Among the most useful records for genealogical research are inventories of estates, whether or not the deceased person left a will. Historically those who died without a will have been in the majority, but just because they died intestate does not mean that there will be no record of their estate and who inherited it. It is also worth bearing in mind that even people of little or no wealth can be found in the wills and testaments. Over 611,000 index entries to Scottish wills and testaments dating from 1513 to 1925 can be searched on ScotlandsPeople.

A testament is the term used to cover all the records concerning the settlement of a person’s estate. It can include a will and testament (once known as a ‘latter will and testament’), written by an individual and setting out instructions detailing what they would like to happen to their possessions after they died. This is known as a ‘testament testamentar’. However, if a person died intestate the relevant record is called a ‘testament dative’, and invariably contains an inventory of the estate submitted by the person or persons seeking to be confirmed as executor by the court and thus be empowered to wind-up the deceased’s affairs. You can learn more in our wills and testaments guide.

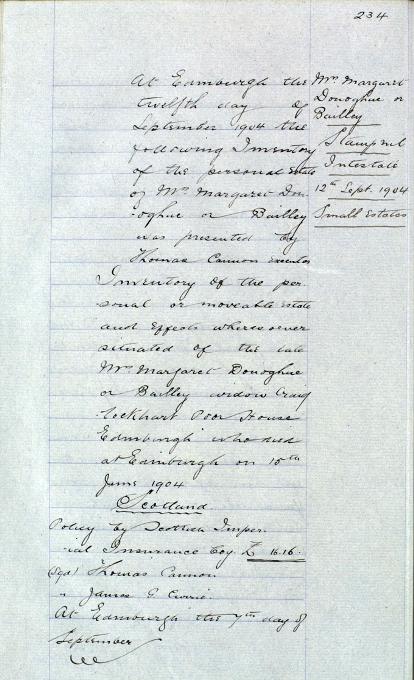

Testaments of intestate people often contain genealogical information, and the inventories themselves can also be invaluable for family history. By revealing what moveable property people owned, and the value of their estate, they provide an incomparable insight into the social and material lives of our ancestors. For example, at the low end of the social scale was Margaret Baillie or Bailley, who died in Craiglockhart Poorhouse, Edinburgh, in 1904, aged 55. Margaret, who had been a charwoman (a cleaner), was the widow of John Baillie, a street porter and appears in the poorhouse in both the 1891 and 1901 census. Margaret’s estate amounted to a life insurance policy worth £16 16 shillings, which would be about £1,400 in today’s terms. Inventories such as Margaret’s are not often extensive or exceptionally unique. They are still interesting, however, as they detail who arranged for the inventory to be presented to the court, and who had a financial interest in becoming heir to the estate, however small.

The inventory of Margaret Bailley

National Records of Scotland, Wills and Testaments, SC70/1/438/234

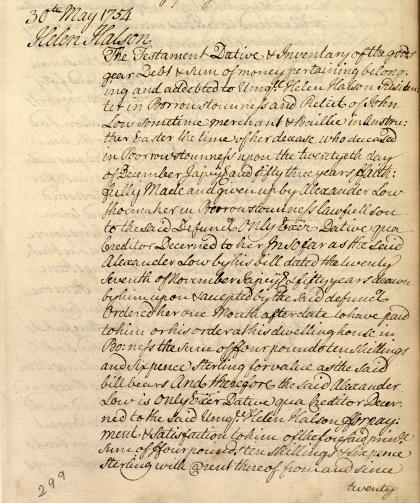

Of course, many other people had a more substantial estate. Whilst Margaret’s inventory relates to her life insurance, other wills and inventories list all types of items including, furniture, jewellery, clothes, business stock, tools and implements. Helen Halson, residenter in Borrowstounness (Bo’ness), was a prosperous widow. The wife of John Low, a merchant and Baillie in Anstruther Easter in Fife, she died on 20 December 1753. John had served as a town magistrate, next in rank to the provost, so we can assume that they lived in comfortable circumstances and this is reflected in the expensive clothes listed in her inventory. These items included: one striped gown 4s, one tartan plaid 6s, four neck napkins 2s, one sarge pettecoat [serge petticoat], one old silk apron 1s, and two white plaiden coats 1s 6d, and ‘all sterling money’.

The Inventory of Helen Halson

The National Records of Scotland, Wills and Testaments, CC8/8/115/299

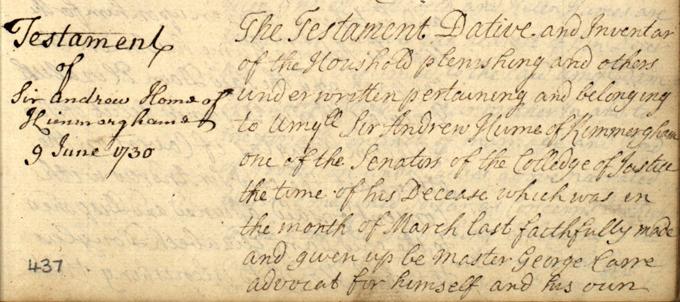

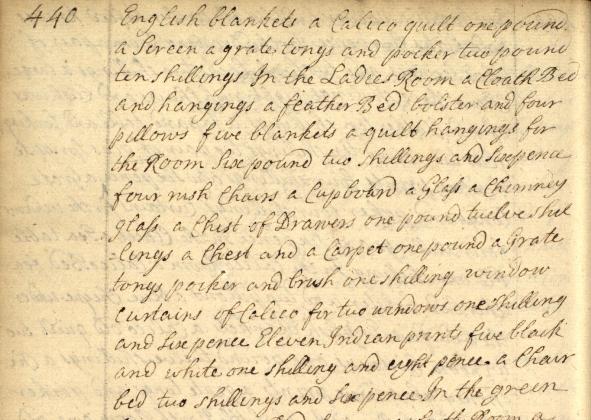

Some of the most interesting inventories list furnishings in the deceased’s dwelling house. Following the death of Sir Andrew Home in 1730, an extensive room-by-room inventory lists his ‘household plenishings’ at Kimmerghame House, Berwickshire.

Detail from the first page of Sir Andrew Home’s inventory

National Records of Scotland, CC15/5/8/437

This inventory is all the more valuable as it describes the inside of a home that no longer exists. In 1851 a new Kimmerghame House was built on the site by David Bryce in the Scottish Baronial style, and after being damaged by fire in 1938, was subsequently altered when it was rebuilt.

The property was a considerable size and comprised of colourfully named rooms: calico, blue, yellow, and green rooms, as well as a dining room, drawing room, milk house, summer house, chaplain’s room, wine cellar, granary and washing house. The full inventory also covers the contents of Sir Andrew’s lodgings in Fishers Land, Edinburgh. The detailed inventory paints a vivid picture of life in these rooms in the eighteenth century. The yellow room, for example consisted of:

‘a yellow bed, two pice [pieces] of yellow hangings, six chairs the backs the same with the bed, ane easy chair, a looking glass and gilded table, ten pound, a chimney glass, a bed bolster and four pillows, a white quilt and four blankets two pound… a grate, tongs, poker five shillings and six pence.’

The ladies room was also comfortably decorated, containing:

‘a cloath bed and hangings, a feather bed bolster and four pillows, five blankets, a quilt hanging for the room six pound two shillings and six pence, four rush chairs, a cupboard, a glass, a chimney glass, a chest of drawers one pound twelve shillings, a chest, a carpet one pound, a grate, tongs, poker and brush one shilling, window curtains of calico for two windows one shilling and six pence, eleven Indian prints five black and white one shilling and eight pence, a chair bed two shillings and six pence.’

Detail from a page of Sir Andrew Home’s inventory

National Records of Scotland, Wills and Testaments, CC15/5/8/440

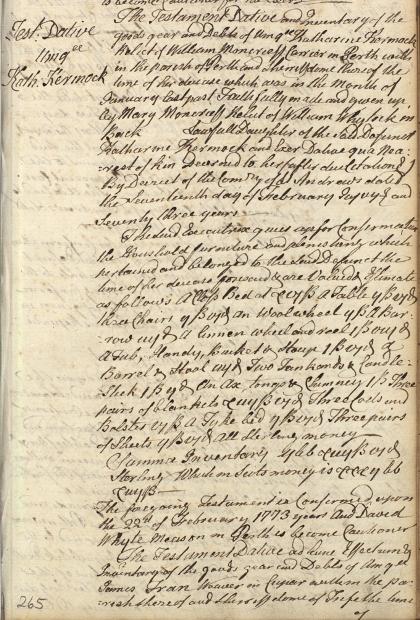

Not all homes were so comfortable. Katharine Kermock’s inventory demonstrates that she lived a simpler life with fewer home comforts. Katharine was the widow of William Moncrieff, carrier in Perth, and her inventory was drawn up following her death in January 1773. Her ‘houshold plenishing’ was fairly typical and reflected the humble circumstances for many living in Scotland in the eighteenth century. Katharine’s belongings included:

‘a closs bed [a wooden box-bed], a table, three chairs, a wool wheel, a barrow, a linen wheel and reel, a tub, handy [a wooden dish or bucket with upright handle on one side], bucket and stoup, a barrel and stool, two tankards and candlestick, an axe, tongs and chimney, three pairs of blankets… and three pairs of sheets.’

Detail from the Inventory of Katharine Kermock

National Records of Scotland, Wills and Testaments, CC20/4/23/265

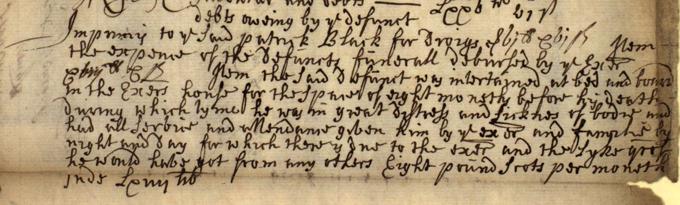

On occasion, following the death of an individual, the settlement of their estate saw relatives, friends or acquaintances come forward to request a share of the money or goods bequeathed by the deceased. Thomas Malcolm, a weaver in Perth, sought reparations following the death in 1727 of Robert Peacock, a ‘chapman traviler’ (a travelling seller of goods),who died at his home after an illness. Thomas was appointed as executor by the court, which accepted his claim that Robert had promised him money, stating he had:

‘bequeathed verbally…before…witnesses to the s[ai]d exe[cuto]r the defunct [deceased] having dyed in the exec[uto]rs house.’

He goes on to say ‘the said defunct was intertained w[i]t[h] bed and board in the Exe[cuto]rs house for the space of eight moneths before his death during which tyme he was in great distress and sicknes of the body and had all Service and attendance given him by ye exe[cuto]r and familie night and day for which there is due to the exe[cuto]r and the lyke… he would have got from any others Eight pound Scots per moneth inde lxiiij lib. [64 Scots].

Detail from the Testament of Robert Peacock of Perth, 1727

National Records of Scotland, Wills and Testaments, CC20/6/9/189