The nineteenth century saw the proliferation of mining villages across Scotland, and this is reflected in the valuation rolls. One example is Oakbank, formed in 1864 as a working village for the local shale oil works. The Oakbank Oil Company ran the village in a paternalistic manner by building houses and providing local amenities for the workers and their families. In 1868, Oakbank consisted of two two-story blocks with six two-room houses on each level and one single story row of seven two-bed homes, according to the Scottish Shale website. A number of temporary homes also existed, probably to house those constructing the oil works. A report in 1914 describes the houses:

‘There are some 165 houses in Oakbank… in rows, built of brick and consist of room and kitchen, or kitchen and attic… All these houses have coal cellars and there are wash-houses for every 4 residents. The water is got from standpipes…a few houses have gardens.’ (Theodore K. Irvine, 'Report on the Housing Conditions in the Scottish Shale Field', 1914)

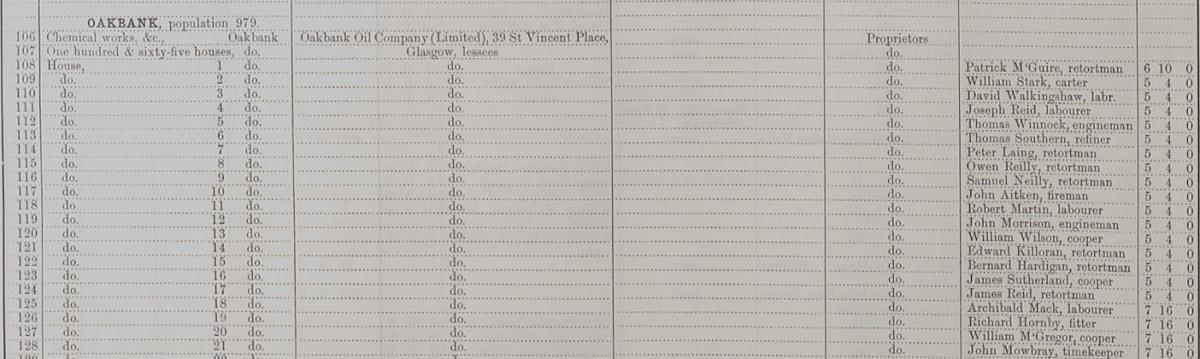

The houses, completed in 1890, varied in rental value from £3. 5 shillings to £7. 16 shillings, although the home of James Reid, the manager of the mine, at number 165 Oakbank was rated at the princely sum of £15.

Only one woman is listed in the 1895 valuation rolls, Mrs Euphemia Sandilands at 64 Oakbank. In the 1891 census she was living at that address with her husband Walter, but in 1894 he died at Midlothian Asylum, aged 37. The mining company allowed his widow to stay in her home, and in December 1895 Euphemia, whose maiden name was Kerr, married another miner, a widower.

Detail from a valuation roll listing the proprietors and tenants at Oakbank, 1895

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, VR108/26/156

Although the shale mine was the centre of the village, there were also various forms of entertainment at different dates: a tennis club, a Burns Club, Oakbank Women's Rural Institute, a Co-Operative shop, golf club, football pitch and bowling green. A school opened in 1901.

The homes in the village not only housed miners who worked in the nearby mines, but many other men in occupations associated with the mine works, such as firemen, retortmen, timekeepers, watchmen, coopers, labourers and stillmen.

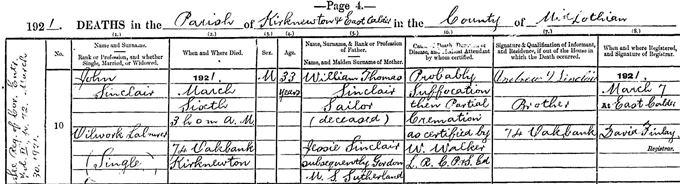

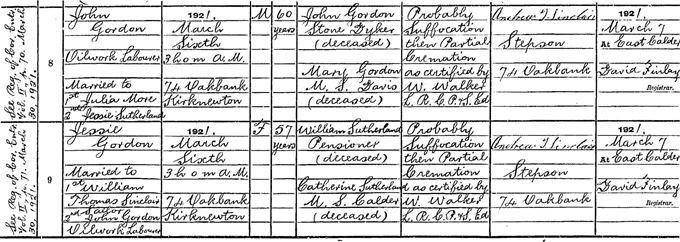

A tragedy occurred on 6 March 1921 when a fire broke out in the centre house of Oakbank Row around 3 am. The 'Dundee Courier' reported that people quickly evacuated their homes and tried desperately to save their belongings, but the fire quickly took hold. The hydrants in the village proved inadequate and by the time the Edinburgh fire brigade arrived some buildings could not be saved. Twelve houses were destroyed and 57 people were left homeless. There were three fatalities: John Gordon, an oilwork labourer aged 60, his wife Jessie Gordon aged 57, and John Sinclair, an oilwork labourer aged 33; the son of Mrs Gordon by her first marriage. It was reported that the family had lived on the upper floor of the centre house but were found dead on the ground floor, huddled together under debris, overcome by the smoke of the fire.

Death entry of John Sinclair, 1921

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Statutory Death Register, 690/10

Death entires of John and Jessie Gordon, 1921

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Statutory Death Register, 690/8

Following the decline of the shale mining industry the Oakbank houses were gradually abandoned and demolition started in the 1950’s. The last home was demolished in 1984.

For more information about these records and how they could help with your research please see our guides on valuation rolls and statutory registers.