150 years ago 131 Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow, was the scene of chilling misdeeds. This was the house of Dr Edward William Pritchard (1825-1865) the infamous poisoner and last man to be hanged publicly in Glasgow. In early 1865 two other inhabitants met their deaths at the property: Dr Pritchard’s own wife and his mother-in-law. The 1865 valuation roll eerily describes the house as empty with no occupiers. At the time the roll was compiled both women had been murdered and Dr Pritchard himself was in the North Prison, Glasgow, awaiting trial.

Using antimony and aconite, Edward poisoned his wife Mary Jane, under the guise of medical treatment, all the while posturing as her loving husband. Her mother, Jane Taylor, came to stay with the Pritchards from 10 February in order to nurse her daughter back to health, but was also to die at the hands died of the poisoner on 25 February. Mrs Pritchard’s suffering was to last until the 17 March.

Using his medical knowledge and drugs bought on account at local apothecaries, Dr Pritchard had administered the poisons to the women in the form of medicine and food – including tapioca, cheese and egg-flip. Following each death he falsely certified the causes of death – Mrs Taylor supposedly died of paralysis and apoplexy and Mrs Pritchard of gastric fever.

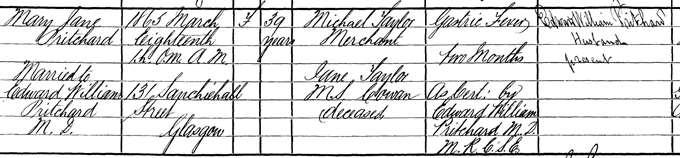

The death entry of Mary Jane Pritchard

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Statutory Death Register, 644/6 156

Falsified medical reports were a factor in his conviction. On 7 July following a five day trial at the High Court of Justiciary in Edinburgh, he was found guilty on both charges and sentenced to death. The court had found much of the evidence to be circumstantial: Dr Pritchard was the only person with the means, motive and opportunity to commit the murders but had never been caught actually administering the poisons. However, the fact he had signed both the death certificates and sworn medical declarations before the Sheriff of Lanarkshire which were proven to be untrue by post-mortem examination, amounted to a guilty verdict. Pritchard’s defence that he thought his wife had died from gastric fever was demolished by the Solicitor General: “nobody could have thought it was gastric fever. Nothing of gastric fever in it”.

This story illustrates the function of the Register of Corrected Entries. These volumes record additional information that has come to light since a birth, death or marriage was officially registered. In the case of Mary Jane Pritchard and Jane Taylor the causes of death officially registered turned out to be false – invented by the murderous doctor as a way to conceal his crimes. The real causes of death, revealed through post-mortem inquiry during the trial were subsequently recorded in the Register of Corrected Entries.

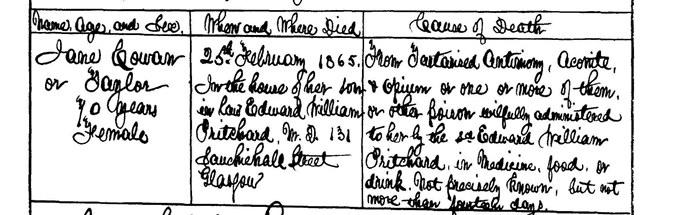

Detail from Jane Taylor's RCE

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Register of Corrected Entries, 644/06/001/133

For Jane Taylor the RCE records that she was actually killed by “tartarised antimony, aconite and opium, or one or more of them, or other poison wilfully administered by the said Edward William Pritchard, in medicine, food or drink, not precisely known, but not more than fourteen days”. Mary Jane Pritchard’s cause of death was “From antimony, and aconite, or one or other of them, or other poison, feloniously administered in food, drink and medicine, by her said husband. From December 1864 to date of death”. The original registers remain unaltered as an authentic record of information officially registered at the time – in this case a permanent record of a murderer’s lies.

Another inhabitant of the household had been the 15 year-old servant girl Mary McLeod. During the trial she reluctantly confessed that the doctor had been having a sexual relationship with her. The defence tried to suggest that Mary was behind the murders herself.

Following conviction and sentencing, Dr Pritchard wrote a damning ‘confession’ in which he said he was innocent of killing his mother-in-law and that Mary McLeod had been complicit in the murder of his wife. He said that the affair had begun in the summer of 1863, that Mary had fallen pregnant in May 1864, and that he had “produced a miscarriage”. He said that Mrs Pritchard was well aware of his relationship with the servant and that Mrs Taylor had caught them together in his consulting room.

Nine days before his execution, he made a further confession exonerating Mary McLeod. He wrote that “the sentence pronounced upon me is just; that I am guilty of [both murders] and that I can assign no motive for the conduct which actuated me, beyond a species of ‘terrible madness’ and the use of ‘ardent spirits’… and I hereby confess that I alone, not Mary McLeod, poisoned my wife in the way brought out in the evidence at my trial”.

The murders at 131 Sauchiehall Street may not have been Dr Pritchard’s first. In 1863 there was a suspicious fire at his previous address, 11 Berkeley Terrace, Glasgow, in which a 25 year old servant called Elizabeth McGrain died from “suffocation” having apparently made no efforts to get out of the burning building, perhaps because she was already dead. The fire was considered suspicious enough for the insurance company not to pay out but no criminal charge was made.

Dr Pritchard’s own life came to an end on 28 July 1865 when he was hanged to death by public executioner William Calcraft. The execution took place outside Glasgow North Prison on Glasgow Green, the last public execution in Scotland, and was said to have been attended by 100,000 onlookers.

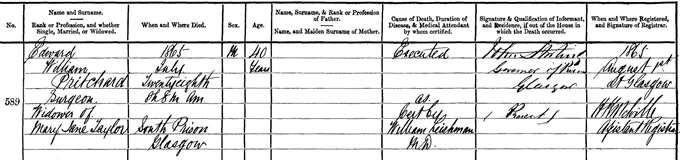

The death entry of Dr Edward Pritchard

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Statutory Register of Deaths, 644/5/589

For further information about statutory registers, please see our guide. Find out more about NRS records relating to crime and criminals.