for the unhappy couple. Notably in Scotland, the divorce petitions were commonly pursued by the wife, but the stigma attached to divorce was still present for both parties. This may have prevented Ruskin from encouraging Effie to apply for a Scottish divorce and to seek another method of ending a marriage that had ultimately proved unsatisfactory to both parties.

As discussed, a legal separation was possible within the English ecclesiastical courts. A legal separation was of limited value; both parties remained tied to one another and were unable to remarry. However, where a marriage was not legally valid, the ecclesiastical court could grant annulment. This declared that the marriage had never taken place and allowed both parties free to marry again. The grounds for annulment were few and included: incest, bigamy, under-age marriage without approval, kidnap, and non-consummation due to impotency or mental or physical incapacity.

The couple, having not consummated the duration of their six-year marriage, may have decided this was the least damaging way to permanently separate. The annulment took place in England, but as the now void marriage had taken place in Scotland, the annulment was noted in the Kinnoull kirk session minutes of 30th July 1854. Clerk William Murdoch, declared that the Ruskin marriage was:

‘..declared null and void by sentence of the Commissary Court of Surrey in the Diocese of Winchester in a suit promoted by the Said Euphemia Chalmers Gray against the said John Ruskin dated the 15th day of July 1854.’

The declaration of the Commissary Court of Surrey that the Ruskin’s marriage is ‘null and void’ is recorded in Kinnoull kirk session minutes of 1854.

NRS, CH2/948/7 page 223

Reading the minutes, it is interesting to note that the clerk stated that Effie ‘pretended to be the wife’ of Ruskin: ‘Euphemia Chalmers Gray Spinster falsely called Ruskin and pretended to be the wife of John Ruskin against the said John Ruskin significant’ (NRS, CH2/948/7 page 224). It was Effie’s father, George Gray who requested that the annulment was recorded in the minutes and previously gave a disposition to the Commissary Court, supporting his daughter’s claim.

The proceedings took place at the Commissary Court of St. Saviour’s Church, in south London which had jurisdiction over the Ruskin’s residence at that time in Herne Hill. Effie and Ruskin had given their dispositions to the court on the state of their marriage. Ruskin’s disposition included his dislike of children and a mutual agreement to non-consummation for a term of six years, to allow him to fulfil travel and work commitments. Both parties faced the humiliating experience of being physically examined by two doctors to substantiate their claims of non-consummation. Effie was found to show ‘signs of virginity’; however Ruskin had not appeared at court, and was not examined.

Despite Ruskin’s non-appearance, the court took three months to declare their sentence, and on the 15th July 1854, Gray and Ruskin were free of each other. The aristocratic social circles in which the former couple had moved relished the news of the failed marriage and gossip was passed on at dinner parties. Both Gray and Ruskin remained tainted by the experience.

These documents charting the beginning and end of one of the most famous marriages of the mid-nineteenth century, also shed light on the formidable social and legal obstacles thrown up against those seeking to end unhappy marriages. It was only thanks to the wealth and status of the couple that they were able to completely sever ties with one another. Whilst now free to pursue their lives apart, this had come at considerable cost, especially for Effie.

By 1854, Effie was willing to proceed with the intrusive and humiliating ecclesiastical court case and endure the scandal of having a marriage annulled, as she had fallen in love with the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais. Millais was Ruskin’s protégé and he had championed and defended the Pre-Raphaelite group in the newspapers of the day. Effie and Millais had formed a close friendship during her sitting for portraits and a painting expedition by all three to Scotland. This relationship may have been the design of Ruskin, in the hope that Effie would consent to pursue the annulment petition to be free to wed Millais. Millais and Effie married a year after the annulment at the Gray’s family home of Bowerswell, where she had previously married Ruskin.

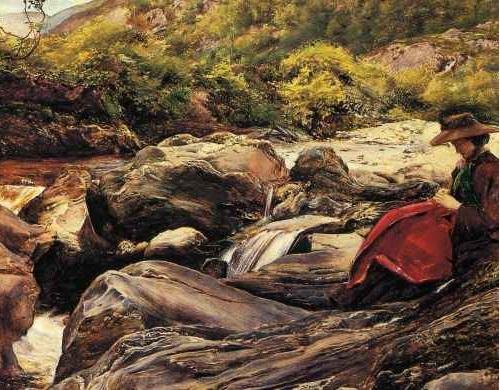

Waterfall at Glenfinlas by Sir John Everett Millais, Bt, 1853.

Painted during the Scottish painting expedition, the Ruskin's were joined by Millais who painted Effie several times during the trip.

Image credit: WikiCommons/ Delaware Art Museum

Effie’s second marriage endured, and she went on to have eight children with Millais. Nevertheless, the annulment of her first marriage cast a long shadow and she felt excluded from the circles in which she moved. This social isolation proved long-lasting. Before the annulment, Effie had been a guest of Queen Victoria on several occasions but it was not until 1896, then a widow, that she was invited again to dine at the Royal Court. Sadly, Effie’s rehabilitation into society was short-lived; a year later she died at the age of 69 at her home in Perth and buried in Kinnoull churchyard.

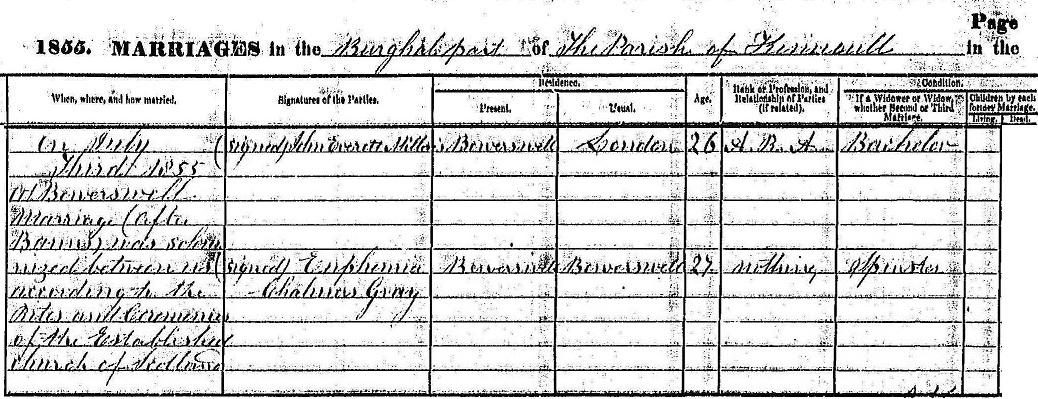

Marriage certificate of John Everett Millais and Euphemia Chalmers Gray on 3rd July 1855 (over 2 pages).

Crown copyright, NRS, Statutory Register of Marriages, 1855, 369/1 page 6

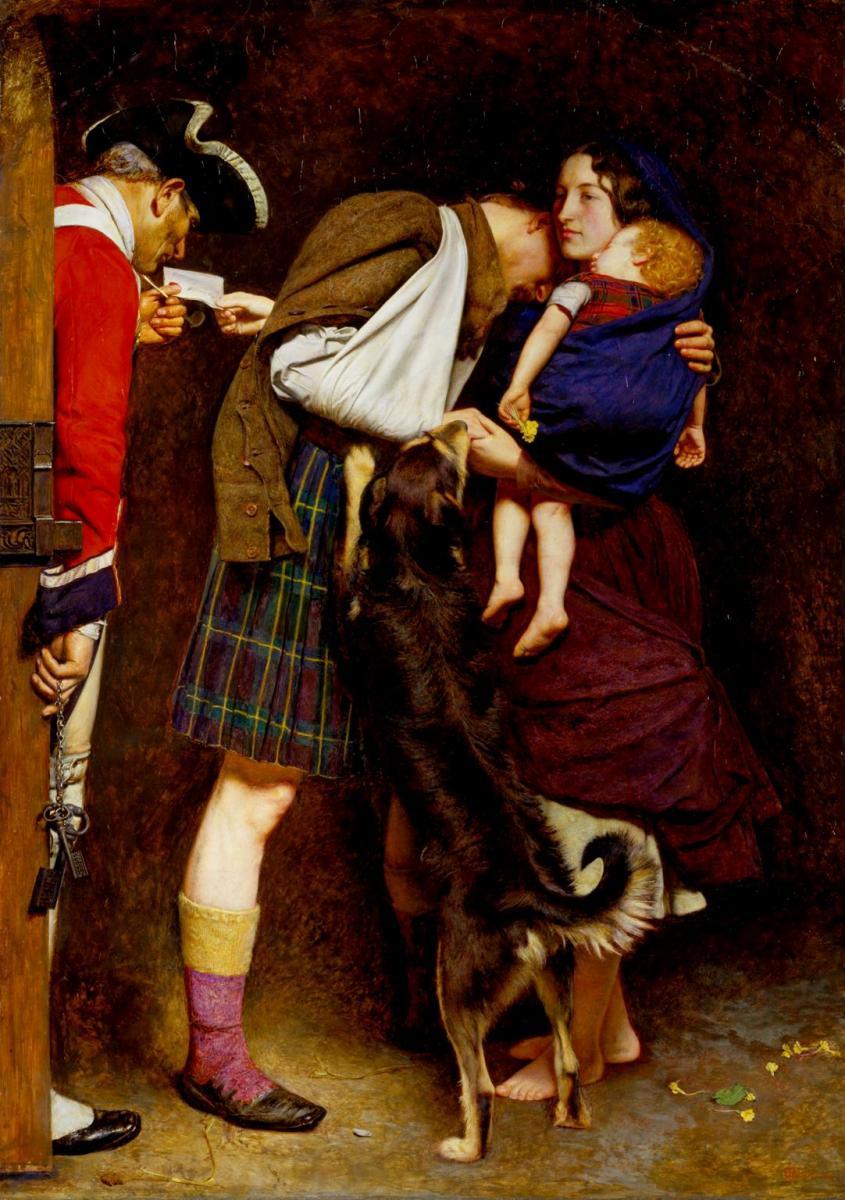

The Order of Release 1746, by Sir John Everett Millais, Bt, 1852-3.

Effie is depicted here as a Highland wife, handing an order of release for her imprisoned husband during the Jacobite Risings. It was the first painting Effie sat for Millais.

Credit: © Tate. Reproduced under Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported).

You are able to search the kirk session minutes for free with your Scotland's People account. To access these records visit our Virtual Volumes page.