It is reckoned that between 1918 and 1921 no less than one-fifth of all Scottish land, amounting to 4 million acres, changed hands. The 1920 valuation rolls provide clear evidence of the huge transformation that affected Scottish landowners and tenants, as well as those in other parts of Britain, in the aftermath of the First World War.

Death duties and income tax rose sharply in 1918, as did local taxes and rates to help pay for local government and services. Landowners faced ever-rising costs (up to 30% of yearly income from their estates) and they tried to limit their losses by disposing of land they could afford to sell.

Some land was bought up by wealthy men in search of sporting estates, but an important trend began for tenant farmers to purchase their farms and thereby take control of their own land for the first time. From 1919 there was a steady increase in owner-occupation, and the valuation rolls provide a unique insight into the many changes that were taking place.

Sutherland Estates

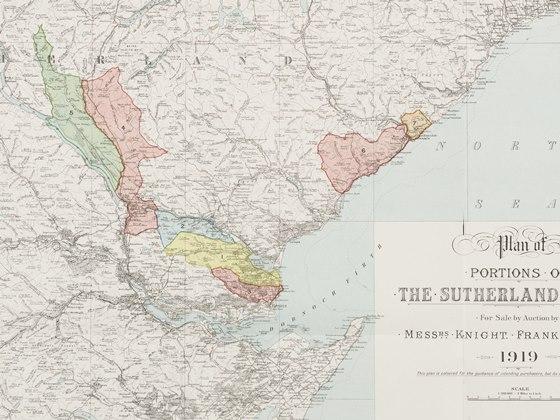

The Duke of Sutherland, one of the wealthiest landowners in Scotland, faced straitened times after the First World War. In an attempt to ease his financial burdens, he disposed of his London house, and in 1919 sold off seven parts of his estates in Sutherland, amounting to 115,000 acres. The sale included the village and harbour of Helmsdale, and the estate of Loth and West Helmsdale, as well as a belt of five adjacent estates running far inland from Dornoch on the east coast to Cambusmore, Rovie, Lairg and Shinness.

Detail from a map of ‘Portions of the Sutherland Estates', 1919.

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland RHP3353/45.

During the war the Duke of Sutherland had gifted his 12,000 acre farm of Borgie to the Board of Agriculture for the settlement of sailors and soldiers who had been on foreign service, with a good record. Soon he made over more lands to the Board, but this time it was not a gift. The Duke was forced to sell another 16,000 acre farm as he faced ever-increasing taxation, most of which was based on his land holdings. Taxes had increased costs so much that by 1916 up to 40% tax applied to all who owned land worth £8 million or more. The Duke’s lands were worth far more than that amount.

Among the post-war purchasers of these properties was William Holzapfel, who on 28 November 1919 bought the 26,500-acre sporting estate of Shinness to add to the Glenfarquhar estate in the Mearns that he had acquired around 1916. Holzapfel was an industrialist who once lived near Newcastle, but was based in London. He put Shinness on the market not long before his death in 1923.

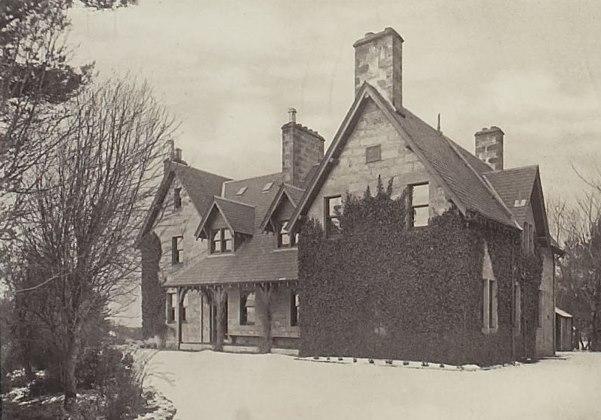

Photograph of Shinness Lodge on the Sutherland Estate

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, RHP3353/30A

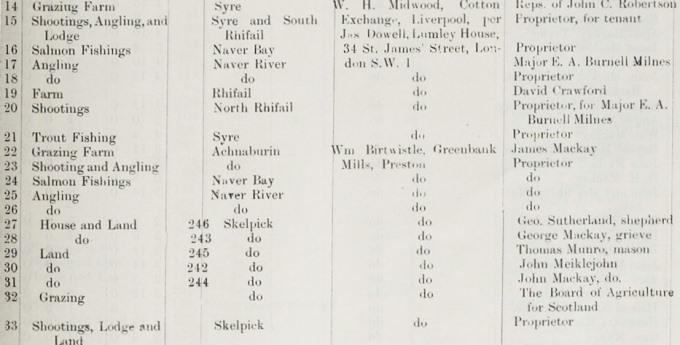

Further north the Duke of Sutherland sold large tracts of land from 1919 onwards. In 1919 he sold grazings and shootings, and angling and salmon rights along the River Naver at Sayer and Skelpick in the parish of Farr. Each property came with a lodge, and the buyers of these prized properties were respectively William H Midwood, a Liverpool cotton merchant, and William Birtwistle, a mill owner from Preston, Lancashire.

Valuation roll with the names of the new owners and properties in the parish of Farr

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, Valuation Roll, 1920, VR120/15/825

Steel-Maitland Estate, Cramond Parish, Edinburgh

Some landowners only released a small part of their estates at this period. The Steel-Maitland family, based near Stirling, also owned land in the west and north-west of Edinburgh, but it was encumbered with debt. In 1918 Sir Arthur Steel-Maitland , a Conservative MP, and his wife Lady Mary, decided to sell various properties, including the Easter and Wester Barnton Estates.

Wester Barnton was sold in 1919-20. Lady Steel-Maitland felt the sale of the land very deeply, as she explained in a letter in November 1919:

‘It is with the very greatest regret that I write to tell you that I have decided to sell Wester Barnton. As you know, it has belonged to my family for many years … It is … only because of pressing family reasons … that I have decided to take such a step. It has been a matter of great regret to both my husband and myself that we have not been able to live more at Barnton … Our relations [with the tenants] have always been so friendly … for the same reason I am letting [them] know personally before anyone else … I think it is only due to sitting tenants that if they wish, they should be allowed to purchase at the reserve price … May I say again how very sorry I am that our relations should come to an end after so many years, and I only wish it were otherwise.’

(National Records of Scotland, GD193/40/3)

One of the tenants who took advantage of buying his land at reserve price was Robert A Weddell, who paid £9,700 for his 170 acre farm, with a yearly rental value of £150. He received generous terms: £5000 was held on bond by the seller, to be paid in instalments over 10 years. In fact the 1920 roll shows that Robert and his sisters Jessie, Agnes and Jean Weddell were the new joint owners. The siblings had a long association with Wester Ingliston, as their father Alexander, a coal merchant in Leith, had also been the tenant there for over twenty years until his death in 1907.

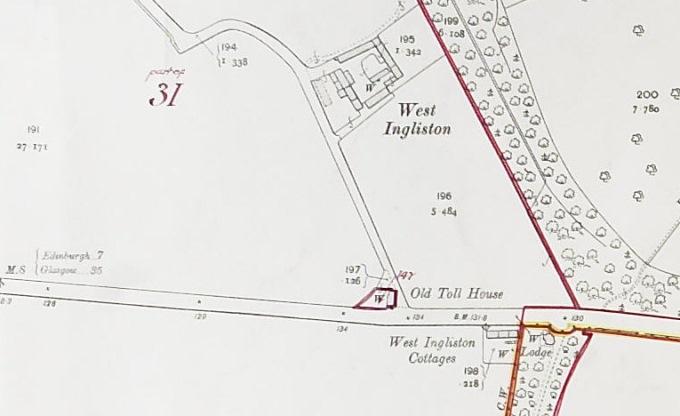

Inland Revenue Survey map of West Ingliston and other places, early 20th century

Crown copyright, National Records of Scotland, IRS119/41/1

The land at Easter Barnton consisted of ground at Whitehouse Park near Cramond Brig, and the dilapidated farm of Parkneuk, which stood where Drum Brae joins the Queensferry road near Barnton. In 1918 the Steel-Maitlands sold a little ground at Whitehouse to John Turner, who owned houses at Dowie’s Mill beside the River Almond.

In 1919 William Gray, the tenant farmer at Parkneuk, wished to give up his lease. His cousin, John Rennie Gray, had been helping manage the farm, and as his own lease of Niddrie Mains farm at Craigmillar was about to expire, in late 1919 he concluded a private deal with the Steel-Maitlands and bought the remaining Whitehouse land and Parkneuk farm for £7,500. John Gray appears as the new owner in the 1920 roll; the yearly rental of Whitehouse was valued at £177 and of Parkneuk at £170. The rolls also show that he leased nearby land at Braehead and Cammo. Changes of ownership like these were transforming the way Scotland's land was owned and managed.

For more information about these records please see our guide on valuation rolls.