ScotlandsPeople now includes the fascinating records of the Highland and Island Emigration Society, charting the movement of almost 5,000 Scots from the Highlands and Islands to Australia between 1852 and 1857. They emigrated in search of a better life. The name, age and residence of each emigrant and, in some cases, additional notes on their health, appearance and financial status are recorded. In 1855 Sir Charles Trevelyan announced that ‘the records [of the Society] will be deposited at the Register House in Edinburgh. They may have some social and statistical interest hereafter.’ Sir Charles had great foresight in ensuring the records would be preserved for posterity. For more information about this record set, please see our guide on the Highland and Island Emigration Society records.

The establishment of the HIES came at a time of severe destitution in Scotland. The potato blight, which had ravaged Ireland, had reached the Islands and Western Highlands of Scotland in 1846. At the same time, landlords were increasing rent and clearing their land of tenants, moving them to coastal areas and filling the land with sheep to meet demand for wool in the Lowlands of Scotland and England. The HIES aimed to relieve some of the problems in the Highlands in a way that would benefit the tenants, but also please the landlords. In contrast to the issues in Scotland, Australia sought labour to fill the numerous employment opportunities developing in the colonies.

In the summer of 1852 ‘The Sydney Herald’ issued a call for workers saying that they ‘have ample employment for many thousands of emigrants provided they be men who really give a good day’s work for a good day’s wages. We do not want idlers; neither do we want any more of that swarming class of young gentlemen who can do nothing but sit on a stool and handle a quill: Of those we have enough.’

A letter from a highlander in Australia to a friend in the Highlands of Scotland was printed by the ‘Inverness Courier’ in January 1853 emphasising the need for labour: ‘Since the Highland proprietors have turned the country into sheepwalks, and will not let the people cultivate it then it is in their duty to assist them to remove to a country where they will be comfortable. Labour! Labour! Labour! Is the constant cry here, therefore, we could take all the population of Scotland, Highland and Lowland, and still have too few’.

Canada had previously been the preferred destination for Scots emigrating independently: the passage was cheaper than to the Cape or Australia, and emigrants were welcomed with a degree of financial assistance as well as donations of food and clothing, if needed, on arrival. With the financial assistance of the HIES, Australia was now a realistic destination for many poor labourers. Under the terms of emigration, the Society selected applicants for travel and paid contributions towards assisted passages. The remaining amount was met by landowners and public subscription, however the emigrants were required to repay the Society all of the money given to them, so it could in turn be used to assist others. This assistance was a major incentive to destitute Highlanders who would not have afforded the journey on their own.

The aims of the Society

The Society, although led by the Government, had a number of influential men behind it including Sir John McNeill, Sir Thomas Murdoch and Sir Charles Trevelyan. McNeill, Chairman of the Board of Supervisors for the New Poor Law in Scotland, was aware of the difficulties Highlanders battled against daily: in 1846 he led a special inquiry into the state of the West Highlands during the potato famine, inspecting 27 of the most distressed parishes. He concluded that the only way to alleviate the problems was to remove the Highlanders from their homes and help them to emigrate. Murdoch was a civil servant, who in 1847 had been appointed as Chairman of the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners, established in 1840 to assist emigration to the colonies. By the 1850s emigration there had declined as the Australian colonies gained self-government.

Sir Charles Trevelyan, Assistant Secretary to the Treasury, was a strong believer in emigration as the cure for the highland issues. He held strict and conservative views on providing relief to the poor and believed that offering hand-outs was not an option. In January 1852 he wrote to his aunt, Miss Neave, emphasising that ‘The only immediate remedy for the present state of things in Skye is Emigration and the people will never emigrate while they are supported at home at other people’s expense…they will see the necessity of emigrating and working for their subsistence instead of living in Idleness and habitually imposing upon benevolent persons.’ (National Records of Scotland, HD4/1, p.1) Indeed, Trevelyan even sent back a cheque for £20 to a donor because it was to be used for ‘immediate relief.’ He said this type of aid was ‘making the people of the Highlands a mendicant community…The people will not hear of emigration as long as daily pounds of meal are distributed.’

Who were the HIES emigrants?

Between 1852 and 1857 the Society assisted about 5,000 men, women and children to emigrate to Australia. The Society originally sought applications from young and single men and women, however it soon became evident that Highlanders were reluctant to travel without their families. Keeping families together was seen by the supporters of HIES as one of the reasons for its success, and as the way to ensure they settled well in Australia. Revised conditions allowed whole families to travel with up to 4 children under the age of 12. Interest increased, although not everyone left Scotland gladly. Reports of the emigrants’ emotions were varied; for example, on the ship ‘Georgiana’ ‘the 23rd Psalm was sung, amidst much sobbing, … not one bitter word was spoken… They declared it, in very touching language, that they went forth trusting in God, as Abraham of old, not doubting that he was sent for God for purposes of good’. Others, boarding a ship in 1852 were said to have ‘beaming countenances [that] would rather suggest the idea that they are anticipating the pleasures of a summer excursion then that they are tearing themselves away from their fatherland.’

Applicants were chosen based on their level of destitution and the skills they could contribute in Australia. Skye was the first area selected for the project, and by the middle of April 1852 200 applications had been received. One month later, a list of 3,000 emigrants from the island had been drawn up.

The first emigrants left the Highlands in July 1852 in small open decked steamers bound for Liverpool - a journey of 400 miles. Throughout the 1850s, emigrants travelled to the English depot by train from Glasgow, or more usually by boat directly from their homes in what would have probably been their first experience of travelling on the sea. In July 1852, 951 souls were sent from the Highlands, all from the lands of Lord Macdonald of Waternish, and from the estates of Skeabost and Burnsdale. The emigrants were also later chosen from Harris, North Uist, Strathaird, Raasay, Iona, Adnamurchan and St Kilda. Emigrants from St Kilda travelled on board the Priscilla in October 1852.

Sickness and death on board ship

Dr Alfred Carr was the Surgeon Superintendent on board the ship ‘Araminta’, the third ship chartered by HIES to leave Birkenhead for Australia in June 1852. He commented on the condition of the Highlanders when they arrived at the depot in Liverpool: ‘the emigrants with scarcely an exception were in a most filthy and disgusting condition, covered with vermin, infected with itch and literally in rags; ignorant of the language and in fact more resembling brutes than human beings so far as the advantages derived from civilisation are concerned.’

Despite the hardships the emigrants had previously endured, the depot offered little comfort. Dr Carr recorded that it ‘possessed no appliances for bathing the Emigrants or of cleaning their clothes.’ The filthy accommodation and bedding helped spread disease amongst the travellers, and cause illness and death on board the ships. The ‘Araminta’ held 365 emigrants, the majority from the Scottish Highlands. They contracted measles in the filthy depot and brought it on board. Twenty seven people died during the 103-day voyage, mostly from dehydration and dysentery. An Australian investigation into the condition of the ship found that the decking had been used as a toilet, water tanks had been used to wash clothes and had become contaminated, not one barrel of flour was suitable for consumption, and livestock numbers had fallen below the recommended number.

Many other ships including ‘HMS Hercules’ carried disease on board. By the winter of 1852, the gold rush in Australia had increased the cost of passenger ships. In a bid to combat this, a hospital ship on her way to Hong Kong was chartered, costing half the price of a freight ship. Trevelyan requested that a Free Church Minister was to be placed on board, with 300 Gaelic Psalm Books and that people from each neighbourhood be kept together. ‘Hercules’ carried 756 civilian passengers to South Australia and Victoria, but it was not an easy journey. First a storm forced her to shelter in Rothesay until the new year, then small pox and typhus were discovered on board and a 3-month quarantine at Queenstown, Co. Cork was ordered. Some 56 people died, 17 orphaned children were returned to the Highlands and many others were put onto other ships, breaking families up in the process. ‘Hercules’ finally arrived in Adelaide in July 1853. Other ships’ passengers also suffered illness and death: ‘Ontario’ lost 34 of her 309 passengers (nearly all from Skye) from diarrhoea and sickness.

Emigrant families

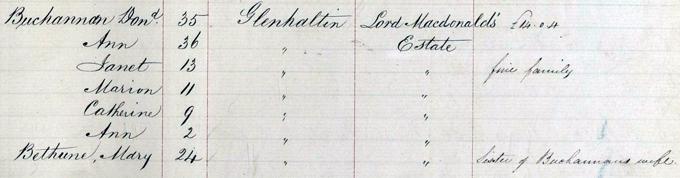

The ‘Georgiana’ left Glasgow for Port Phillip on 13 July 1852 carrying 372 emigrants under the command of Captain Robert Murray. Amongst the passengers were the Buchanan family from Inverness. Donald Buchanan worked a farm of 3 acres and had four daughters with his wife, Ann. Remarks next to their names in the emigration records state ‘fine family'. The Buchanans were given a promissory note of £14 for the journey.

1851 census entry listing the Buchanan family at their home in the parish of Snizort

National Records of Scotland, 1851 Census, 117/4/1

The Buchanan family recorded in the passenger list for the 'Georgiana'

National Records of Scotland, Highland and Island Emigration Records, HD4/5 page 10

The Buchanans and other emigrants enjoyed good accommodation and treatment on board, however the journey ended dramatically. Captain Murray reported that 16 or 18 of the crew mutinied, wanting to go to shore in search for gold. The emigrants refused to interfere or support the captain. Murray wrote in February 1853: ‘I…went forward and asked the passengers assistance, who said they were afraid of their lives, as the sailors had threatened to blow out the brains of anyone who would come to my assistance…’. Murray only had the support of his first, second and third mates and the surgeon superintendent, who armed himself. After the cook tried to free a life boat, the Captain shot him in the head, killing him. Another group of mutineers drove the mates below decks, lashed the Captain to the wheel and then escaped. On landing, the Captain noted the reluctance of his passengers to leave the ship: ‘I did not get clear of all of the emigrants till the expiring of 14 lay days, as they were very cautious and dilatory in accepting engagements.’

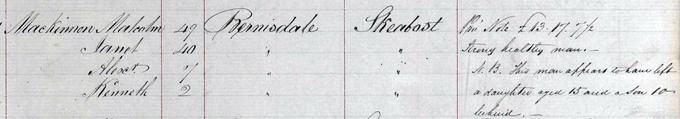

Because of the upper age limit for HIES emigrants, people sometimes gave a false age on their application. Malcolm McKinnon, from Bernisdale in Snizort did this when he travelled on board the ‘Ticonderoga’ in 1852 with his wife Janet and children Alexander and Kenneth (two of his children not listed in the census, a 15 year old daughter and 10 year old son had stayed in Scotland). His entry states that he is 49 years old, but the 1851 census records him as 55. Janet claimed to be 3 years younger in her emigration form than is noted in the census. (Census ages were usually rounded down.)

1851 census listing the McKinnon family

National Records of Scotland, 1851 census, 117/6/12

The HIES record describes Malcolm as a 'strong healthy man' and that they were given a 'promissory note' of £13 to pay the travel.

Malcolm McKinnon and his family recorded in the passenger list for the 'Ticonderoga'

National Records of Scotland, Highland and Island Emigration Records, HD4/5 page 32

The ‘Ticonderoga’ was one of four double-decked sailing ships to carry migrants from Britain to Australia in 1852. It left Liverpool 4 August 1852 carrying 795 passengers (including some 300 children under 14). By her arrival at Port Phillip in early November, 100 people had died at sea, mostly from scarlatina and typhus, and many hundred were seriously ill. The ship was not permitted to stop at Port Phillip, and was instead directed to a deserted beach, now called Ticonderoga Bay, to be quarantined. During the quarantine of 48 days, they buried another 68 bodies in the bay.

Desperately poor sanitary provisions were blamed for the high deaths and doctors were soon overwhelmed. Reports following the ship’s arrival claimed that the ship was not cleaned, and that during the voyage the bodies of the dead were bundled into mattresses in tens, and thrown overboard. ‘The Liverpool Mercury’ wrote on 21 March 1854: ‘Since the great mortality on board the ship ‘Ticonderogo’, in June 1852, which led to an inquiry, government has not despatched any vessels with emigrants save those with single decks and the results have been highly satisfactory in the great diminution of deaths at sea.’

Other ships had successful voyages with very few deaths. The ‘Allison’ left Liverpool in September 1852 for Melbourne; on the crossing 2 adults and 12 children under 14 died. Most deaths were caused by dysentery. The ‘Edward Johnstone’ arrived in Australia in September 1853, only suffering 2 deaths on the voyage, both of infants.

Over time, letters home revealed that life was not as idyllic as originally thought. Employment opportunities became more irregular, rent was high and the long journey, often filled with delays, disease and death became off-putting to potential emigrants. An example of a letter home containing negative reports was received by John Macdonald in Scardoish, Moidart, from his brother who had sailed on the ‘Araminta’ in 1852:

‘We disembarked from the Araminta on the 9th October and were 3 nights coming to Colac, which is upwards of 40 miles from Geelong. It is the prettiest spot I have seen in Australia yet. There is a large fresh water lake…the water is very bad and very scarce in some parts…It is murder to bring old people out here; nothing will do but a strong family of men who can stand fatigue and keep sober. A man with a weak family had better stay at home, as he will not get an employer to support them for him; and suppose he did get £1 a day, he could not keep them in the town. The smallest room in town is charged 15 shillings weekly.’

The outbreak of war with Russia in 1854 greatly slowed emigration and in 1857 the Society sent out its last ship with 200 aboard for Tasmania. Sir Charles Trevelyan's hope of witnessing ‘the transfer to Australia of thirty or forty thousand persons’ never came to pass.

Further reading:

David S. MacMillan, ‘Sir Charles Trevelyan and the Highland and Island Emigration Society, 1849-1859’, Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol. 49, part 3 (1963)

National Records of Scotland, Highland Emigration Society Records, HD4/1.

Contemporary newspaper reports (available through British Newspaper Archive).